When Harry Met Darkness | Alfonso Cuaron and The Prisoner of Azkaban

There is a certain well-known secret that is whispered in the Harry Potter Universe somewhere between the general failure of Daniel Radcliffe’s recent acting career and the strange charisma that exudes from Michael Gambon’s creepy Dumbledore.

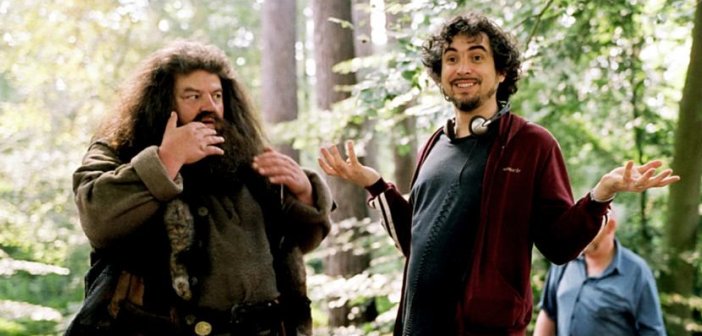

That secret proclaims, in a voice quite unlike that of your average secret, that Alfonso Cuaron was the prime mover for the cluttered beauty and overall sense of strangeness which later became so prevalent and unique to The Harry Potter Film Series. What a mouthful! A mouthful that deserves to be spat out, finally, and more than that, a mouthful which has been so poorly documented as to deserve the moniker of a secret.

The Prisoner of Azkaban, the third instalment in the highly lucrative Harry Potter Series, is ostensibly the point at which the film series established a style of its own. In this film we reach a point of maturation. We move beyond the first pair of films in the franchise, which were, undeniably, successful in their own right, and our estimation of our characters starts to build as we see them make conscious decisions to be brave, despite the cloying presence of their misgivings.

[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R69laoH02xg”]

Alfonso Cuaron has stated on countless occasions that the preceding films, and the director of those films, Chris Columbus, were integral in establishing a starting point for the world and the tone of universe. There is the sense, with that first couple in the film series, that the cast, the settings and the script were thrown together too fast and with a bit too much haphazard glee. Glee for the guaranteed money which would accompany the release of these adaptations, and glee for the general spectacle which was being created.

Columbus may have been integral in giving birth to the film, however, the subsequent evolutionary stages through which the franchise was destined to fluctuate required a different voice and a different mind. Consider the timeline in the lives of our main heroes. These films take place in their teenage years. Each year in the life of a teenager is almost like a new beginning, a different epoch in the history of the world.

Enter Cuaron, who was at that point, not in possession of the lofty reputation that he now possesses, following the highly lauded success of his space thriller, Gravity. He was, however, riding on the success of his most recent release, Spanish language, teenage epic, Y Tu Mama Tambien, which is a cauldron of emotion and sex, but at its heart the film deals with themes of maturity and immaturity. Upon initial inspection, the film strikes the casual observer as being in large contrast with the Harry Potter series. But, scale back from the immediate view of both films and we may understand something basic. What is Harry Potter but an insight into the lives of fucked up teenagers? To a certain extent, what teenager doesn’t, at some point, believe that they are fucked up?

So we see the sense of Cuaron’s position, and really, for viewers not keen on the saccharine side of the silver screen, the employment of Cuaron should have been praised, as much as Christopher Nolan’s lauded position as Director of the rebooted Batman series.

Examine the standpoint taken by Cuaron with regards to this particular iteration in the series. The characters have turned 13. Harry deals with a growing circle of relationships. He is dipped into the past, with the introduction into his life of Godfather Sirius Black and a new mentor, and friend of his Father, Remus Lupin. These more intimate relationships present new opportunities for honesty. We begin hearing the story of Harry’s youth and of his family life, which gives us a different, and more intimate, personality arc to observe. Compound that intimacy with their maturation and we find ourselves in a different world and that world is darker.

The larger politics at play within the wizarding world assure that this is so. There is a cloud hovering above Hogwarts – the impending return of dark wizard Voldemort – and the past is being replayed in memories, which had been buried, which are now digging themselves out of the ground. We get the impression that these characters are more capable of handling this kind of information with verve. After all the trio had just recently come up against Voldemort for the second time and foiled the evil wizard’s plot for the second time. What is a rumour, a memory or a new relationship in comparison to their experiences with impending death

Cuaron sees the potential for this change in tone and he executes it well. Alongside this maturation in our heroes, we also see the same kind of growth in terms of technique with better camera use, better acting and better scripting. He attests to his own personal preferences, as well as his understanding for the direction of the story;

“The funny thing is, I’m trying to serve the story, but at the same time I’m a different mind than Michael or Chris. I operate in different ways and I respond to different things and I have different flows and different urges than the two of them. I made some decisions in this film which were not just to stand out, but because I felt they were the right things in my understanding of how to serve the story.”

Cuaron uses tension well in dialogue, he supports the blooming personal lives at stake, with lines and with scenarios which were all but unthinkable beforehand. Not only this but he also succeeds in dipping Columbus’ bright, fantastic world into that darkness.

The landscape of the film, especially in the forest and the surrounding areas, has changed. The castle has many shadows, the forest is a bit more encroaching and grotesque, in the style of something Scottish, something Macbeth-ian. The overgrowth on show in certain pumpkin patches, and the dilapidation of certain shrieking shacks mirrors the landscape of Cuaron’s other films, such as Great Expectations.

In Cuaron’s film we can see the first seeds of what was to follow in the later films of David Yates. Yates did a great job of showing the wizarding world as a minority, of draping the Universe is as much shadowy secrecy as could be allowed for such a major film. We see it in his own use of isolated setting, and shadowed lighting. As such, in The Prisoner of Azkaban, while the story progresses it becomes more apparent that wizards are being, and have been, pushed to one side. The world of wizardry is becoming the minority. It is only later in the series that we find out that this has always been the case.

In the case of every minority, the places in which those who hold power are always the darker places, the unseen places. Whereas the story does not purport to this, we can begin to see it in the way in which Cuaron sets up the design and the architecture of this film.

The buildings in Diagon Alley are shabbier. The rooms have less light and they seem dingy by comparison to the grand buildings we were treated to in The Philosophers Stone and The Chamber of Secrets. There are no sweeping views of cities, but only a sweeping view of the landscapes that surround the isolated Hogwarts castle and a better understanding, with help from the Marauder’s Map, of the lesser known passages of the castle.

So whereas Cuaron’s contributions to the Harry Potter Series may be lost in the overall legacy left by these films, it seems unfair, because Cuaron, in this third iteration, carries our heroes through the difficult transition, through a difficult age. Under his directorship the series catapults into the future and leaves behind blind optimism, in favour of a darker shade of brooding, which is so attractive to the dirty secrets that reside within you and me.

Featured Image Credit