Film Review | The Girl on the Train runs out of steam

I came late to the phenomenon of The Girl on the Train, and when I eventually read Paula Hawkins’ bestseller, couldn’t help but wonder what all the fuss was about. Would the film adaptation add anything to the experience?

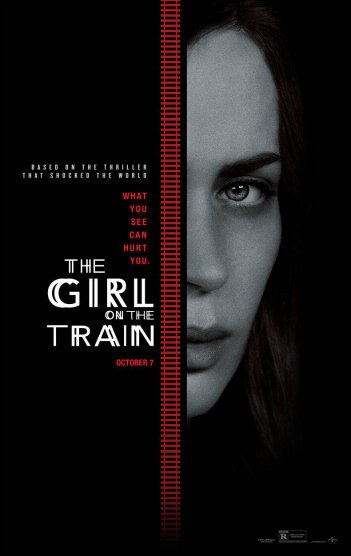

The Girl on the Train

The Girl on the Train is the story of three women – Rachel (Emily Blunt) an alcoholic divorcee who travels into the city each day watching the world from the window of the train. She is especially curious about Megan – a young woman (Haley Bennett) whose home she passes and who seems to have everything Rachel does not – expensive real estate and a loving husband, Scott (Luke Evans).

The Girl on the Train is the story of three women – Rachel (Emily Blunt) an alcoholic divorcee who travels into the city each day watching the world from the window of the train. She is especially curious about Megan – a young woman (Haley Bennett) whose home she passes and who seems to have everything Rachel does not – expensive real estate and a loving husband, Scott (Luke Evans).

To add salt to Rachel’s wounds, Megan lives down the street from Rachel’s ex-husband Tom (Justin Theroux), his new wife, Anna (Rebecca Ferguson) and their baby, now living in her former home.

One day, from the train, Rachel sees Megan with a man who is not her husband and is furious to discover she is a cheater, like her ex. Rachel gets spectacularly drunk, climbs off the train near Megan’s house and staggers into the night. She wakes the following morning with no memory, a head-wound and later discovers Megan is missing.

Uncertain of her own drink-fueled actions on the night in question, Rachel can’t resist probing further and becomes involved with Scott, Megan’s bewildered and angry husband. When Megan turns up dead, the layers of these women’s lives and relationships peel back in a series of flashbacks – uncovering the lies and deception brewing beneath seemingly perfect facades.

Unreliable Narrator

A black-out drunk, with no memory of her actions when drinking, is a promising set-up for the story’s narrator. Unfortunately, some mystery is lost in the transformation to screen. We see from the off that Rachel is drunk, for example, and the series of black-out episodes that added credibility to her alcoholism on the page become truncated and less convincing on film.

Comparisons with Gone Girl and Amy Elliott Dunne – the ultimate unreliable narrator and mind-fuck – are perhaps inevitable. David Fincher spent two and half years bringing Gillian Flynn‘s story to life, where The Girl on the Train was fast-tracked to take advantage of the book’s phenomenon. It’s a polished production, borrowing more than a little from Fincher’s signature dark visual tone but has neither his sureness of touch nor the deftly woven, anxiety-inducing soundtrack.

A hideous transformation?

Emily Blunt doesn’t entirely convince as a bottomed-out alcoholic, though she has her moments. In press interviews, she talked of her ‘hideous transformation’ to play a woman in the depths of the spiral of addiction. Unfortunately, Blunt ‘hideously transformed’ looks like the rest of us on a good day so it’s hard to empathise.

However, Blunt does capture the character’s acute vulnerability in scenes that are often movie cliches – the AA meeting, the therapist’s office – and the bathroom scene where Rachel descends into a drunken rage at the feckless cheating Megan, is genuinely shocking. I can’t help but wish there had been more of this duality. A more abrasive, less likeable Rachel would have upped the dramatic stakes considerably.

Bennett is precocious as Megan, Ferguson luminous as Anna, Evans and Theroux are able but have little to do. Edgar Ramirez and Allison Janney, always worth watching, add ballast as Megan’s therapist and investigating officer, respectively.

The change of location from London to New York tells us nothing more than Hollywood producers / US audiences don’t much care about what happens to people on trains in England.

There are a few unintentionally funny moments. Ferguson‘s yummy-mummy Anna explains how going to the farmer’s market and selecting the best organic product to puree for baby is work, which is why she needs a nanny to take up the slack. Rachel, spying Megan from the train – preening on the balcony of her house in her undies like a Victoria’s Secret model – solemnly pronounces she must be ‘an artist or something creative’, suggests Rachel is not only drunk but high.

From Book to Film

The problem with the book, and consequently the film, is that it isn’t much of a thriller – a narrow cast of characters means you don’t have to look too hard for a culprit. The plot executes a few corkscrew turns to keep things chugging along but ultimately doesn’t surprise.

It’s heartening to see a studio film with females in the spotlight, but it niggles that each of these women is essentially the same. They don’t have jobs or money troubles – even Rachel, whose alimony payments conveniently make all this drunken train travel possible. They live in the suburbs – lovely houses and hot sex with ripped men/husbands appear to be the summit of their ambition – even Rachel, who already knows the perfect house/marriage/husband is a lie.

The Girl on the Train is not so much a crime thriller as the edgy grown-up daughter of the Aga Saga, where a dead body on the doorstep is less a human tragedy than a potential blip in house prices. It goes a long way to explaining the book’s popularity.

Author, Paula Hawkins was apparently won over to a film adaptation by the promise of a ‘dark, sexy thriller’. This isn’t it. If you haven’t already read the book, it might punch your ticket but, for me, The Girl in the Train never really leaves the station.

The Girl on the Train is on general release from from Oct 7.

Featured Image: Universal Pictures