Subtext | La Vague Moderne: Three Recent French Films

French cinema has always had a reputation for artistic flair. The very word for a great director who brings his vision to the screen, auteur, comes from the French word for author. In France cinema is idiomatically known as le septième art – the seventh art, combining architecture, sculpture, painting, music, poetry, and dance. This is hardly surprising – thanks to the efforts of the Lumiere brothers, France is sometimes considered to be the birthplace of cinema. Although movies coming out of France no longer dominate internationally the way they did during the “New Wave” of the 60s, it still has a thriving film industry that is well worth the time of any cinephile. This time we’ll look at three recent movies, the first of which applies a typically French lens to the modern trend for superhero movies.

How I Became A Super Hero (2020)

How I Became A Super Hero is based on a novel by Gérald Bronner, who is better known as one of France’s leading social scientists specialising in cults and the science of belief systems. This is a film that is as interested in showing the impact of superpowers on society as it is in showing off superpowered antics. (Being a French film, it’s also got a lot more focus on interpersonal relationships and the mundanities of life than the average Hollywood movie.) After a short scene, the film proper opens with our protagonist Moreau (played by Pio Marmaï) getting ready for work. He is a police officer investigating superpowered crimes, in a world where superheroes are an accepted part of life. (A commercial with a superhero shilling macrobiotic diets drives home this point.) In a classic setup he’s been assigned a new partner Schaltzmann (played by Vimala Pons. While the two initially don’t get on, the movie doesn’t let this linger and believably navigates their route to friendship. Together they’ve got to investigate a crime spree tied to something new and sinister: drugs that appear to give non-powered people temporary superpowers.

I like this movie. It reminded me of the best of the superhero movies of the 2000s (like Push) before the MCU juggernaut loomed quite so large in popular culture. The actors are charismatic (veteran Belgian actor Benoît Poelvoorde steals the show as elderly ex-hero Monte Carlo) and the story moves at a good pace, giving its villain a believable motivation and not falling into the trap of feeling a need to make the stakes too great. The world is sketched in at the edges but in a believable way. One classic comic book series it reminded me of was Powers, by Brian Michael Bendis, and I was delighted to see his name pop in the “Thanks” section of the credits (alongside Alan Moore, Bruce Timm, and several other comics legends). How I Became A Super Hero is unashamedly for fans of the genre, but those viewers will find it a rewarding and fun watch.

Oxygen (2021)

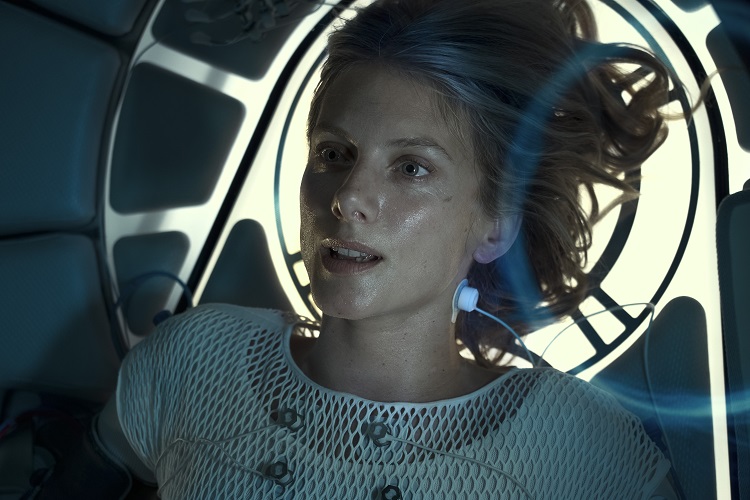

A less fun watch if you’re claustrophobic, but still compelling, is Oxygen. The plot is almost painfully simple. A woman wakes up inside a high-tech coffin, which turns out to be a cryogenic pod. She has no memory, nobody is coming when she calls for help, and her oxygen is running out. That’s the setup and the entire setting for this movie, which manages to take some twists and turns despite its apparently simple premise. Outside of flashbacks, the only actor we see onscreen is the woman herself, played by Mélanie Laurent. She’s most recognisable to the English-speaking audience for her performance as Shosanna Dreyfus, the Jewish cinema operator in Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds, though she’s starred in dozens of hit films and won numerous awards. She’s also an accomplished director, having co-directed the award-winning crowdfunded documentary Tomorrow. The director of Oxygen is Alexandre Aja, a French director who is famous for directing Hollywood horror movies (such as Horns and the 2006 remake of The Hills Have Eyes). The only other character we see on screen is Malik Zidi, who would be a very familiar face to French movie and TV viewers but less so to English-speaking audiences.

Oxygen is the first script written by Christie LeBlanc, who was previously best known for writing the TV series How To Make A Reality Star. She sold the script for Oxygen back in 2017, and originally Anne Hathaway was going to play the lead role. That fell through, and by February 2020 Noomi Rapace was cast in the lead with Franck Khalfoun directing and Aja producing. (The two had worked together in those roles before in 2012 on a film Aja wrote called Maniac.) Within a few months Laurent replaced Rapace and Aja moved to directing, with Grégory Levasseur (a long-time Aja collaborator) taking on some of the production work. Fortunately all of this chopping and changing took place before filming began, and the resulting film did not suffer. Oxygen is a highly polished masterclass in acting, pacing, and tension. Despite the confined setting the story moves extremely quickly, and the scope of the film is a lot wider than you might think. Fans of science fiction and of tense thrillers will find plenty to enjoy in this one.

The Most Assassinated Woman in the World (2018)

The last film we’re looking at is one that plays directly into my interests – a period piece diving into a strange corner of historical lore. In this case it’s the Grand Guignol Theatre in Paris, which opened its doors in 1897. “Guignol” is a puppet character from the French equivalent of Punch & Judy, but the name now is more associated with the gory horror shows that the theatre became famous for hosting. Founded by Oscar Méténier in a building that was once a church, the original mission of the theatre was to show life as it truly was. Max Maurey took over the theatre the following year and shifted the focus to horror, helping to define the genre long before Hollywood. His chief playwright was André de Lorde, who was by day a librarian and by night a writer of horror. (He was also the heir to an aristocratic title, comte de Lorde, though he inherited no fortune alongside it.) De Lorde’s most famous collaborator was the psychologist Alfred Binet, who helped him write realistic plays about madness and about the horrors of mental asylums. (Binet is notable for being an early pioneer of psychometric testing, to help identify children with developmental disabilities.)

The most famous actress of the Grand Guignol Theatre was Paula Maxa (born Marie-Thérèse Beau), and she’s the main character of The Most Assassinated Woman in the World. After a short cold open establishing that there’s a serial killer on the loose in Paris, we get a monologue from Paula herself (played by Anna Mouglalis) as she describes all the various ways she has been killed. “And yet, I am still here.” Paula says that she has died over 10,000 times on stage (which is actually on the low end of official estimates), and we watch along with the audience as she dies once more. The film takes you through the experience of being a customer at the theatre before it dives into its plot (which involves a serial killer, Paula’s own mysterious past, and a journalist named Jean played by Niels Schneider trying to piece it all together). We see the passion that people have for the shows, and the protesters convinced that all kinds of depravity are going on. As opposed to the mild amount of depravity actually taking place, of course. (Oh, and I should give you a content warning for not just gore, obviously, but also sexual violence that forms a major part of the plot.) This is not a film that goes for easy answers. Paula is empowered by her acting, but it also allows her to avoid confronting her trauma. We naturally feel that the protesters are in the wrong, but the theatre is connected to the murders. On the other hand, the protestors seem a little too into the act of protesting. A general sense of amoral ambiguity permeates the proceedings.

The film is anachronistic in several respects. It takes place in the 1930s (in the shadow of the war), though it features a cameo from Alfred Binet who died in 1911. It shows the final days of the Grand Guignol theatre, though the theatre actually stayed open until the 1960s. Most notably (and where it slyly acknowledges these issues) is that it shows Paula contemplating leaving the stage for a career in film. In reality she was in several films in the 1910s, appearing alongside Irma Vep in the Les vampires series. She says in her memoirs that she decided she preferred live performances, and she’d go on to work on the stage for more than a decade after that. The film tips its hat to this contradiction by having Jean and Paula go to the cinema together, where they watch the real Paula Maxa be murdered on the big screen.

Anachronisms aside, this is a film that has a lot of affection for its subject while also not shying away from its issues. The protesters are portrayed as kooks, but are then shown to be right – there really is a killer being inspired by the shows. The nature of the shows are contrasted with a reality where Jean bears the wounds of a very real pistol duel. Director Franck Ribiere has primarily worked in documentary films, and that’s the lens he brings to this production, mixed with a level of hallucinatory horror that leaves you questioning reality. This is far from a perfect film but one that in itself seems to embody the spirit of the Grand Guignol. It may be wrong in details, but it feels very true to the spirit of the theatre of blood.