Art Encounters | Where Time Becomes a Loop

[arve url=”https://youtu.be/qB_d_OEQrt4" maxwidth=”750"]

“Everything that has been is eternal: the sea will wash it up again.” – Friedrich Nietzsche.

Imagine: you go online to book a trip to Galicia in the North of Spain via Madrid, and you realise it’s too expensive for all of you to get there. You reconsider, and decide to spend a few days in Madrid anyway, before heading south. You have had a few glasses of wine at the time, and you’re cautious not to do anything you wouldn’t normally do. Then the next day you get a text from an old friend to say that on this day twenty years ago you both went to see ‘The Charlatans’ at Exeter University Student’s Union when he was visiting you as a student. You start to think back to 1997, and it then dawns on you that the last time you were in Madrid was 1997. The summer of 1997. In fact, June 1997, the same month that you’re planning to visit Madrid again in 2017. And you haven’t been to Madrid since.

This coincidence has just happened to me. And it’s super weird. X-Files stuff almost. I went on to book the trip to Madrid (or rather my wife did), thought the twenty-year thing bizarre, then realised that everything I was thinking of doing in Madrid when booking the trip I had done before. The fact that it was exactly twenty years ago to the month got me thinking: is this what Nietzsche means by the eternal return? The human condition is one long protracted repetition, defined by the need to repeat over and over (to affirm the life process).

We’ll get back to this. The things I had in mind to do: visit the football stadiums, the Bernabeu and the Vincente Calderon (before it’s knocked down), visit the two major museums — the Reina Sofia and the Prado — and eat nice food. In 1997, I was visiting my sister who was teaching English and living in Madrid, and we did three of these things (the football stuff was with Alberto, her then boyfriend and future husband). We didn’t make it to the Prado, where one of my now favourite paintings, Las Meninas by Diego Velasquez, hangs. But we did see Picasso’s Guernica, which left quite a mark.

I intend bringing the family to see both paintings in Madrid this June, hoping it will visit upon my children the same sort of instruction it had visited upon me. Football and art, one balancing out the other. But I didn’t realise it was exactly twenty years ago, as a twenty-three year old student, that I did these things in Madrid. And of course, the serendipity brought a flush of memories of that other time I’d been in the city. It was at a time in my life when I was single, when I was lonely, and when I had no idea of where my life was going. I loved what I was studying, but deep down I was struggling with the angst that comes from not knowing where I was going in life. I was doing an MA in Criticism and Theory, which is hardly the most market-oriented degree in the world. In some societies, ethnic groups even, rituals help mark the transition from teenager to adult, but in June ’97 I had no idea what I was; a man or a boy. I was twenty-three, but sometimes wished I was thirteen. At other times I wished I was thirty-three, out of the woods of transition. Now, I’m forty-three, and sometimes wish I could go back to my twenty-three year self and tell him everything is OK: the things I yearned for at that time, love and security, would be granted to me. Just tell him to relax.

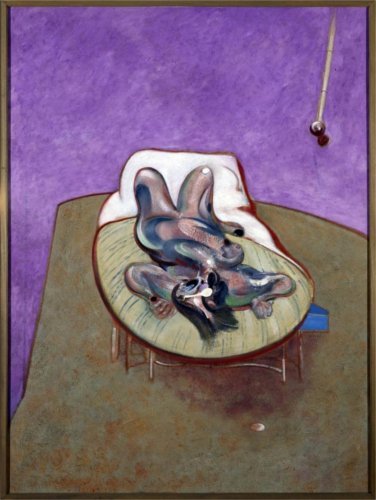

The weird time return stuff got me thinking about my first visit to Madrid, and especially an afternoon spent in the Reina Sofia with my sister Sheila. I remember it was really hot, and we passed all these Spanish sunbathers at an outside pool, before arriving at the museum. We were intent on seeing Picasso’s Guernica most of all, the artist’s vast panacea to the horrors of the Spanish Civil War, but although I was impressed by Picasso’s painting, I remember the visit more for another painting: Lying Figure by Francis Bacon (Bacon titled a whole series of his paintings Lying Figure but the one in the Reina Sofia is known as the 1966 Lying Figure). I remember we were lurching towards the exit when we turned a corner and Lying Figure leant out at us, the explicit use of one particular colour acting as a magnet that drew us in: purple. Lying Figure consists of a single figure lying on a bed against a luminous purple background; the trademark Bacon figure gripped by some passion or fervour.

Just as we were leaving, fatigued from having walked through so many rooms, I was taken aback by such a magnetic use of purple. There was no other painting in the gallery that used purple in this way, and it was magnificent in the subtlety of its rendering. Against a washed-up purple background, that consumes a significant portion of the canvas, is a single lying figure on what appears to be a bed: a body, that although still in the form of a painterly image seems to be twisting and moving. We can’t be sure whether this is two people making love, unifying as one in doing so, or a violent struggle of the self – against its demons – set in the private space of the bedroom. Bacon has this ability to make the still figure appear to be moving, a visual rendering of the process of transitioning from one form to another. And yet, although I remember being struck by the sheer exuberance of the washed purple background, I still can’t recall what it was about the figure that entranced in this painting at that time. I can’t recall what it was then about the body that stopped me in my tracks. All I remember is a sense of awe, and an almost spiritual encounter with the colour purple.

Memory might not serve me correctly but I recall – somehow – that this is the only painting by Bacon in the Reina Sofia, as it was a personal gift to the Spanish government by the artist during Franco’s reign. I knew very little about Bacon back then (the reconstruction of his studio at the Hugh Lane in Dublin was a highlight of the following calendar year: 1998). I knew he was a modern painter with Irish links and that he was gay. I only became aware that he moved in the same mob circles as those portrayed in the Nicolas Roeg and Donald Cammell film Performance (1969) that year, when I was researching Performance (the commercial response to The Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour by Warner Bros.) as part of an essay I was writing. Performance stars Mick Jagger as a reclusive rock star who feeds off the energy and zest of a mobster (James Fox) who takes refuge in his basement. They start to mirror one another over the course of the film, to a point of sameness: at the end they merge together. I intended exploring Bacon’s paintings based on the fact he frequented the murky world portrayed in the film, and because the link between sex, death, violence and human nature, explored by Roeg and Cammell, is a defining feature of his paintings also (paintings that deal with the violence intrinsic to human nature). It is of interest too that Cammell, who co-directed the film and later committed suicide, was a well-known artist and painter, because the film is indebted to the history of painting.

Time-Lapse II

There are those that believe in the circularity of time; that time is comprised of concentric circles leading us back from one point to another, thereby making future, present and past run along a continuous loop. Theories of circular time go back to the Stoic philosophers, through Eastern mysticism and Indian philosophy, to Schopenhauer, and most famously Nietzsche. Nietzsche’s concept of the eternal return is formative here, and is, until now, a concept I struggled to ‘get’. I’ve been frustrated by the concept for decades, failing to align experience with Nietzsche’s idea of return. It was only when I began thinking about this weird serendipity, this twenty year gap that seemed so poignant and meaningful that I came back, looping almost, to Nietzsche. Nietzsche refers to the concept in snippets in books and notes, yet many today regard the ‘eternal return’ as his most important philosophical concept. “Fellow man!” he proclaims in one set of notes, “your whole life, like a sandglass, will always be reversed and will ever run out again — a long minute of time will elapse until all those conditions out of which you were evolved return in the wheel of the cosmic process.”

Because his rendering of the ‘eternal return’ is almost poetic in its reach, it has encouraged scientists, psychologists and philosophers to offer their own interpretation of Nietzsche. That it is affirmative to return, that we repeat the very acts that awaken a cosmic force in us – even if such a force comes from suffering – nonetheless features in all interpretations. Our desire to return, on any level, derives from a life force running through us, an energy we have to cultivate within us. Nietzsche celebrates the return, the repeat act, as an eternal act of affirmation. “If we affirm one moment,” he states in his most famous text The Will to Power, “we thus affirm not only ourselves but all existence. For nothing is self-sufficient, neither in us ourselves nor in things; and if our soul has trembled with happiness and sounded like a harp string just once, all eternity was needed to produce this one event — and in this single moment of affirmation all eternity was called good, redeemed, justified, and affirmed”.

I now sense that such a Nietzschean impulse to return is fueling my desire to ‘affirm one moment’ in Madrid; that time is nudging me in the direction of Bacon’s Lying Figure again, so that that ‘one moment’ in 1997 will be repeated with others who are dear to me in 2017. That the return to Madrid will bring ‘all eternity’ is more difficult to grasp, given that my encounter with Bacon’s Lying Figure in that summer of 1997 seemed so particular to that moment for me alone. But maybe there’s something about the encounter that isn’t unique to ‘me’: that is, testament to an eternal feature of time that until now I have simply been unaware of. And that my decision to go back to Madrid is – on some unconscious level – trying to tell me what this is.

Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award winning novel The Color Purple by Alice Walker, along with the Oscar winning film by Steven Spielberg adapted from the novel, were big cultural events in my youth. It’s possible, given the all-pervasive presence of text and film then that the use of purple as a code for affirmation has stayed with me. Celie, the novel’s heroine, develops a sense for purple as her understanding of what is good in life develops. It is only when she comes to see purple everywhere that the ‘wheels of the cosmic process,’ a mark of the affirmation Nietzsche invests in the eternal return, is grasped: changing ultimately how Celie comes to view the world. It would be nostalgic to think I was in a good place in June 1997 when I first encountered Lying Figure in the Reina Sofia, that I wasn’t grappling – to the point of being unwell – with the same life-adjustments Celie faces in the novel. But it would be churlish also not to think that returning to Madrid in 2017 I am in the midst of a Nietzschean eternal return. I haven’t just booked a holiday to Madrid, but entered a time loop when doing so. And maybe, in this loop, purple won’t just sparkle in a Bacon painting I intend to see again. It’s possible, just possible, that in Madrid the colour purple Celie comes to see everywhere, will appear everywhere for me.

[arv[arve url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HzGrDgu08r8" maxwidth=”750"]