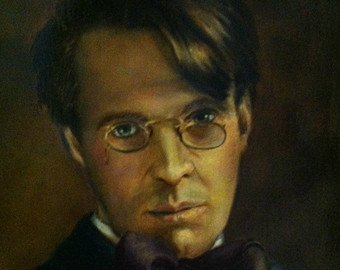

“My rhymes more than their rhyming tell” | Magic, ghosts and W.B. Yeats

As his 150th anniversary comes around, many eyes have turned to re-examining the work of the great Irish poet W. B. Yeats. But in many ways a key area of his life has been overlooked: magic. Yeats’ interest in the supernatural and the esoteric breathes through all of his work, giving his verses their transcendent, shimmering gleam.

Yeats wrote of “those images that yet/fresh images beget” in his poem Byzantium, and in many ways it was this arresting power of the image that he saw poetry and magical ceremony to have in common. Yeats thought that the poet’s ability to use words as symbols to communicate powerful imagery, to a reader that might be a hundred miles away, as being an act of magical evocation.

Yeats wrote of “those images that yet/fresh images beget” in his poem Byzantium, and in many ways it was this arresting power of the image that he saw poetry and magical ceremony to have in common. Yeats thought that the poet’s ability to use words as symbols to communicate powerful imagery, to a reader that might be a hundred miles away, as being an act of magical evocation.

In the same way that magicians and spiritualists would call up spirits and energies by the use of sacred chants and spells, the poet could conjure up powerful images and ideas from some divine, mystical realm, to enrapture their readers and give them a moment of almost divine transcendence.

Yeats dedicated himself passionately to the study of poetry and art and, alongside these things an in depth study of esoteric and magical systems. As Yeats wrote in his fantastic, entrancing, baffling and little read work A Vision:

“If I had not made magic my constant study I could not have written a single word of my Blake book nor would The Countess Kathleen have ever come to exist. The mystical life is the centre of all that I do and all that I think and all that I write.”

–Yeats’ elemental weapons and other magical tools

Yeats remains one of the most important artists of the early 20th century and, although modern students may shy away from or deride his magical fancies, the man himself saw magical thinking as central to the creation of great poetry. Art for him was not merely a hobby, or a way of wooing ladies, or gaining wealth, it was a fundamental metaphysical pursuit. Poetry was a way for Yeats to make sense of a complex and intricate cosmos and gain the comfort that so many sought in more traditional modes of religion. In the name of spiritual enlightenment Yeats had swapped the prayer books of his fellows and immersed himself instead in volumes of poetry and spell books and saw a level of spiritual connection in both.

Yeats was a committed member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, a secret society in the mould of the Rosicrucians that gained enormous popularity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Unlike other secret societies, such as the Freemasons, that would often use their mystical elements as window dressing for commercial, political and social relations, the Golden Dawn was a committed magical organisation. Middle class bohemians and intellectuals flocked to the likes of the Golden Dawn, having rejected traditional religions that seemed to them swamped with dry routine and orthodoxy, to seek a refreshing of the concept of ritual within magical studies. They yearned for the mystery, ceremony and community that came with religion, but without its stiff, musty trappings of rigid tradition and conservative social values.

Indeed sensuality was an important part of magical thinking at the time. Aleister Crowley, one of the Golden Dawn’s more (in)famous initiates, would go on to be a key member of the occult Ordo Templi Orientalis of which sex magic would play a vital part.

For Yeats, who remained a virgin until the age of 30, magic was an important way of experimenting and exploring with a sexuality and sensuality that traditional religion had derided and condemned. The rituals and symbols of the Golden Dawn, with all its fire and blood and roses and daggers, gave what could have been an airy fairy mystic spirituality a very concrete, accessible, sensual and indeed exciting grounding. In the same way that Romantic poets such as Keats had emphasised sensuality and the appeal to the senses in verse, Yeats thought the same should be done with spirituality. All the artifice and ritual of magic may seem silly but for Yeats the grounding of his spirituality in everything from crosses to Ouija boards was the same as grounding the visionary, mystical elements of your art in concrete, sensual imagery like roses, stones and swords.

Later in his life Yeats would see his poetry as actually being delivered in part from the spiritual realm. Although he was devoted to the Irish nationalist Maud Gonne (as those who have read the likes of “He wishes for the cloths of heaven” will attest) he married fellow occultist Georgie Hyde-Lees. Hyde-Lees was a creative and quite brilliant woman in her own right, but her relationship with her husband was more mutual amicability than it was the kind of consuming passion Yeats had for Maud Gonne.

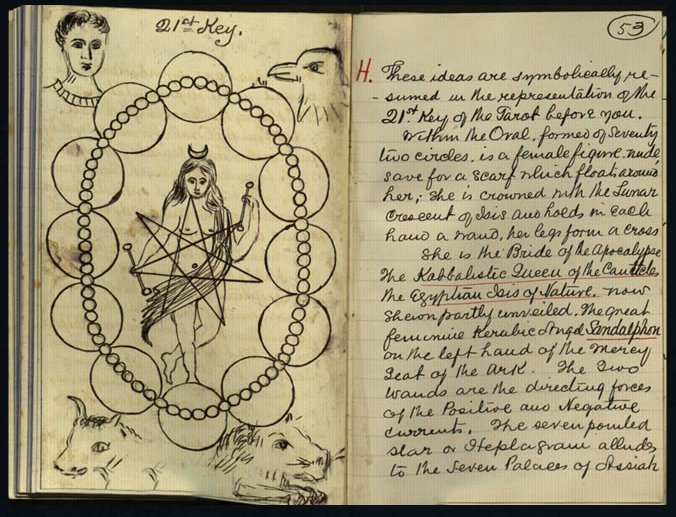

In an attempt to kindle affection in Yeats heart Hyde-Lees would appeal to his interest in spiritualism and would carry out ‘automatic writing’ sessions for her poet husband. Yeats would be astonished as Georgie was ‘possessed’ by the spirits and compelled to write words from beyond. When questioned as to their intentions the ‘spirits’ gave a response that helps us to understand the mystical poetry of Yeats later years. They claimed they had “come to bring you metaphors for poetry” and so now Yeats’ work, which had always alluded to the world of the mystic and mysterious, was now drawn directly from it.

The funny thing about the modern aversion to Yeats’ eccentric mysticism is the fact that the mystic, visionary quality of his verse is often the thing that attracts us most strongly to his work, and makes for some of his best poems. ‘The Second Coming’ and ‘Sailing to Byzantium’ are two of the most quoted poems in the English language and yet they drip with mystic, apocalyptic imagery of “sages standing in the holy fire” and “the ceremony of innocence” being drowned. Perhaps in our world so ruled by scepticism and scientific rationalism we feel a yearning for a sense of spiritual revelation and seek out this feeling of transcendence in beautiful and mystical art.

Even if it seems silly, even if it seems bizarre, one can’t deny the arresting and transcendent nature of the images that Yeats brought back from his voyages into the esoteric world. Perhaps we see in his journey of enlightenment and mystery a kind of kinship. In this world of war and famine and disease, amid our towers of concrete and slabs of asphalt, we still seek the transcendent. Whether it is in art, or religion, or even in the sciences, we continue, as Yeats would say, to look for “the uncontrollable mystery/on the bestial floor”.