The Open Book: Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens, AKA Mark Twain, came into the world at the heels of Halley’s Comet in 1835 and left it the same way in 1910. In his own words, “The Almighty has said, no doubt: ‘Now here are these two unaccountable freaks; they came in together, they must go out together.’”

During the time in between, Clemens crafted dozens of novels, short stories, essays, and travel narratives that made us laugh, made us care, and made us think.

It is the latter, perhaps, that shapes his legacy most tellingly. At a time when imperialism, slavery, racism, xenophobia, and sex discrimination were the norm, Clemens stood up for progress, spoke out on behalf of those without voices, and wrote against widely accepted inequalities.

It would be a shame to speak for him, so let’s hand him the reins from here on out and see where he leads us.

“Architects cannot teach nature anything.” –Europe and Elsewhere, 1923

A childhood spent on the banks of the Mississippi River in Hannibal, Missouri, led to Clemens’ ambition—and, eventually, affection—for life on a riverboat. And of all his early career moves (typesetter, printer, soldier, journalist, silver prospector), Clemens’ two short years as a steamboat pilot proved the readiest kindling to his young imagination. In Life on the Mississippi, Clemens describes his lengthy and laborious education as the “cub” or apprentice to riverboat pilot Horace Bixby: reading the Mississippi’s channels and currents, getting to know its reefs and rocks, steering through storms and the dead of night.

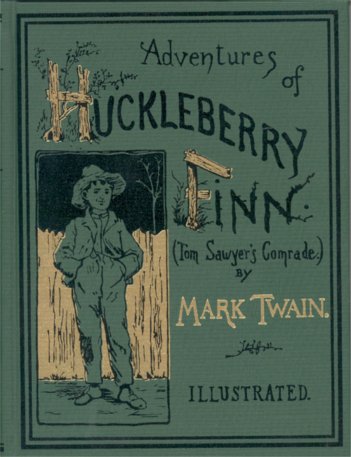

Navigating the United States’ longest river would be, of course, a significant plot point in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, when Huck and Jim pilot a raft downriver on a voyage toward freedom and encounter many of Clemens’ most memorable character creations. But the Mississippi’s impact on Clemens was more than literary; it became part of his identity when he took up the pen name “Mark Twain”—a leadsman’s call for a river depth of two fathoms (12 feet). In other words, safe waters for a steamboat.

“I take as much pride in her brains as I do in her beauty.” –In a letter to his sister, 1869

In 1867, while traveling on board the Quaker City through Europe and the Holy Land, Sam Clemens caught sight of Olivia Langdon for the first time in the form of a miniature portrait. Her brother, Charles, was a fellow passenger, and introduced the two shortly after the return voyage. On New Year’s Day, 1868, Clemens paid her a visit at home. A typical social call would have lasted 15 minutes. Clemens stayed for 12 hours. After a long courtship consisting mostly of correspondence (and one rejected proposal), they married in February 1870.

Olivia would have a profound influence on Clemens’ principles and his publications. Clemens married up in almost every conceivable way: A coal heiress raised in Upstate New York, Olivia was more educated, better connected, and far wealthier than her husband. Her highly intellectual and progressive family—abolitionists, suffragists, and reformists—served as a model for the couple’s remarkably egalitarian marriage.

Olivia was actively involved in Clemens’ writing, carefully editing his manuscripts and lectures, all while managing their growing household. In the 17 years they spent living on the edge of Hartford, Connecticut, in a house designed by Olivia, Clemens turned “Mark Twain” into a living character and cult of personality at the many dinner parties and social gatherings they hosted each week. He wrote The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Life on the Mississippi, The Prince and the Pauper, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in the third-floor billiard room/bureau amid a haze of cigar smoke.

“Always do right. This will gratify some people, and astonish the rest.” –In a note to the Young People’s Society of Greenpoint Presbyterian Church, 1901

In his best novels, short stories, and essays, Clemens combines a trademark sense of humor (he called laughter the human race’s “one really effective weapon”) with barbed social criticism. In The Gilded Age, he attacks the climate of greed, excess, and corruption that characterized the 1870s. In The Prince and the Pauper, hypocrisy and social injustice are lampooned in a comical identity swap. His masterpiece, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, follows the titular character’s struggles to shed the social attitudes of the pre-Civil War era, with Huck’s respect and affection for Jim—a slave and fellow runaway—eventually winning out over his own “ill-trained conscience”.

But Clemens did more than communicate his convictions; he acted on them. He provided university tuition to at least two young African Americans, mentored female writers, and served as vice president of the Anti-Imperialist League of New York.

His views were, in many cases, slow to evolve, but they trudged ever onward toward freedom, equality, and progress. In 1887, he wrote to a friend, describing the influence “little by little” of “life and environment” on his values. He was convinced that his extensive travels were the foundation and fount of his open-mindedness, writing in The Innocents Abroad that “travel is fatal to prejudice.”

His many enduring quotations reveal a passionate and committed liberal:

On slavery: “Our Civil War was a blot on our history, but not as great a blot as the buying and selling of Negro souls.” –Quoted by Clara Clemens Gabrilowitsch in a letter to the New York Herald Tribune, 1941

On women’s rights: “I should like to see the time come when women shall help to make the laws. I should like to see that whiplash, the ballot, in the hands of women.” –In a speech to the Hebrew Technical School for Girls, 1901

On imperialism: “I am opposed to having the eagle put its talons on any other land.” –A Pen Warmed Up in Hell, 1972

On organized religion: “If Christ were here now, there is one thing he would not be—a Christian.” –Mark Twain’s Notebook, 1935

“You can’t depend on your eyes when your imagination is out of focus.” –A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, 1889

A series of unwise investments in soon-to-fail business ventures and inventions led to Clemens’ bankruptcy in the early 1890s. Determined to pay back every penny he owed (even though he was not legally obligated to do so), he set off on a round-the-world lecture circuit. By the turn of the century, he had returned to the United States, debt-free and for good.

The legacy of Sam Clemens—and Mark Twain —is more than words and wit. It’s the idea that, together, exposure to the world and the people in it forms our most essential education, and that that education ends only when we let it. It’s a reminder that we can, and should, change our minds, freely and often. And, before all else, it’s a question—an eternal and entangled and elementary question of our humanity, what it means, and what we choose to do with it.