The Literary Legacy of Edith Wharton

A matter of months ago, Smithsonian Magazine recognized Edith Wharton as one of the most significant Americans of all time, alongside household names such as Abraham Lincoln, Henry Ford, and Oprah. It wasn’t Wharton’s first time standing among the elite.

Born to old money during the Civil War and thrust immediately into the most fashionable circles of New York aristocracy, Wharton (née Jones) was perfectly positioned to observe—and, eventually, immortalize—a distinct and delicate social ecosystem.

New York high society in the post-war Gilded Age followed a rigid and restrictive social rule book. In a case of etiquette run amok, proper behavior, dress, manners, and discourse were dictated in infinitesimal detail. Marriages, like dinnerware, were carefully arranged. Customs were outnumbered only by taboos.

Though very much an insider, Wharton felt more like an outsider in this cramped, narrow world of formality and convention. As she entered adulthood, her resentment of Old New York’s superficial values, small-minded snobbery, and oppressive attitudes toward women grew to consume her.

In 1914, World War I would come along to destroy it all, and Edith Wharton would go down in history with the wreckage.

To say that Wharton faced obstacles on the road to becoming a novelist would be like saying she dabbled in literature (in fact, she wrote 15 novels, 7 novellas, 85 short stories, and numerous volumes of poetry and non-fiction). Her childhood and formal education were, in her words, “an intellectual desert.” Wharton managed to quench a thirsty imagination in her father’s library, studying works of history, philosophy, and poetry, but her early attempts at writing were criticized and mocked by her mother. [pullquote] Wharton managed to quench a thirsty imagination in her father’s library, studying works of history, philosophy, and poetry, but her early attempts at writing were criticized and mocked by her mother. [/pullquote]

Further discouragement came straight from the mouth of society at large. When her first engagement, at age 20, proved short-lived, local tabloids noted that “the only reason for the breaking of the engagement . . . is an alleged preponderance of intellectuality on the part of the intended bride.” Had Wharton allowed class traditions and expectations to define her, The House of Mirth and Ethan Frome would be carefully hidden at the bottom of an ornate desk drawer—if they existed at all.

Fortunately, Wharton had tenacity to spare. Her lively—and, in all likelihood, restless—mind, along with her unhappy marriage in 1885, led her to seek refuge and renewal in writing. Finally, in her thirties, she awakened the sleeping giant of her literary talent. Pen in hand, she attacked the materialism, vanity, hypocrisy, and cruelty of New York’s preposterously privileged with subtle but fierce irony. She would go on to write industriously for decades in the U.S. and abroad.

Wharton was fluent in four languages and spent much of her leisure time touring Europe and socializing with fellow writers. She counted among her friends, Henry James, André Gide, and Jean Cocteau. As her marriage crumbled, she fell in love and began an affair with Morton Fullerton, a journalist at The Times.

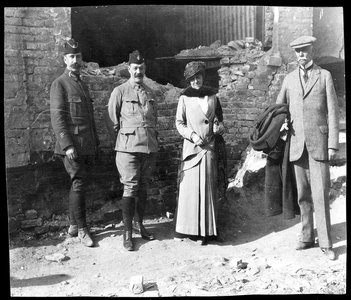

When World War I began, Wharton was living in Paris. She took an active role in fundraising and charity on behalf of the French war effort, founded a refugee hostel and a rescue committee for war victims, and even traveled to the front lines to write a series of articles for Scribner’s Magazine. In 1916, she was awarded the French Legion of Honor.

When, five years later, Wharton became the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction with 1920’s The Age of Innocence, she was stunned. According to the rules laid out by Columbia University, the prize would go to the novel that best embodied “the wholesome atmosphere of American life”—not what she had in mind when eviscerating New York’s beau monde of the 1870s. When Sinclair Lewis, a fellow finalist, wrote to congratulate her, she replied:

“When I discovered that I was being rewarded—by one of our leading Universities—for uplifting American morals, I confess I did despair.”

For Wharton, The Age of Innocence was more than an opportunity to reflect on the culture of her youth. It also presented her own detailed analysis of a society and a way of life soon to be wiped out by war and social progress. [pullquote] For Wharton, The Age of Innocence was more than an opportunity to reflect on the culture of her youth. It also presented her own detailed analysis of a society and a way of life soon to be wiped out by war and social progress. [/pullquote]Its old-fashioned sensibilities and unwavering commitment to tradition were, in many ways, its very downfall—and Wharton is sure to have savored the irony of New York’s most stylish set becoming, themselves, obsolete.

It is ironic, too, that Wharton’s literary legacy is irrevocably tied to an era and an environment she was desperate to escape. But this serves as a reminder that the written word was, and is, a form of freedom available to all those lucky enough to learn it. What makes Wharton so significant, then, is not the beauty of her writing, but the power of it—a power we salute even today.

Featured images:

huffingtonpost.com

edithwharton.com