Rainer Rilke and William Blake: Poetry and Reassessing Spirituality

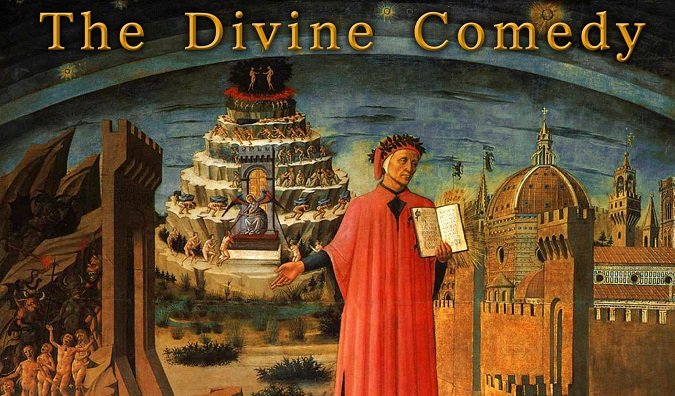

Between the divinely inspired chaos roaring across the Middle East and the continuing roll call of the horrific abuses of the organised church across Europe, and Ireland in particular, religion has a bad rap. But in a time when young people are growing up less religious than ever and once powerful organisations like the Catholic Church seem more and more irrelevant, art can offer us a window into why the phenomenon of religion held such sway in the first place. Although much of the modern artistic intelligentsia are highly critical of religion, art and faith were once much closer bedfellows.

Religious imagery has inspired everything from the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, to the Divine comedy, to the gorgeous architecture of the Shinto shrines of Japan. Two poets who I believe can offer us a new perspective in reassessing the rapture of religion are William Blake and Rainier Rilke, one a Romantic poet who believed that he received visions of God and the other a profoundly spiritual writer who believed that angels inspired and delivered many of his lyrical verses. In the poetry of these two men we find a kind of religious engagement that seems anathema to the hateful and power hungry face that many see when they gaze on the modern, organised church, or at least what remains of the crumbling remnants of its once grand architecture.

William Blake and the power of vision

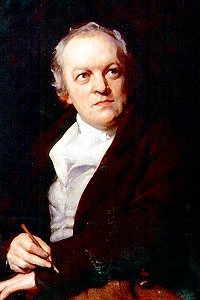

William Blake (1757-1827) was one of the most prominent poets of the English Romantic period. Although obscured by better known names from the era such as John Keats, Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley, Blake is regarded by many academics as the finest and most impactful of the Romantics. Blake was both a painter and a poet, illustrating many of his verses with gorgeous, glowing prints of chromatic angels and strange gods.

William Blake (1757-1827) was one of the most prominent poets of the English Romantic period. Although obscured by better known names from the era such as John Keats, Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley, Blake is regarded by many academics as the finest and most impactful of the Romantics. Blake was both a painter and a poet, illustrating many of his verses with gorgeous, glowing prints of chromatic angels and strange gods.

Blake’s fiery divine images were not just images culled from his vast imagination, but were representative of actual visions that came to him. From a young age Blake claimed to perceive trees “filled with angels, bright angelic wings bespangling every bough like stars” and supposedly saw God shoving his face against the four year old Blake’s window. His poetry was rapturous and mystic, embracing faith in God as an energising and ecstatic emotion. Blake professed a great dislike for the dour and sombre nature of organised religion, writing in his classic poem The Garden of Love about seeing –

“Priests in black gowns/walking their rounds/and binding with briars/my joys and desires”.

From Blake we can see a new kind of religious experience, one grounded in a personal engagement with visionary beauty as opposed to the codes, rules and strictures of organised faith.

Rilke reassessing religion

Rainer Rilke (1875-1926) was an Austro-Hungarian born poet who remains perhaps one of the most quoted and loved German language poets of all time. His work is lyrical, intense and highly mystical, freely mixing religious metaphor with mythological imagery and direct emotional language.

Rainer Rilke (1875-1926) was an Austro-Hungarian born poet who remains perhaps one of the most quoted and loved German language poets of all time. His work is lyrical, intense and highly mystical, freely mixing religious metaphor with mythological imagery and direct emotional language.

It is in his most famed work Duino Elegies that we see Rilke’s engagement with religion and spirituality most vividly. The poems were largely written in and inspired by the grand Italian castle of Duino near the Adriatic Sea. This collection of 10 poems begins with a wonderful line:

“Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the Angelic Orders?”.

This line perfectly captures the struggle of communicating our pain and hardship to something supernatural, something beyond not only our sight but often our understanding. As Rilke goes on to say –

“beauty is nothing but the beginning of terror, that we are still able to bear, and we revere it so, because it calmly disdains to destroy us.”

This line beautifully communicates the mystical concept, that Rudolf Otto referred to as, “mysterium tremendum et fascinans”, the mystery that causes us to tremble both in terror and fascination. This is a communication of the truly transcendent nature of encountering the divine, a being or beings so beyond our limited understanding that it simply destroys all preconceived notions of reality we might have, ending up simultaneously beautiful, terrifying and awe-inspiring. Rilke’s work is especially interesting because much of Rilke’s depiction of angels is inspired not by Christian imagery but by Islamic discussions about the nature of angelic orders, showing how art gives us liberty to escape dogmatic religious expression and pick and choose from a spiritual smorgasbord, allowing for a richer expression of the religious and the spiritual. [pullquote] The two tie religion to art, showing it as an overpowering, transcendent and awe-inspiring experience, free from the crushing weight of materialism, doctrine and dogma. [/pullquote]

Through both Blake and Rilke we can receive a new image of religion, in sharp contrast to that which is presented to us everywhere from Vatican City to Riyadh. The two tie religion to art, showing it as an overpowering, transcendent and awe-inspiring experience, free from the crushing weight of materialism, doctrine and dogma. Perhaps through reassessing these past ideas and appreciating these old poems we can craft new ideas about spirituality suited for the modern age.