Berlin was Built on Broken Films: Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Herzog, Wenders, Schlöndorff… Fassbinder

Herzog, Wenders, Schlöndorff… Fassbinder

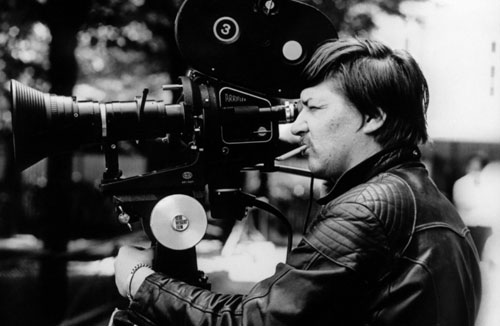

Of the directors active during the period known as the New German Cinema (the 1970s), Rainer Werner Fassbinder was perhaps the most overtly political, and the most personally engaged with his subjects; one of which was the human body, a sensitive topic in the post-war years. In the Anglophone world we still talk about Germany in terms of wars and communism, so it’s easy to overlook the achievements of this younger generation of Germans. It’s easy to forget how liberal and progressive the country has become. Rainer Werner Fassbinder was a part of that. Here’s why.

In 1969, as Fassbinder began his career in film, Germany decriminalised homosexuality. Not one to wait around, in 1975 Fassbinder wrote, directed, and starred in Fox and His Friends. The film opened with two men (one of them Fassbinder himself) kissing each other and continued to show a complex relationship between Fassbinder’s character Franz and his boyfriend Eugen. The interesting thing about the film is that the characters’ homosexuality is not a part of the film’s plot. It simply is, and the plot takes place elsewhere. Fassbinder said of the film:

“It is certainly the first film in which the characters are homosexuals, without homosexuality being made into a problem. In films, plays or novels, if homosexuals appear, the homosexuality was the problem, or it was a comic turn. But here homosexuality is shown as completely normal, and the problem is something quite different, it’s a love story, where one person exploits the love of the other person, and that’s the story I always tell” (Source: Wikipedia)

“It is certainly the first film in which the characters are homosexuals, without homosexuality being made into a problem. In films, plays or novels, if homosexuals appear, the homosexuality was the problem, or it was a comic turn. But here homosexuality is shown as completely normal, and the problem is something quite different, it’s a love story, where one person exploits the love of the other person, and that’s the story I always tell” (Source: Wikipedia)

The film received heavy criticism from the gay community because it drew a rather seedy portrayal of gay people. For example, Deutsche Eiche – the famous Munich gay sauna where Fassbinder himself was a regular – makes an appearance. I think Fassbinder’s refusal to sloganise for homosexuality – which would have certainly helped both the fight for equal rights and Fassbinder’s own life – reflects a deeper mistrust of authorised narratives. For obvious historical reasons, Fassbinder trusts his own visceral and personal experience over prescribed narratives. There’s an almost Aspergic unwillingness to consider the points of view of others that persists throughout his life and work.

In 1978 he made two groundbreaking films. In a Year of Thirteen Moons concerned itself with a trans* character. Fassbinder wrote it as a response to the suicide of his lover Armin Meier (the second suicide in Fassbinder’s romantic life). Although it sounds progressive, watching the film today I can see that it is profoundly offensive. The central character, Elvira, alters her body on a whim and her body is used to analyse her depression. On a biographical note, it looks to be influenced by Armin Meier’s background: he was a Lebensborn child. This was a Nazi experiment to breed Aryan children. That altered bodies were such a visceral reality for young Germans at the time feels almost unimaginable now, and we can see how the New German Cinema felt it necessarry to delve into unsafe territory like this.

His other piece of important 1978 cinema was a segment in the portmanteau film Germany in Autumn. Filmed shortly before Armin Meier took his own life, the film portrays Fassbinder’s relationship with Armin. We see them naked in bed together, we see Fassbinder shouting abuse at Armin, we see them wrestling in the corridors of Fassbinder’s apartment, and then we see a naked Fassbinder masturbating whilst talking on the phone. This was Fassbinder’s perspective on relationships, and it can be seen throughout his work. There are few happy couples in his films. This human complexity that Fassbinder is compelled to portray is remarkably honest, and it refuses to simply suggest that people are good or bad, and refuses to sloganise. When Fassbinder talks about his parents’ generation and their involvement in the Nazi regime, he is really trying to understand them through analysing his own faults as a person. There are no grand narratives for Fassbinder, just damaged people trying to survive.