The Painted World | Andres Serrano, Miho Museum & COCOON

Each month, HeadStuff’s Visual section brings you a taste of cities around the world. Experience the art world’s world art through our contributors from New York, Amsterdam & Kyoto.

Amsterdam

Ben Price

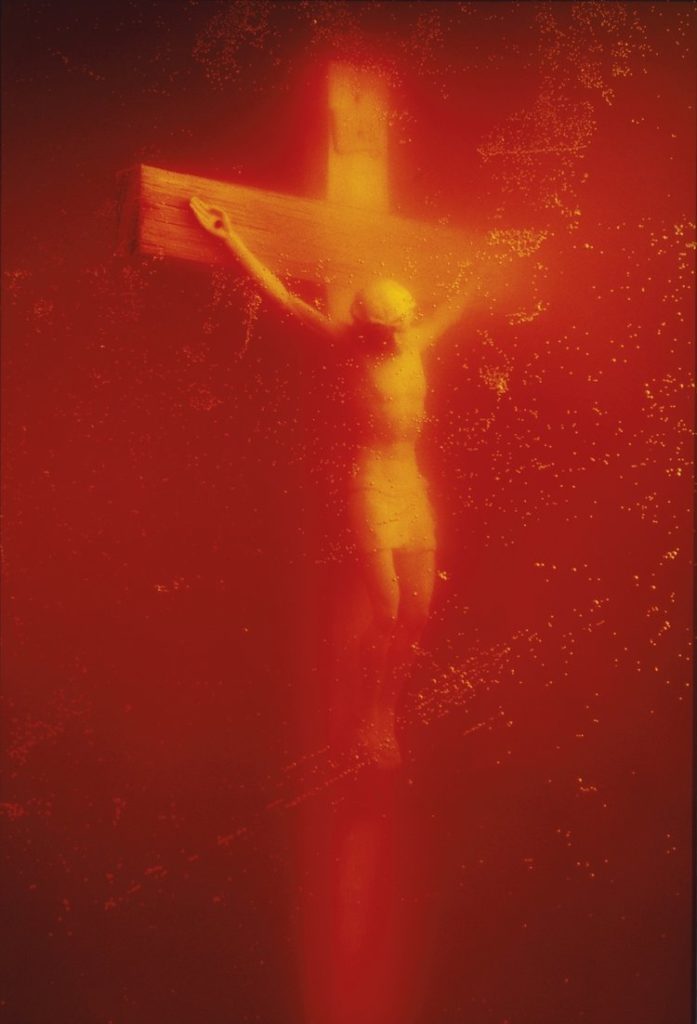

[pullquote]Are these images exploitative? Or do they empower their subjects by helping them to participate in a society from which they have been evicted?[/pullquote]Although routine, there is an uncomfortable irony in being asked to reel off your postcode before entering the new exhibition at Amsterdam’s Huis Marseille. The show – a major retrospective of the work of Andres Serrano, the photographer behind the now infamous 1987 print, Piss Christ – is a thematic survey bookended by the artist’s early and recent projects engaging with homelessness in Brussels and New York. Composed on a grand scale in a manner drawn from classical portraiture, the photographs in these series strive to bring dignity to the least fortunate in a way familiar to viewers of socially conscious 19th century artists, like Millet or Paul Henry.One portrait, the artist contends, even manages to capture its subject’s “evangelical”inner being.

However, as was the case a century and a half ago, the ethics of depicting the vulnerable must be questioned. Are these images exploitative? Or do they empower their subjects by helping them to participate in a society from which they have been evicted? Are questions like these just a patronising way of denying homeless people the agency to decide whether they are being exploited?

For Serrano’s exhibition, it’s not easy to derive clear-cut answers; but to look for them would be to miss the point.Instead, what is engaging about it is that the artist manages to secure enough of an ironic distance between his portraits and their subjects to force an awareness of the debate. To view them becomes not only an experience of establishing a personal intimacy with the subject, but also of reflexively seeing yourself debating whether that relationship is ethically sound. The style of the image may be historical, but the conceptual framing is distinctly contemporary.

Kyoto

Sinead Phelan

[pullquote]Adherents of Shumei believe that, in building architectural masterpieces in remote locations, they are restoring the Earth’s balance.[/pullquote]Last weekend I made the trek to the Miho Museum, located a quick train and lengthy bus ride outside Kyoto. As you move further and further away from Kyoto’s quaint urban sprawl, and Pachinko’s and shops are replaced with rice paddies and mountains, wondering who on earth thought to build a museum here, in the middle of nowhere, doesn’t seem out of the question.

However, its remote location is not an accident. It was built in 1996 by the Shumei Culture Foundation, an extension of the Shumei Japanese religious movement. Adherents of Shumei believe that, in building architectural masterpieces in remote locations, they are restoring the Earth’s balance. The museum is built within sight of two other structures owned by the foundation; a meditation centre and a bell tower, the latter conceived by the same architect as the museum, I.M. Pei.

The museum is tucked into the mountains, part of it despite is modern design, fitting into so seamlessly it’s as though you happen upon it, which is, of course, part of the clever design too. Once you’ve gotten your tickets you have a 7 minute walk to the museum-proper: a futuristic tunnel that leads you through and onto a bridge across the valley and to the front doors, creating a literal experience of going from darkness into light.

Inside is hardly inside , with 90% of the foyer being paneled glass, shaped like traditional Japanese temples. The actual content of the museum- antiquities from the Far- and Middle-East- are of little interest. Though it does add an all-encapsulating circle to the museum; it housing the old and it being housed by the mountain.

New York

Anna D’Alton & Deirdre McAteer

On a warm evening in May, at the offices of A Public Space in Boerum Hill, Brooklyn, the large carriage-house doors left open onto the street as a crowd began to gather to listen to artist Kate Browne, the creator of the distinctive COCOON project. The COCOON project is a series of site specific public space sculptures around the world in places marked with traumatic civic histories. Browne has based previous Cocoons in Mexico city, and Greenwood and Jackson, Mississippi. With each Cocoon, Browne spends 1–2 years in a community, recording people’s stories and memories. These audio stories are then heard inside the large-scale woven sculptures.

This particular event was the launch of a book about Browne’s most recent Cocoon in Goutte d’Or, a neighbourhood in the 18th arrondissement in Paris which has a long history as a settling point for immigrants from France’s colonies in North and West Africa. Goutte d’Or is one of the many high-rise suburbs on the outskirts of Paris which is under-resourced and dilapidated, home to large immigrant populations who in the past have protested against authorities for what is seen to be systemic discrimination against Arab and North African communities. Through text and photographs, the book gives an account of Brown’s work there, including verbatim stories from some of the neighbourhood’s residents who contributed to it. The book –and the evening of discussion which launched it–was an excellent opportunity to share insight into the Cocoon project and for Browne to share stories about its inception, the impetus behind it and her experiences in the different sites where the project has been executed.

[pullquote]You don’t get a sense of an artist visiting a place and making art out of it for their own ends.[/pullquote]The majority of the evening involved a discussion between Browne and Bob Sullivan, a writer who collaborated with her to produce the book. Photographs by Eric Etheridge documenting the Goutte d’Or project were displayed on the walls behind Browne and Sullivan, providing reference points as Browne relayed anecdotes from her experience working with the neighbourhood’s residents, interviewing people in Goutte d’Or who shared stories of immigration and their attempts to create a life for themselves whilst navigating clashes with the authorities in a heavily-policed neighbourhood.

One can’t help but be impressed by Browne; the Cocoon projects speak for themselves. You don’t get a sense of an artist visiting a place and making art out of it for their own ends; rather, she commits to spending time in these communities, to meeting people and recording their stories rather than telling their stories for them.