Growing Up is Murder | Julia Ducournau’s Raw and Dark Coming of Age Films

French writer/director Julia Ducournau’s Raw has won both prestigious critical acclaim and the kind of lurid anecdotal press that old-school schlock horrors wore as a badge of honour – paramedics were reportedly called to a screening during the Toronto film festival after several audience members fainted. Raw is the story of Justine (Garance Marillier), a shy young vegetarian who embarks on her first year of studies at a brutalist veterinary campus. Attending the university is a tradition in her strictly vegetarian family – her parents met there, and her older sister Alexia (Ella Rumpf) is currently enrolled. At first, Justine is the typical protagonist of a coming of age tale – kind and passive, inexperienced and overwhelmed by the anarchic freedoms of rush week. However, after being forced to eat rabbit kidneys as a part of a hazing ritual, she finds herself suddenly prey to a host of intense bodily cravings, the most alarming by far being an appetite for human flesh.

Tonally skewed and wildly unpredictable, Raw is a fresh beast of a film that’s difficult to describe and fully absorb in a single viewing. A horror movie in the looser sense of the horror/art-film hybrid which is thankfully making a big comeback at the moment, it combines youth culture, surreal black comedy and coming of age films to create its own hypnotic and elusive ambience. As original as Raw is, however, it clearly evolves out of a tradition. The rite of passage of the adolescent or young adult into the adult world is a perennial theme in literature and cinema, so much so that the coming of age films often feel generic and predictable. The tone of these movies is usually gentle and conciliatory; our protagonist experiences the pain and uncertainty of their transition to adulthood, but usually find their way in the end, and nobody loses an eye.

Within this tradition, however, there is a smaller sub-genre which you might call the dark coming of age films, where people stand to lose more than an eye. These versions of the rite of passage tale can be divided into films which explore the darker aspects of growing up to a point that borders on psychological horror, and those which utilise the iconography of the horror genre – physical transformations, body horror, vampirism, torrents of blood – to operate as extreme metaphors for the physical and mental upheavals of relinquishing childhood, and discovering the darker currents of sexuality and conflict which characterise the adult world.

Let’s look at some of the non-horror entries first. One of the most brilliant and harrowing dark coming of age movies is all but forgotten about today: Frank Perry’s controversial 1969 feature Last Summer, in which Barbara Hershey made her screen debut. Last Summer focuses on a trio of affluent teenagers (two boys and a girl) who form an extremely close bond while holidaying on Fire Island, New York. The psychological volatility of their hermetically sealed world is gradually unleashed when an outsider – plump, awkward Rhonda (Catherine Burns) – enters their sphere. The cruel dynamics of emerging adult personalities reaches the level of Lord of the Flies in a climatic sequence which is still deeply shocking today. I saw Last Summer once on television many years ago and it seared itself on my brain; it’s a brilliant, albeit extremely unsettling movie which is sadly very difficult to track down at present.

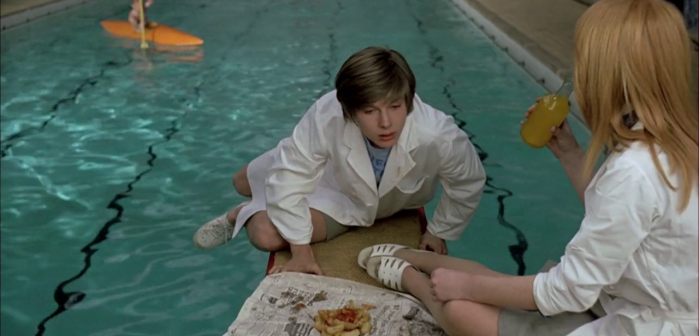

A year later, Polish director Jerzy Skolimowski made one of the greatest of all coming of age flicks in London, the stylish and unique Deep End. Deep End charts the troubled sexual awakening of Mike (John Moulder Brown), a fifteen year old school drop-out who takes a job in a seedy public bath, and quickly becomes infatuated with older co-worker Susan (Jane Asher). Buoyed up by the movie’s absurdist humour and New Wave stylistic energy, initial audiences were shocked by Deep End‘s bleak conclusion; the darker currents of sexual idealisation and obsession, and their capacity to stifle psychological maturity, clearly run throughout the picture, however. Lost for many years, Deep End is now available on blu-ray in a beautiful restoration on BFI’s Flipside imprint. It’s highly recommended; David Lynch once said that Deep End was the only colour film he’d ever “freaked out over.” He may have been exaggerating slightly, but still.

Though more frequently categorised as a neo-noir mystery thriller, Lynch’s 1986 classic Blue Velvet is really the most extreme of all coming of age flicks. Strip away the thriller elements, and the movie basically details the sexual awakening of its protagonist, wholesome college boy Jeffrey (Kyle MacLachlan). The discovery of a severed ear ushers Jeffrey into the dark, dark world of troubled nightclub singer Dorothy (Isabella Rossellini) and screen psychopath to beat them all, Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper). What Jeffrey is really discovering, however, are the repressed undercurrents of his own personality and sexuality. In Jungian terms, Frank is his “shadow aspect”, or the dark side of his personality which he must conquer in order to develop a mature, daylight relationship with Sandy (Laura Dern).

Horror cinema and the adolescent rite of passage are in many respects joined at the hip. Horror often seeks to return us to earlier stages of our psychological development: to our childhood fears of the dark and the unknown, and our sense in adolescence that there might be something sinister or threatening suffusing the everyday world which adults have somehow become inured to – or complicit in. The close conjunction between horror and adolescence wasn’t lost on film producers, who recognised a lucrative market for low-budget shockers in the youth audience. Hence, some horrors dealt explicitly with coming of age (DePalma’s adaptation of Carrie, for example), while others harnessed the hormonal longings and anxieties of young film-goers to create the massively profitable slasher film boom of the early 80s.

The slasher film cycle created an externalisation of youthful anxiety about sexual experience in the form of a knife-wielding maniac who tends to show up whenever young people are freed from parental supervision and likely to have sex. Watching the movies themselves became a kind of dare or rite of passage for adolescents. In many respects, the lurid extremity of the slasher movie captured the hothouse of adolescent emotions regarding sexuality: intense attraction and repulsion, fear of getting caught or perhaps fear of the overwhelming power of sexuality itself, manifested in the looming threat of the maniac. In the slasher universe, losing one’s virginity or being sexually active was often coeval with a visit from the Grim Reaper. This points us to one of the main underlying ideas in dark coming of age stories, going back to Adam and Eve: that with the knowledge of sexuality comes the knowledge of death; or, if not the immediate awareness, then the first movement out of the timelessness of childhood, into the stream of procreation and life that moves inevitably towards death. (One of the horrors of growing up implied in Raw: you become your mother.)

Of course, none of this was really implied in the slasher movies themselves, but it became the explicit theme of David Robert Mitchell’s It Follows (2014), a film which utilised the conventions and latent themes of the slasher genre to create a dreamlike meditation on coming of age. Mitchell evokes the airtight world of adolescence by almost completely removing adults from the film’s mise-en-scene. The movie’s monster, the sexually transmitted It that inexorably follows the protagonists around is in large part mortality itself. Sexuality ushers the characters into adulthood, where an awareness of death inevitably begins to nip at your heels; but sex also works as a temporary weapon against death, through love, solace and the creation of new life. As Mitchell explained in a Guardian interview,

“Jay opens herself up to danger through sex” but “sex is the one way in which she can free herself from that danger. We’re all here for a limited amount of time, and we can’t escape our mortality, but love and sex are two ways in which we can – at least temporarily – push death away. At least, that’s one way of reading it.”

Raw is, of course, different from the films discussed here, but it also carries on many of the traditions of the dark coming of age film. (To keep the length down, I’ve left out George Romero’s Martin (1977), and Tomas Alfredson’s Let the Right One In (2008), both of which explore coming of age through a prism of vampirism.) Like its predecessors, Ducournau’s debut utilises the visual language of horror as an extreme metaphor for the upheaval of sexual awakening; with vivid, visceral imagery, it evokes the seductive and unsettling capacity of the body to be transformed and possessed by the power of its appetites. Only children believe that people actually grow up; maybe that’s why we are always returning to coming of age stories, and why their horrors retain such fascination.

Featured Image Credit