Grand Tourismo | Art Through the Lens of a Smartphone

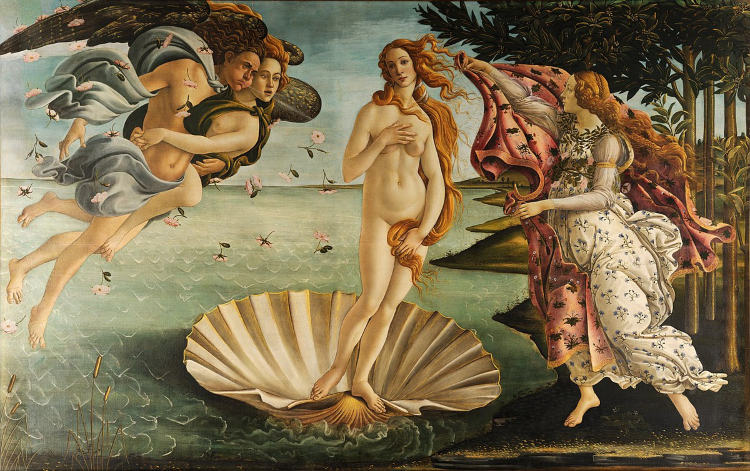

A few weeks ago I went to Florence. I visited the Uffizi Gallery. I saw Botticelli’s the Birth of Venus. I got the picture and I shared it on my Instagram story.

Like the Louvre in Paris or the MET in New York, the Uffizi attracts millions of people through its lavish walls each year (3.4 million to be exact). We were ushered in, obediently submitted to security checks and made our way to the top floor as instructed.

Entering the Eastern Corridor on the Second Floor you are instantly presented with the legacy of the Medici collectors. Rows and rows of marble busts dating from antiquity line the walls of the corridor, most of which are completely disregarded by contemporary visitors.

I was alone and while I started the art historical trek at a normal pace it was hard not to get sucked into the urgency of the scores of people who surrounded me. The forgotten sculptures in the corridor who watched us were omens of the age-old desires of humankind in these situations.

Like the Medici’s who boasted their brilliance by collecting and commissioning, we all suddenly found ourselves in the flytrap of recording our unique cultural experiences. The rooms were full of people robotically taking pictures of one image and then the next, without lifting their eyes from their HD screens to appreciate brushstrokes, scale or detail.

I was sucked in and I now have proof of my visit in the form of Huawei; enhanced photographs of original Botticellis, Raphaels and Leonardo da Vincis. Yet I have been left wondering whether I consider the experience a positive one.

Making my way up to a painting felt bizarrely akin to queueing to get on a very late and already almost full bus. You don’t want to be that person who pushes their way through, but you also don’t want to be the one who doesn’t get on.

My disillusionment isn’t one that’s directed towards the museum; undoubtedly the collection is mesmerising and, after studying Art History for four years, I am delighted that I finally saw the many masterpieces shown there.

However I was even more delighted to enter the first floor of the gallery and be presented with the temporary exhibition Grand Tourismo by Giacomo Zaganelli. Zaganelli probably found himself in my situation, or a similar one, a few years ago. The three video works on exhibition encourage the viewers to reflect on the impact of technology and social media on the experience they just had. The only disheartening thing was that I was one of few people who actually sat down to view the work.

Likening contemporary tourist behaviour to that of the Grand Tourists highlighted that the complex relationship we have with culture has been used for centuries by the consumer to elevate their status in the eyes of others. We’re no different now than we were then and perhaps this is a relief.

It’s innate within human behaviour as you can see from Zaganelli’s film “Uffizi Oggi”. At least you can’t blame millennials for this one. People have been behaving this way for centuries.

Yet the development of technology has made it a lot easier for people to record and share their journeys to enlightenment. Many galleries in recent years have chosen to respond to this by engaging with the public’s interest in taking photos.

In 2017 the National Gallery of Ireland invited Maser to respond to the Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting: Inspiration and Rivalry exhibition as part of the After Vermeer project. Maser’s response was in the form of a set—recognisable in the artist’s usual aesthetic—which people were invited to step into, to adopt the role of the muse and to contemplate the trickery of perspective in art.

I get this. It’s the role of cultural organisations to try and engage with all members of the public, to engage with contemporary popular culture, and to make their collections relevant to how people interact with the world around them today. It’s not the museum’s role to dictate how people must behave within their walls (within reason).

Or how they must consume their exhibitions. At the Uffizi, it was only when I realised that the Museum had explicitly acknowledged the change in behaviour among its visitors that I felt relieved of my anxieties about the battle for the best Botticelli instagram that had ensued on the second floor.

Of course there is a line between facilitating engagement with art and simply cheapening the idea of a gallery as a one-stop photo op. In New York pop-up galleries have opened which function as colourful backdrops to people’s instagrams.

According to Vox, last summer saw the opening of art installations worldwide, often themed around colourful foodstuffs, that apparently reflected the change that museums were going through as they began to curate exhibitions that would photograph well. The pop-up installations gathered huge crowds and undoubtedly there’s a market for these, albeit one that should not be competing with established museums and art institutions.

The insinuation that there are curators who are primarily focused on commissioning art that is fundamentally instagrammable is interesting however. We could be witnessing the birth of a new professional—one who not only curates exhibitions, but equally, your instagram feed.