Art Encounters | Memory Matters (Hunting for Something Other than Deer)

‘Reflective perception is a circuit, in which all the elements, including the perceived object itself, hold each other in a state of mutual tension as in an electric circuit, so that no disturbance starting from the object can stop on its way and remain in the depths of the mind: it must always find its way back to the object from where it proceeds,’ – Henri Bergson, Matter and Memory.

Having moved to the country, I was put out by the thought of having no internet for an extended period. I had been in the suburbs for two decades, had thought the street lights outside – shielding us from the darkness – were part of the natural order of things, and feared the retreat into pre-lights and pre-net living moving to the country entails. The kids would freak out, chase each other around the house in a fit of Whatsapp deprivation; withdrawal even, and any downtime in front of the newly burning fire would be threatened from all directions. Plugging out of the network, for all of a week, seemed too much like the plot of a 90s David Cronenberg film.

But one of the weird things about moving home/house is that it brings with it a sudden unearthing of the past, like the dredging of a riverbed, so we confront our life in the form of objects – sometimes feted and saved for – once put away in storage. All sorts of ‘things’ come to the surface, some of which we want to just bin straightway, others that remind us of a not-too-distant past consistent with the present. In such moments we realise our former selves are not as strange, as out of time, as we thought. But we still feel kind of stupid that this judgement was made on the basis of stuff we own. A box of CDs, one of which holds three copies of Queens of the Stone Age, Songs for the Deaf (a most pernicious example of conspicuous consumption) competes with a box of DVDS, inside which is a once prized Kubrick boxset that looks in need of a new home. I remember I don’t even own a DVD player anymore.

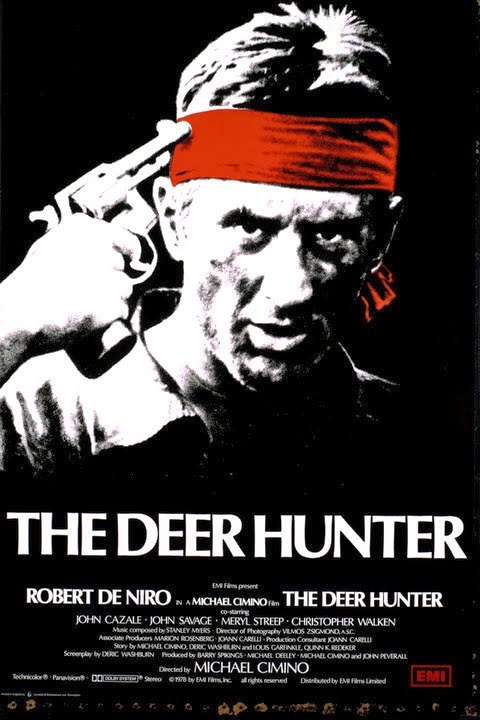

Later in the week, it becomes increasingly apparent that enticing broadband installation companies to the country is more difficult than imagined; impressing upon me the idea that ‘the country’ might well be another country in some people’s eyes. I enter the garage and find myself returning to the box of DVDs, invigorated in the knowledge that my kids found an old Xbox works for watching DVDS. I sort through films we can potentially watch together and The Deer Hunter suddenly stares up at me. I grab it, and in a fit of what Marcel Proust called involuntary memory, recall the time I watched it with my father. Russian Roulette….Christopher Walken…Meryl Streep…De Niro…’nam. So many images burned in my mind….The film that haunted me throughout my youth.

The Deer Hunter appears as if a mysterious force had ushered it into my hand, as if I was rooting through the mélange of objects in the garage unconscious of the fact that I was actually looking for this very film; my mind set on replicating the experience of watching The Deer Hunter as a thirteen year old with my father with my thirteen year old son Anton. Such ‘things’ have a way of acting upon us emotionally; and we end up doing things with our own kids that we did with our deceased parent as a way of safeguarding our memories; as if memory operates via the intermediary of objects. Senses are heightened; breaching the skin we call emotion in the act of repetition.

Anton and I begin watching The Deer Hunter and I find myself announcing aloud that one of the reasons it’s interesting today is it’s set in the working class, ‘white trash’ culture of Pennsylvania, in a community of Russian-American steelworkers. I whisper the words ‘working class’ as if transgressing some unspoken code. And then I hear myself referencing that slogan from Trump’s election campaign, ‘Make America Great Again’ to make sense of the community, or at least the class out of which it came, focused on in this near forty-year-old film. Michael Cimino’s incredible camerawork, the camera moving with such grace from character to character (drawing inspiration from the Italian masters Visconti and Fellini), as they participate in the rituals of the Russian-American steel working community, had retreated from my memory of having watched the film before. The great anthem ‘Design for Life’ by Welsh band The Manic Street Preachers nonetheless begins playing in my head, as we see the workers drink themselves into oblivion, before heading out to the wilderness the next day to hunt the deer from which the film takes its name. Trump’s promise to revive this culture, defined by repetitious labour that at least has a semblance of security, may well be the biggest swindle of all. What’s tragic, however, I hear myself say, is that this class is no longer meant to exist; in many ways it’s the silent majority mobilized and yet at the same time repressed by the election. There is no working class, we’ve been told, or at least the mainstream media seems to think.

I press pause to explain the trump card of the election as the mobilisation of this same class of worker, pointing to the portrayal of melancholic workers destined to be exploited in some way, as evidence of the vast multitudes (suspended between modernist Fordism and its hard repetitive labour and the mobile, rootless capitalism that came after) appealed to by Trump. I think of other examples. Season Two of The Wire also focuses on this lesser seen working class, although in the Baltimore docks when docking has dwindled to a shadow of its former status. It might be, I say aloud, that Trump’s appeal to this culture or class, focused on in the second season of The Wire and The Deer Hunter as dockers and steelworkers respectively (perhaps the human residue of changing economic conditions), propelled his unlikely election win.

The Deer Hunter shifts our attention from the sanguine life of work and play to the sudden insecurity and horror of war. Innocence corrupted one might say; or the face of evil revealed. Mike, Nick and Steve are no sooner in Vietnam then they are taken prisoner by the Viet Cong, and forced to play Russian Roulette against their will. The twenty-minute sequence that follows, which shows how each survives the terror of the game, shapes the characters’ destinies (while anchoring the narrative of the film). It’s a terrifying sequence. It’s not, however, fear I feel in watching for the first time since way back then, but a mix of pleasure and pain adequately defined as sublime. Pleasure comes from admiring the morality of a film dealing with the barbarism of war, recalling the iconic image of Nick, who is played by the angelic Christopher Walken, as he holds the gun to his head so vividly. Pain comes from understanding the trauma represented by returning to play Roulette in the film, as a coda for the more general compulsion to repeat. In the same way Nick is drawn back to the game, obsessed, I feel as if I am drawn to the film itself. But if there’s sadness it comes from the impossibility of returning; knowing the past can only be remembered, not relived.

The injustice of war is undoubtedly the focus of The Deer Hunter, but the act of repeating is the effect of trauma. The film, I would say, concerns the terror of being stuck in the past. Post-traumatic stress disorder is experienced when we are no longer able to focus on the present moment. We keep returning to the trauma, the event itself, in order to realise what it was that affected us so dramatically. The pain that comes from trauma leads to a fixation on things being how they once were; while feeling a sense of disconnection from the present. Hence we repeat, return to the scene, or like Nick in The Deer Hunter, keep playing the fatal game of Russian Roulette.

Nick, Steve and Michael are all, in different ways, victims of trauma. Nick can’t go home, unless he finds who he was before playing Roulette. But to find this person he has to keep reliving the fatal game itself. Steve can’t go home, because he believes he’s not the same person: he’s changed. And Michael, although appearing to be the strong one, the most prepared to ‘pull his socks up’ and readjust to the working life, is stuck too. He tries to return and live normally as before, but he’s haunted by the events in Vietnam. His fixation on reliving the trauma of Nam, although less obvious than with Nick and Steve, materialises in his failing to shoot a deer who appears in his line when hunting, (even though later, in a moment of anger, he subjects Stan to the fate inducing Roulette without consent). This disturbing scene demonstrates, with a degree of subtlety, Mike’s own disturbance: he is unable to shoot the deer unless it has been subjected to the contingent rules, the same odds that ensues from Roulette. That in his head, he’s still fixated on playing Roulette, is proven when he returns to ‘Nam to find Nick and in an attempt to break both their fixation, challenges him to a game.

There is no need to dwell on how The Deer Hunter ends, other than to say that it dramatises the full effect of war in its aftermath; the aftershock which haunts the survivors. Some critics, such as Jonathan Rosenbaum, have found the film polarising, racist and xenophobic, in its exclusive narration of one point of view, but I personally disagree. As opposed to this, I see the film as making victims of all sides, even if the view the narration presents us with is a working class that supposedly doesn’t exist, who appear at the mercy of a power that never reveals itself. The final scene, when the group convenes for drinks after Nick’s funeral, singing ‘God Bless America,’ is poignant. It not only illustrates victimhood as misplaced patriotism, but illustrates an allegiance to nation when least expected. Tragedy lies in the group’s ideological fixation, seeking guidance now from a divine power. It wouldn’t surprise me if the group held up placards, as the credits roll, saying ‘Make America Great Again.’

In the days that follow, the realisation sets in that re-watching The Deer Hunter was not just a bonding exercise with my son Anton but also an attempt to grapple with grief. Maybe The Deer Hunter really wasn’t a random choice, and that – on some level – I was exercising a similar compulsion to repeat to the one addressed in the film. In sitting down to watch a film that I had watched as a thirteen year old with my recently deceased father, I was trying to relive that time again with my son: hold onto to a precious memory that becomes even more sacrosanct when the person we love is gone. Grief, in this sense, is like trauma, a preoccupation with the past, and a remembering that materialises through contact with objects. By travelling to the garage that day I was dipping into my own unconscious. The Deer Hunter is both the activator and the acted upon. In such moments we come to understand memory as not just that which lies within us, which we tap into at will, but that which is incited by objects all around us. Memory is in matter. And to put it another way, memory matters.

Check out Dara Waldron’s previous entries in the Art Encounters Series