Reading History | JRR Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings

Reading a book for the first time can have the flavor of a walk in an unknown wood – the way seems long because everything in front of you is new. Re-reading a book is like a retracing of your footsteps. Certain signposts tell you where you are and how long are left in the journey. Familiarity creates comfort. Sometimes we re-read books intentionally and other times they rear their heads in unexpected places.

I am fascinated by the ways in which books I have read at one point in life have reared their heads further on down the line. Ideas and the kernels of ideas that stay with us in adulthood reside within books that we read young. The fifth or sixth serious book you might read when a child or a young teenager has far greater sway over you – there is so much unfilled space still in your mind – than the forthieth, fiftieth, hundredth, or thousandth. In recent times, I have taken to re-reading books that I read first when I was in that formative stage of reading, from about ten and up to when I was in my late-teens, before I first went to college. It is extraordinary to see ideas that later become objects of serious study and passion first appear in protean form in the early fiction and non-fiction you are exposed to through friends, family, arriving in the form of presents or lying around the house.

As someone who went on to take a PhD in Irish history, I vividly recall the first handful of books I read where footnotes appeared – books like Tim Pat Coogan’s biography Michael Collins or Tom Hunt’s Sport and Society in Victorian Westmeath: A Case Study. I was fascinated by the very idea of footnotes; intrigued by the extra reading they provided, but I hardly understood at all the purpose and function they served. Little did I know then that they would become a key tool in work I would do later in life as a budding professional historian. Before all such books like that, there was another whose total world-building was of such a scale that it has continued to entertain, influence and cause awe in me.

Adding to the body of writing about either JRR Tolkien or his epic fantasy trilogy The Lord of the Rings is a daunting task. Finding something useful or interesting to say about a series of books that still define, in many minds, the very idea of the fantasy genre, feels like a fool’s errand. Yet, when I think about my own personal reading history and my development as a reader or a writer few others than Tolkien have done so much to influence and reverberate through my life.

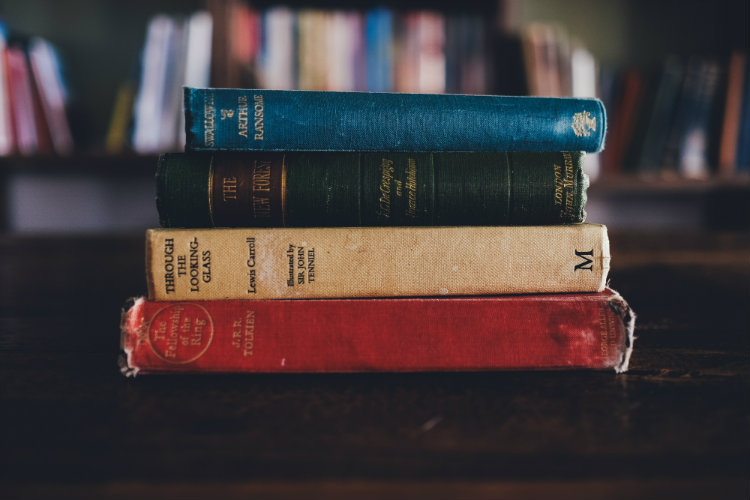

I’m not sure how or when I first encountered The Hobbit but I must have been aged around 9 or 10 when I first read it. It was superb fun – I enjoyed the riddles in the dark chapter the best. Although Andy Serkis’ performance on screen as Gollum defines the image of the creature in my mind’s eye, it was something uglier, more shapeless when I was a child. There is a sense that The Hobbit is a mere gateway to the serious business of The Lord of the Rings, which strikes me as an unfair assessment of Bilbo’s first great adventure. Seeking out The Lord of the Rings became something of a mission for me and prompted me to join our municipal library in Waterford for the first time. I remember going there, before the renovations to the central library in Lady Lane, and finding among the stacks of books a copy of the first book, The Fellowship of the Ring. It was the first book I ever loaned from a library. I was perhaps ten or eleven at the time. It took forever to read. The typeface was small, and the ideas big. It was full of maps, and weird names, and chronologies giving a history of a place that it was hard to tell if it had ever been real or not.

After finishing the first one (and renewing it at the library several times over) my cousin gave me his three volume set of The Lord of the Rings, the copies that I still have. These are the ones I normally try to re-read at least in part annually. Reading those books opened up an entire genre of fiction for me – much of it which came in the wake of Tolkien. It has cast a long, sometimes overbearing shadow and few writers of the genre have managed to step beyond the formula – exceptions being the likes of Terry Pratchett, Neil Gaiman, Ursula K Le Guin, and Alison Croggon.

But they did something else too. I read and re-read the books, and watched the film adaptations at the cinema – and later the extended versions on DVD – I went on to enjoy biographies of Tolkien and the Inklings. His work and the world of those books was firmly a part of my personal landscape but were for pleasure alone. Then I went to college.

I can remember still my astonishment that part of my reading for my First Year English classes on Beowulf, an essay by Tolkien “The Monsters and the Critics”. I would later for another class use Tolkien’s translation of Gawain and the Green Knight for an essay. It was like meeting up with an old familiar friend. Now, when I think about The Lord of the Rings, I am astonished at Tolkien’s productivity. While much of his writing as it is extant is highly fragmentary – his various translations and attempts at reworking older literature – that he left such a body of both scholarly and creative work behind in his lifetime is extraordinary.

Tolkien may well have set out to create a mythology where he thought one was absent, but he did it with a scholarly bearing that few might have matched. He invented languages, histories, genealogies, calendars, cartographies and more in the shaping of this fiction. Throughout he uses song to drive narrative forward, or to recall events of a fictive past. He is an excellent historian and scholar of his own invention – in truth his books and his methods for creating Middle Earth are good pointers to a trainee historian who might wish to draw on as many available sources as possible to bring to life the past they are writing about. Tolkien had a flair for the dramatic, and was a master storyteller, his published works point to this. It can be comforting to re-read these books, but as with a wood that was once unknown, and later becomes known, there is much to be gained from reading him still beyond the mere thrills of a battle between forces of good and evil.