Die Hard With A Vengeance Turns 25 | Does Anyone Care?

It’s hard to see what the cultural impact of the third film in the Die Hard series really is. 25 years later and it’s likely the majority of people think its a perfectly fine action film, many think its reasonable way to pass 2 hours, many think its funny; good set pieces, bombs and guns, good bad guy, he says yippie kai-yay motherfucker. What else do you want?

The truth is, searching for more than that, searching for some sort of resonance, some sort of cultural echo, is fruitless. The impact of Die Hard With A Vengeance as a piece of cinema is not forever seared in the cinefile ether. It’s a run-of-the-mill action movie. In fact the whole Die Hard trilogy (before the 2007 “reboot”) is just a thing, a thing that sits there on digital shelves, being picked up and watched, enjoyed, and left back again, fondly forgotten. If it were not for the seasonal debate as to whether Die Hard is a Christmas film, it’s hard to know if anyone would talk about this film more so than, say Clear and Present Danger or Under Siege.

So, does anyone care that this movie turns 25? Probably not, but this film may be one of the final action movies of its type. The world of action cinema changed in 1995 and by September 2001 the genre as it was known was dead forever.

First, a bit of context. Die Hard With A Vengeance was released in May 1995, five years after Renny Harlin’s lacklustre sequel Die Hard 2, set at Christmas in Dulles Airport. Harlin would go on to make some fine action films, Cliffhanger and The Long Kiss Goodnight being the high points, but the follow up to the 1988 hit was always going to be hard for the filmmaker. He just didn’t share the emotional language to make the characters interesting enough to care for in any meaningful way.

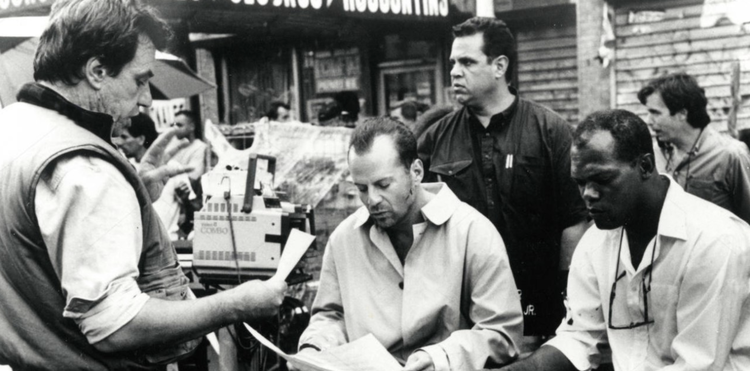

So with that in mind that the original director, John McTiernan was brought back in for John McClane’s third outing. And McTiernan is certainly someone who knows his way around a top class action film that also shows some heart and personal presence. Along with starting the Die Hard franchise he also started the Predator one, and the Jack Ryan series with Hunt for the Red October. He also turned the genre meta with Last Action Hero, a film worth another look. McTiernan would later wiretap a producer on his film Rollerball and end up in federal prison before filing bankruptcy. The ignominious end of his career was 2003’s Basic.

A number of scripts were batted around including one where McClane was fighting terrorists on a cruse liner – that script was rejected due to Under Siege, but the story would eventually find its way to screen in Speed 2: Cruise Control. The script that eventually became Die Hard With A Vengeance came from a story called ‘Simon Says’, by Jonathan Hensleigh, which very nearly became a Lethal Weapon movie. It was then remodelled with McClane as the protagonist.

Bruce Willis returns as hungover and suspended New York cop John McClane who must engage in a battle of wits with a bomb-friendly terrorist as he blows up various parts of Manhattan. He is aided by shop owner Zeus, played by Samuel L. Jackson, as they traverse the city solving riddles and quipping one-liners.

Originally it wasn’t Jackson in the role, but rather Laurence Fishburne. However, he turned it down with hubris, believing he should be taking lead roles only, a decision that must be darkly tinged in regret. It’s set piece after set piece as McClane begins to figure out that the bad guy, played with a cunning glint by Jeremy Irons, is the brother of slain Hans Gruber, the antagonist of the first Die Hard movie. It’s fun. The plot holes gape, the action never ends and sure enough, the bad guy dies with McClane covered in grime and blood.

It’s actually a tidy bookend to a trilogy, both in terms of returning narrative plot lines from the first movie, and the fact that it had atoned for the poorly received second outing. It was a huge box office hit taking in over €350 million worldwide, and this was despite having a climax where a public building containing children was threatened with a massive bomb, considering it was released less than a month after the Oklahoma bombing in which 19 children were amongst the 168 dead.

Willis had said he didn’t want to talk about Oklahoma whilst doing press for this film as he didn’t want to trivialise what had happened there with regards a stupid action movie. But, in America, things began to change after the Oklahoma bombing, culturally, politically and artistically. And over the later part of the 90s, action films began to change. This change was made permanent on September 11, 2001.

The idea of a terrorist bombing in New York could never be the plot of a brainless, blockbuster, run-of-the-mill action movie from that date on and whilst the number of action movies released since then has not ebbed, the content and structure has dramatically changed. Being trivial about something that was now inherently possible and thoroughly frightening meant that action cinema now needed a moralistic angle to approach what was a traditional trope – bad guy attacks America but America fights him off and wins the day. On September 11 America had lost and 3000 people died.

The formulaic plots of Die Hard, Air Force One, The Rock, Speed, Broken Arrow, Executive Decision et al were now redundant as the world was a darker place. From the early 80s these films were blockbuster staples and churned out with relish by the studio systems of Hollywood. They are what they are, and as said before, they don’t exactly rewrite the history of cinema, but they are sheer entertainment, undiluted by fear. These films just didn’t exist after 9/11 and while some action films do address what happened on that date, they did so through the lens of genres, notably science fiction – Spielberg’s War of the Worlds and Matt Reeves’ Cloverfield being the best examples. But the action film had irrevocably changed and was now in need of some point of view, some cynical darkness, something to say that the action we are showing on screen is not just entertainment or escapism, its something that could happen to anyone of us, anytime, any place.

The rise of comic book movies in the mid to late 2000s makes sense. Filmmakers wanted to continue making action movies, but they needed some sort of insulation to pad the reality of this action and violence. Turning the hero from everyday man John McClane to Captain America was important in telling the same stories but also ramming home the fact that the MCU is not the world we live in today and all the scary things that happen could never happen in the “real” world. Nolan’s Batman Trilogy may be the most cynically toned exercise in addressing American fear, hidden behind the cowl of a man in a rubber bat suit.

Action movies are now weighted down by some form of subtext. While the likes of the Mission Impossible and Fast and Furious franchises may be the closest we have to unadulterated entertainment, they are still hindered by the gravity of their own seriousness. Similarly Liam Neeson’s action movie run is similarly devoid of any humour or self reference and the characters of John Wick, Jason Bourne and even James Bond have become hindered by the need to achieve something technically and emotionally taxing.

By the way, these are mostly superb films, both in their story telling and their production but often it’s hard to just switch off and enjoy them. You have to be tuned in and watch every detail, an endeavour sometimes. This is the reason the 4th and 5th Die Hard movies were so boringly average. The viewer had now become accustomed to this new action movie genre and McClane just seemed old and out of touch. Not only had the genre of action movies changed, so too has the viewer.

It seems silly to lament the loss of a genre of movie that was not especially good in terms of the stories it told, the morals it personified or the narrative devices it so often leaned upon. But for a generation of filmgoers, the late 80s and 90s were the golden age of escapism with bone fide action stars from the likes of Van Damme and Seagal to Schwarzenegger, Willis and Stallone.

It’s 25 years since Die Hard With A Vengeance came out and upon rewatching, it was supremely refreshing to just sit back and enjoy the show. No concern about how the plot works, or where it fits in the cinematic universe. No concern about understanding the subtleties of the subtext or the thematic beats. No worries about the technical accomplishments of each action sequence or how the protagonist is shoving American foreign policy down your throat. For a film full of riddles and tests, there are none here for the viewer. Who cares how they get the 4 gallons into the 5 gallon jug. It doesn’t matter to you unless you want it to matter. If you want it to matter, you’re missing the point. The riddles are for McClane – sit back and enjoy it.