The Revolutionary Prose of Philip Pullman

Great literature, it has been said, is that which can be revisited at any point in one’s life, continuing to challenge, offer new perspectives, and enlighten the growing reader. Apart from a certain ramble around the streets of early twentieth century Dublin on a sunny day in June, I can’t think of another book, or set of books, which continues to enlighten quite like His Dark Materials, by British novelist Philip Pullman.

An overtly anti-establishment figure, his perspectives and contributions to children’s literature are revolutionary, refusing to pander to generally constructed standards of what young boys and girls should read, and rejecting the notions of not only gendered reading, but reading based on one’s age. Having completed the books at the age of seventeen, I was shocked to learn of their classification as children’s literature, given the extent to which notions of religion, violence, and original sin were discussed. The books are essentially about the death of God! [pullquote] Having completed the books at the age of seventeen, I was shocked to learn of their classification as children’s literature, given the extent to which notions of religion, violence, and original sin were discussed. The books are essentially about the death of God! [/pullquote]

But tied up in these existential themes is a world by which my childhood self would have been encapsulated. Following the life of Lyra, a young Oxford girl living in a universe much like our own, the story unravels characters and themes that are utterly magical. Lyra and Will, two children from separate universes, form an unlikely yet beautiful friendship as they both come to terms with the philosophical and institutional issues of living in a world utterly ruled by religion. They are chased by kidnappers, held captive for experimentation, ride in zeppelins in the sky, and travel through snowy Svalbard on the backs of talking bears.

Pullman, with a grace and subtlety paralleled by none, challenges the authority of religious institutions, and their persuasive (and damaging) effects on children and adults alike. He does so with the metaphorical realignment of theological concepts such as original sin (dust), the entity of the church (the magisterium), and God himself (The Authority – a very real and tangible figure who, as it turns out, isn’t all we’ve cracked him up to be). The idea that these themes and concepts are not for children is thoroughly rejected by Pullman who refuses to underestimate the inquiry and curiosity of his young readership.

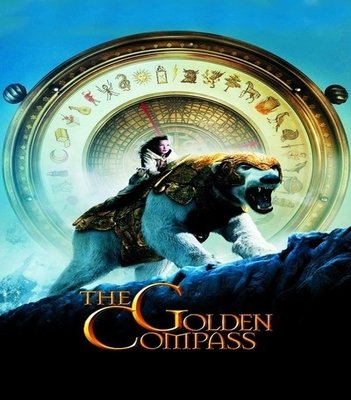

Heavy concepts for a series of children’s books certainly, but when the story is told through the means of a fantasy world of witches, daemons, armored bears, a multiverse, and two of the most charismatic protagonists (I would argue) in all of literature, it’s easy to understand how, time after time, reading after reading, His Dark Materials is one of the most accessible bodies of writing dealing with physics, theology, psychology, and philosophy. Unfortunately, these themes were utterly ignored in the film adaptation of the first book, Northern Lights, renamed The Golden Compass, and re-branded into that which Pullman sets out against – patronising stories that fail to challenge young minds (aside: the greatest pity of all regarding the film was that the cast was so outstanding, but the essence, the soul of the book, was absent).

Few authors have managed to build such an extensive universe, such accessibility of thematic material for young readers. Tolkien did it, Rowling did it, and Pullman did it. Fans now wait with giddy elation for the further expansion of his multiverse in the form of a companion novel, focusing on the lives of much loved characters from the series, entitled The Book of Dust, which promises to explore further the vast range of characters and themes.

Above all else, Pullman is an author who trusts. He trusts his readership to partake in a dialogue about ideas as complex as the universe itself, the nature of life and death, and asks them to consider questioning their own morality. He trusts children to be capable of this critical thought, and perhaps more importantly, trusts his adult readers to facilitate this space for contemplation.

“That’s the duty of the old, to be anxious on behalf of the young. And the duty of the young is to scorn the anxiety of the old.” – Pullman.

Featured images via:

aerogrammestudio.com

rogerebert.com