Of Places | The Photography of Art Wolfe

There was snow on Yellowstone Park that day. Bushes reached out of the ground like clumps of tangled fingers and yellow winter-flowers bloomed in the grass. A grey sky hung low as if it were weighed down by the clouds, so that it blended into the whiteness of the hill. I know this because I can see it in the photograph. A simple shot of the park with a lone bighorn sheep as its focal point.

The sheep stands in the centre of the picture and looks out into the viewer’s eyes. Its horns curl in powerful arcs and the snow lies unbroken at its hooves. The pines in the background stand tall – sentries over the hillside. Snow shines on the dark hair of the sheep’s forelegs and the black of its nose. Its head is cocked in curiosity. And the dead-on camera-angle, as if he were taking a portrait, reveals that the photographer is just as curious about the sheep. But while it is the dominant figure of the photograph it is not the subject. The sheep is just one part of this picture of Yellowstone. This is not a portrait of an animal, but of a place.

Wildlife photographer Art Wolfe took that photograph in January, 2014. It was collected in his 2016 book Photographs From The Edge. In his description of it he writes: “The elements around the animal are as important as the animal itself.” His picture captures the balance between the sheep and Yellowstone, the landscape and its inhabitants. Without that balance Yellowstone Park would not have an identity. It would cease to be a place.

A place forms its identity by balancing its landscape with its inhabitants and their history and influence. In another picture included in Photographs From The Edge, a hyena dashes through shallow water with the leg of a young giraffe clenched in its maw. While Wolfe’s picture captures the violence of that scene, we only know the place (Okavango Delta, Botswana) by the animal and the description on the opposite page. In that photograph Botswana is defined by the hyena. The place appears unbalanced. It could be of anywhere.

There’s another picture from Okavango Delta that shows two lionesses stalking a herd of buffalo. Sunlight shines in the dust cloud the herd have raised. The shadows of the cats are dark against the harsh gold of the savanna’s grass. Beyond the buffalo lies a vast emptiness, hazy in the heat and dust. Here the expansiveness of Africa is clear and the animals that live in it seem smaller. They are cogs within this place, and here we can see how their teeth mesh.

Those lions killed one of the buffalo after that photograph was taken. Even that death seems small against the size of the place, like a single drumbeat in Africa’s constant rhythm. In 2013 Wolfe went to Namibia’s Ongava Game Reserve. There he got a picture of jackals eating an elephant’s corpse. It was taken at some distance and the elephant looks more like a mound of dried earth than a dead creature. The scrub is scorched and the elephant, always thought of as huge, seems small and insignificant within the savanna’s grander scheme. Jackals stand on its flank and more approach its exposed belly. This is the fate of all living creatures – death, then consumption. Wolfe captures it in a photograph that reveals it to be a part of the very dirt and dust of the savanna, just like the lions’ hunt. Our planet’s balance could not be maintained without its every element. And death is one of them.

We have places dedicated to death – graveyards and gardens, memorials and halls-of-fame. In October 2010, Wolfe went to Mexico. There he took poignant photographs of the Day of the Dead; of a woman bringing flowers to her ancestors’ tombs; a church graveyard lit by candle flames. Behind the steeple the night is a solid black. Lights glow in the bell tower and the arched doorway. On the ground the graves are pools of brightness that push back the dark. The people are silhouetted by the flames that surround their loved ones’ resting places, shadows stilled forever in a photograph. Wolfe captures the gentleness and love of that moment. These people gathered at a place that helps them make sense of the world’s puzzles. This is an image of humanity building a relationship with a place. Elsewhere, however, rather than build a connection, we have sought to dominate.

In 2013 Wolfe was in India. There he got a picture of mahouts parading their painted elephants through Allahabad’s twilight. The elephant in the foreground has its head raised and its trunk is a blur. Ornate designs of gold and red are painted on its face and legs. Two men sit on its back and steer the elephant through the gathered crowd. They have harnessed one of the most powerful creatures in nature. Then they painted their patterns on it, the symmetries and regularities that do not occur in the wild, that we imposed on it to try and make it bend to our wishes.

There are some cultures whose philosophies are centred around understanding this world and coexisting with it. They are questing for sense, not saddling the wilderness. Wolfe photographed Brazil’s Upper Xingu Indians in 1993. They live in the Amazon Basin amidst the rainforest’s sprawl and the sounds of howler monkeys and insects. They believe that the first people were animated wooden logs, and wood plays a key role in their rituals and mythology. Their most abundant resource, the fabric of their homeland, is at the centre of their mythos. They forged a cosmology out of a place on earth without destroying it or trying to force it to fit their vision, while our prevailing cultures have harnessed our world with reins of roads and then loaded its back with cities.

For centuries Western civilisation has presumed that it has something to teach these “primitives.” Wolfe’s best photographs prove that, in fact, the West has much to learn from peoples like the Xingu. They could teach us about place and our relationships with it; about how they have come to be on good terms with their homeland and how their rituals belong to it. The West’s typical working day is one long ritual repeated five times each week. It comes with its own costumes and gestures, incantations and repetitions. It is a pattern that humanity put on the world and is, in itself, not wrong. But humankind’s attempt to push the world in that direction is misguided. The Xingu tailored their ways to fit their place. We are trying to shape the world to fit our ways. A process that, as our climate crisis attests, is not working.

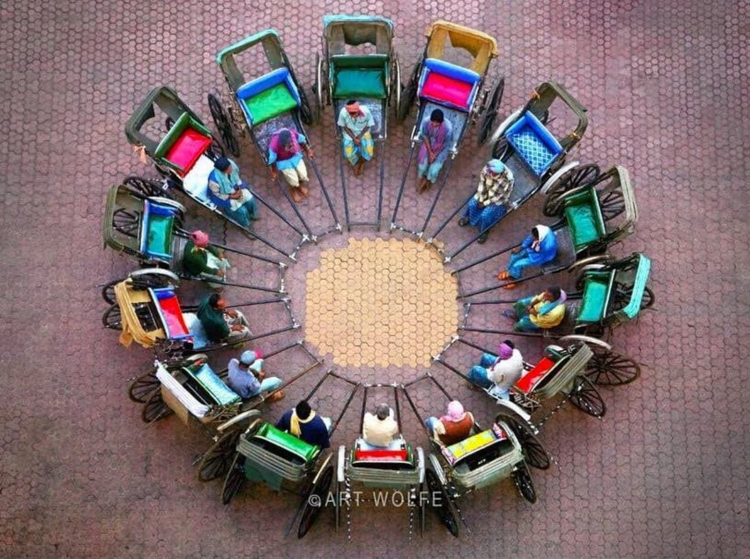

People like Wolfe have dedicated their work to giving back to the planet. His method of doing so is to show us the beauty of our world so that it is seen almost from the outside-in, allowing for a deeper view into our planet and our effects upon it. In his introduction to Photographs From The Edge, Wolfe writes: “As an artist, I try to create beautiful images, not just document the world as I have seen it.” He talks about many of his photographs in terms of “design.” Many of them are posed pictures – the scenes depicted were arranged by Wolfe for photogenic effect, rather than as representations of reality. The old axiom “fiction tells lies to tell the truth” applies to Wolfe’s work. What he has photographed in a shot such as “Rickshaw Roundup” is the process of putting patterns onto the world. Wolfe does this to create art. In a broader sense, however, it proves the point: that mankind patterns the world to establish relationships with ourselves and nature; between us and our place.

Like a great storyteller, Wolfe shows rather than tells. Indeed in Photographs From The Edge’s introduction he began: “All my life I have let my photos tell stories for me.” It is not the story of the animals he photographed, nor of their habitats. It is the epic of man’s relations with the environment. Even though his work concerns itself with the sublime, through its power I can see the toxicity of man’s relationship with nature.

Greta Thunberg is one of many standing up against this toxic relationship. Around the world there are people coming together to restore the balance between earth and humanity. In Wolfe’s photography, alongside the powerful landscapes and animals, mankind is revealed as a beauty in its own right. His pictures of Hindu rituals and Native American dancers and masked Asaro Mudmen are windows into the marvels of the human race. Our patterns are not the problem. They are the foundations of civilisation, a wonderful idea that was butchered by clumsy executioners. However when those patterns become uniform they become the problem. By forcing that uniform on a place we take away its identity. Then it ceases to be “a place,” and becomes anywhere.

Wolfe went into the world to capture beauty, and the power of his work testifies to his success. But his images can also be read as warnings; omens of a disappearing world, portraits of places that are fading away like old polaroids. In his book Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes called photography “that-has-been,” meaning that it always depicts the past. Everything that Wolfe photographed is gone, never to be repeated exactly as it was. Thunberg told us that our world is on fire. Wolfe photographed the flames.