A Mother Brings Her Son to Be Shot, I, Dolours and the Rise of Troubles Documentaries

The conflict in Northern Ireland has provided the narrative fuel for many an Irish film in the past 30 years. Neil Jordan made Angel and The Crying Game, Jim Sheridan directed In the Name of the Father and The Boxer. On top of this, there has been the wave of post-2000 movies drawing upon The Troubles including Sunday Bloody Sunday, Fifty Dead Men Walking, Hunger, Five Minutes of Heaven, ’71 and last year’s Maze.

Moving closer to the 20th anniversary of the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, the number of films being released addressing the violence of the past and its lingering effects have risen. In the last month, we have had Massacre at Ballymurphy, I, Dolours and A Mother Brings Her Son to be Shot – three documentaries that together serve as a gripping unofficial trilogy – detailing escalating tensions between Catholics and Loyalists in the 1960s, the rise of the provisional IRA from the 70s onward and the impact the Troubles has had on those living in the North post the peace process. Why are all these films suddenly being released?

“I am asking the same question because many are interested in this story now,” says Darren O’Reilly, Derry-based politician and talking head in A Mother Brings… “We’ve had people from all over Europe and Britain coming here. Stacey Dooley was here, Ross Kemp too. We’ve had Australians, French, German filmmakers all come to North recently.”

Councillor for the Foyleside district of Derry, O’Reilly believes the uptick in movies addressing the Troubles is related to the violence which has continued in the north post-Good Friday Agreement: “We are seeing an upsurge in media asking the question ‘What was going on here?’ I think that’s because people see in the news shootings are still occurring even though it’s been portrayed around the world that now there is peace. People are asking: “Why is this still happening?’

All three documentaries touch upon what O’Reilly dubs ‘the hangover’ of the Troubles, particularly A Mother Brings… The film centres on Majella O’Donnell, a Derry mother forced by the Real IRA into bringing her son Philly – accused by the dissident republicans of being a drug dealer – to be shot in the leg. It uses that tale as a jumping off point to analyse the aftermath of the conflict. While militarised loyalist police are now of the past and sectarianist violence is less common, the Real IRA still serve in some communities as unofficial police, dishing up ‘punishment shootings’ and ‘swift justice’ to those they consider a threat to the status quo.

“This is deemed acceptable because it had happened for a long time,” says O’Reilly. “Perhaps, people are seeing this kind of behaviour still going on even with the peace process and are asking questions like: ‘Is it really peace if kids are still getting shot?’”

A Mother Brings… also explores the psychological effects the conflict and its aftermath has had on those living in the North. According to a 2015 report from the Commission for Victims and Survivors, around 213,000 adults in Northern Ireland have developed mental health difficulties linked to their experience of the Troubles, including clinical depression and PTSD. “More people have died through suicide since 1998 than throughout the whole conflict,” O’Reilly highlights.

“It is horrifying to think of the scale of damage to mental health. This also permeates down into the next generation,” says Martina McCann, Head of Communication and Engagement at the Commission for Victims and Survivors.

The recent spike in films addressing The Troubles could also be related to fighters in and victims of the conflict’s fears of speaking out until now. I, Dolours – the documentary chronicling Provisional IRA member Dolours Price’s life – derives its story from a one-on-one conversion with its subject. She spoke to journalist Ed Moloney in 2010 on the condition the interview would only be released after her death – she died in 2013. “Informers were seen as the lowest form of human life … Death was too good for them,” Price herself says in the documentary.

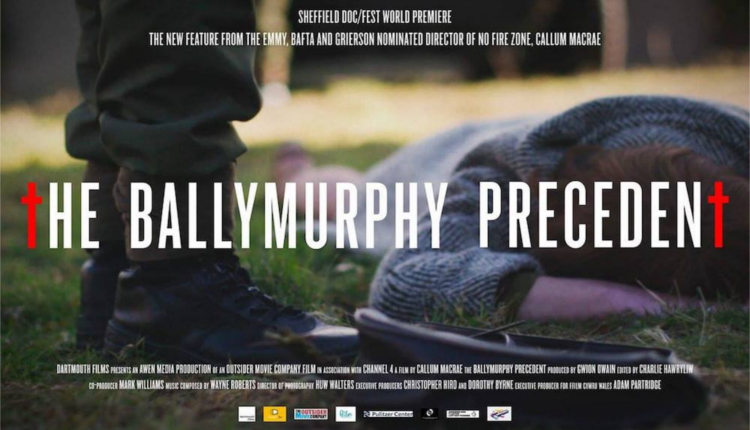

Meanwhile, Massacre at Ballymurphy (also known as The Ballymurphy Precedent) focuses on a series of incidents between August 9-11 in 1971 in which the 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment of the British Army killed eleven civilians in Ballymurphy in Belfast. The event was later dubbed Belfast’s Bloody Sunday, a reference to another killing of civilians by the same battalion in Derry a few months later.

Piecing together the killings from eye-witnesses, the documentary also explores the victims’ families trauma after the event, particularly with media at the time calling those who had died IRA affiliates. “I thought if I told anyone – a Protestant – my mummy was murdered but that she was innocent, they would say: ‘She’s only saying that. Her mummy must have been a gunwoman,’ says Briege Voyle in the documentary, daughter of the deceased Joan Connolly.

“There’s a huge culture of fear around the notion of sharing information. People are aware of how informers have been dealt with in the past. Those entrenched fears were inbred during the Troubles,” says Dr Ciara Chambers, Head of Film and Screen Media at University College Cork. “Perhaps, there is a sense that because some decades have past, people feel now might be the time for them to tell their story. Maybe these films telling forgotten stories signal a culture of change around speaking out and discussing these issues, in an attempt to heal some of the wounds of the past.”

Chambers notes that from a filmmaking perspective, the Troubles can be a tough subject to tackle in movies: “There’s a problem in that Irish politics are so complex that it’s very difficult to convey a nuanced understanding of the historical context in a film that’s ninety minutes long or less. That leads to anger as people feel their stories have been glossed over or that one side is prioritised over the other. I think this complexity scares off funders, producers or even filmmakers themselves. It’s hard to make a film that doesn’t face backlash in some way.”

Through using individual subjects and events as an entry point to detail the wide scope of The Troubles, these three documentaries managed to overcome the struggles Chambers lists, each earning critical acclaim. However, do these films addressing the past help those who lived through the conflict?

“People want acknowledgement about what happened to them and the truth to emerge. Documentaries are one mode where that can be realised,” says McCann. She argues though the Stormont House Agreement, a political accommodation between the British and Irish Governments, would help victims further in this respect. The 2014 proposal includes an information retrieval commission in which victims – with the help of intermediaries – can seek details about loved ones who had been injured or killed in the conflict from those who had committed the harm. The evidence collected under this scheme could not be used in a prosecution. Due to delays, however, the agreement is yet to be implemented.

“As you see in Massacre in Ballymurphy, many families have had to lead the pursuit of information and truth themselves. The burden of building a case surrounding the death of loved ones in any modern democracy should not fall on the victim,” says McCann.

O’Reilly also believes this wave of Troubles documentaries are a positive for victims. “My grandfather was shot and injured on Bloody Sunday. While he was alive, Channel 4 had produced a documentary on the subject. That went a long way to showing the rest of the UK what had been done,” says the politician. “For a long time, the Bloody Sunday families fought the same smear as those in Ballymurphy. The people involved in the protest or even just in the streets were labelled as gunmen, murderers and bombers around the world. Any clarification to show that people’s family members and friends were innocent needs to be said aloud.”

Continuing, O’Reilly says: “For us to move on, these stories must be told. If we don’t address them, they’ll fester. This dialogue and discussion about what happened goes a long way towards that.”