The Exorcist – 20 Years After Its Irish Re-Release

It’s strange to write about the 20th anniversary of a film that is actually 45 years old. Released in cinemas in America on St. Stephen’s Day 1973 and around the world in early 1974, The Exorcist is celebrating an anniversary this year in Ireland as, until 1998, it was effectively banned. In the early 1980’s, with the coming of VCR, The Exorcist was granted a certificate for video release in Ireland and the UK, but crucially not a licence for broadcast on television. The certificate for video release was later revoked by the British Board of Film Classification toward the end of the 1980’s thus meaning The Exorcist was unavailable for home viewing in both Ireland and Britain (though to be totally honest, the film never made it to the “banned list”, it was not a video nasty, it just was not allowed a video release). This pseudo ban was lifted just in time for Halloween, 1998 a full 25 years after the film was first released.

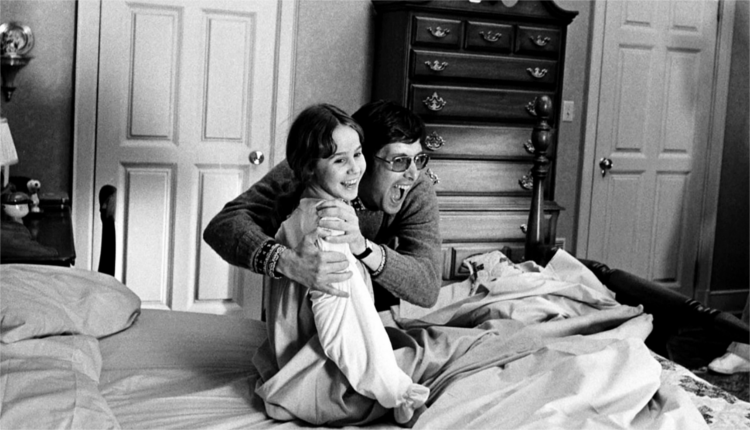

The gap of a quarter of a century and the myth that invariably built up to fill that void worked both for and against The Exorcist. The 25-year embargo created a mystique that, as the years crept by began to grow toxic as opposed to therapeutic. On re-release in 1998 it was a smash, staying in some theatres right up until Christmas, yet while the demand was phenomenal the reception among the first-time viewing public was not necessarily so. What audiences expected, what had been built up in their minds was not the terror-fest that they had been hoping for, but a slow burning atmospheric chiller. For a generation brought up on gore-filled slasher films and cut-rate torture porn, a film depicting a virtually bloodless struggle between two priests and a demon for the soul of a 12-year-old girl fell a little flat and audiences seeing it for the first time thought, “that’s it? That’s what all the fuss was about?”

Younger audiences laughed at the 360-degree head spin or at the spider walk (which was re-introduced in the director’s cut that followed soon after) – on my first viewing of The Exorcist I couldn’t understand what the bulk of my friends I saw the film with were laughing at. I was petrified, and it only struck me later that while we were watching the same movie, we were coming at it from two different viewpoints. It wasn’t the effects that scared me, but the story. The power of the Catholic Church in the late 1990’s was nowhere near as strong as it was in the mid 1970’s. People were no longer put off watching The Exorcist for fear of what their mother, father or priest would think of them for doing so. Instead of being afraid, people now laughed at The Exorcist.

That was my first abiding memory of The Exorcist. Then I thought, but now I am certain (the benefit of 20 years and countless shoddy imitations), that The Exorcist is far too important a film to be laughed at. No matter your level of faith, The Exorcist at its very core details a battle between good and evil (be that morally good and morally evil or physically good and physically evil), the corruption of innocence and how people selflessly consider the ultimate sacrifice to save the good in the world.

Remove the concept of religion and any references towards the Devil and God from this film and you have a story that is fundamentally concerned about a group of people who are willing to surrender their own lives to save the life of a little girl, someone who is a stranger to them. This, essentially, makes The Exorcist a morality tale; that is what makes it powerful, not make up effects, the self-mutilation with a crucifix or practical effects.

One of the most striking features of The Exorcist is Fr. Karras and the journey he goes on, not just Regan. Fr. Karras is having a crisis of faith and he does not, at first, believe that she is possessed, saying to her mother, “Look, your daughter doesn’t say she’s a demon. She says she’s the devil himself. And if you’ve seen as many psychotics as I have, you’d know it’s like saying you’re Napoleon Bonaparte.” It is this scepticism that draws the viewer in. While she may be the focus of the film, it is not solely her story being told. This is evidenced early in the possession portion of the film, when Regan has practically been consumed by Pazuza, the demon tormenting her. As Fr. Karras and the demon speak, bearing in mind that at this point Fr. Karras does not fully believe Regan is possessed, they say:

Demon – What an excellent day for an exorcism.

Fr. Karras – You would like that?

Demon – Intensely.

Fr Karras – But wouldn’t that drive you out of Regan?

Demon – It would bring us together.

Fr. Karras – You and Regan?

Demon – You and us.

This little passage delicately foreshadows the horrendous odyssey that Fr. Karras undertakes, fighting his own demons as well as those possessing Regan, demons designed to test his faith. At the start of this film Fr. Karras is a broken man, a broken priest to be more precise. He is questioning his faith and his place in the Church. By the end he has sacrificed his own life, maybe even his own soul, to save the life and soul of Regan. He has laid himself bare to the demon but also to his own God and by witnessing true evil, in being blinded by darkness he eventually finds the sanctuary of the light.

That might sound like an attempt a poetry or some wishy washy meaningful passage on the power of religion but it shouldn’t take from the fact that Fr. Karras finds his faith when he needs it and maybe his suicide (a most abominable thing in the eyes of the Catholic Church) to rid a child of a demon tormentor can be seen as some kind of atonement for his lack of faith. As Fr. Karras himself says to his superior early in the film, “I need re-assignment, Tom. I want out of this job. It’s wrong. It’s no good…I can’t cut it anymore. I need out. I’m unfit. I think I’ve lost my faith, Tom.” Mirror that with the Fr. Karras at the very end as he recognises the true power of the demon, who sits smirking at the corpse of Fr. Merrin. Fr. Karras rages and commands the demon to, “Take me! Come into me. God damn you! Take me! Take me!” That sacrifice is what makes The Exorcist truly special, not the make up or the now infamous, shocking sequence with the crucifix. It is the human, not the demon, that lingers with me when watching The Exorcist.

Horror films were forbidden in my family home when I was a kid and even mention of The Exorcist was enough to illicit a scornful look from my father, as if those two words were an invitation for all manner of evil things to befall the house and those in it. I’m not sure if this is just an Irish thing, or a Catholic thing or both but any discussion about the Devil through popular culture was frowned upon. Deeply entrenched in not only Catholics but all religions is an anxiety of evil. And how do we combat it? We don’t talk about it. But, as Jeffrey Burton Russell, author of The Prince of Darkness: Radical Evil and the Power of Good in History, says “Evil exists, but it exists as a lack of good, just as holes in a Swiss cheese exist only as lack of cheese.”

So, if we are not demonstrably pure, does that mean we are markedly evil? Is that why we are, dare I say, afraid of evil and its very mention? Does evil only exist if we are not undertaking good deeds? Because evil is everywhere, its discussion populates every Gospel in the Bible. It is not that the religious people are ignorant to evil, quite the opposite in fact, but we have been programmed to equate anything enemy with everything evil.

Don’t masturbate, it’s evil. Don’t use bad language, it’s evil. Don’t think impure thoughts, it’s evil. These things, as common as crossing the street have been ingrained in us as evil. We therefore, as human beings are ripe for the tempting. According to the Jewish Apocalyptic book of Jubilees, it “insists that every creature, whether angel or human, Israelite or Gentile, shall be judged according to deeds, that is, ethically.” If we act in an evil way or think in an evil way, then we shall be judged, but shall we be judged as evil? It is hard to wash away that type of fear.

Is this why The Exorcist was so tantalising and polarising a prospect for the cinema going public in the 1970’s? Evil, which had been preached about in church was now coming to your cinema screens. How could people not show an interest? Elaine Pagels in her book Origins of Satan states, “what fascinates us about Satan is the way he expresses qualities that go beyond what we ordinarily recognize as human. Satan evokes…the greed, envy, lust, and anger we identify with our own worst impulses.” This is in fact corroborated by Fr. Merrin during a break from the exorcism. Fr Karras asks, “Why her? Why this girl?” To which Fr. Merrin replies, “I think the point is to make us despair. To see ourselves as… animal and ugly. To make us reject the possibility that God could love us.”

By starting a lecture in the above paragraph about God and religion I feel I am doing a disservice to the craft and skill of the filmmakers. When it came to unnerving his audience, William Friedkin, the Oscar winning wunderkind of early 1970’s American cinema tried as many things as he could to create both a sense of unease in the viewer but to also add as much grounded realism as he could. The subliminal messages in the film are evidence of the attempts to disquiet the audience. The momentary flash of the demon Pazuzu’s face as seen in the hood of the cooker early in the film or early in the possession sequence jolt the audience, but you are not entirely sure why (an effect expertly riffed upon in Fight Club).

In the roles of two of the supporting priests, Fr. Dyer and Fr. Bermingham, Friedkin cast two actual priests, Reverend William O’Malley played Fr. Dyer and Reverend Thomas Bermingham played himself, Fr. Tom the President of the University. Fr. Dyer, the piano playing cleric in the party scene early in the film, administers the last rites to Fr. Karras as he lies dying on M Street, a scene played with such intensity you would be hard pressed to think that O’Malley wasn’t an actor. Yet the emotion in O’Malley’s voice, face and body movements is the stuff of legend. Apparently after countless unusable takes, Friedkin offered the priest some advice on how to play the scene and then, just as the camera was about to roll punched O’Malley hard across the jaw. The shake in his hands, the shock and upset in his expression is genuine, all from Friedkin’s right hook.

And speaking of the ending, what a way to close out a film concerned with demonic possession. There is hope in the ending, depending on which version you watch. In the original, Chris MacNeill gives Fr. Karras’s medal to Fr. Dyer and drives off, leaving the emotionally shattered priest holding the last relic of his dead friend before cutting to black. In the Directors Cut, Fr. Dyer returns the medal to Chris MacNeill and then meets Lt. Kinderman and they walk away into the distance talking amiably between themselves about what’s playing in the local theatre. While it might not be much, it certainly changes the tone of the ending from one of pessimism to optimism, to hope for the future as opposed to contemplation of the past.

There is so much in The Exorcist to love and to fear, so much cinematic magic that still stands the test of time. The Exorcist is the yardstick that all possession films are measured against, and for good reason. It has heart and soul and it asks questions without getting or giving all the answers. You must work at this film to find the meaning in it and even then, your meaning might not be mine.

As stated earlier, The Exorcist at its core is a morality film and what greater victory for the immoral is there than the corruption of innocence. This is the power that The Exorcist wields against the audience – the demon attacks a child, the very personification of goodness. By the late 20th Century, society had moved away from the idea that church and state govern our lives and our ethics to living autonomously, responsible for our own actions. This is where The Exorcist, as released in Ireland in the late 1990’s, may have failed. We were no longer afraid of the church, we were in fact openly dismissive of it, an echo of rumblings of discontent among the lay and faithful about scandals and cover ups of abuse and indecency. Be that as it may, The Exorcist is still a powerful film, one that will linger in the memory long after it has ended and a film that should never be forgotten or dismissed.