My Problem With Death

Death is the dirigible in the bathtub.

I can’t help but notice that whenever anyone falls off the twig, no matter how esteemed or beloved, pretty much everyone else just keeps on going, even those who shared the demised’s bathroom. Somehow going on seems tasteless. But the evidence suggests that almost everybody does go on, and usually without the kind of sustained fanfare it would be reasonable to expect. Take a bathroom partner’s calm reorganization of dental care components. It’s as if the goer-on knew all along what was coming.

It’s not that I don’t want life to return to some facsimile of normal after I bite the dust. But it should be really hard. My friends and acquaintances will need professional help to get through it (some will end up in detox) and all the color will drain out of existence.

I really try to imagine death, or rather I try to imagine being dead. When I attempt to imagine the process, or act, of dying itself, it feels pointless and embarrassing. But imagining being post-live is beyond me; I can’t do it. No matter how empty my bladder is and how inert I make myself, a tiny spark of hope flits in and out of my brain that somebody at a higher pay grade will witness my attempt to get control, take pity, and grant me an exception.

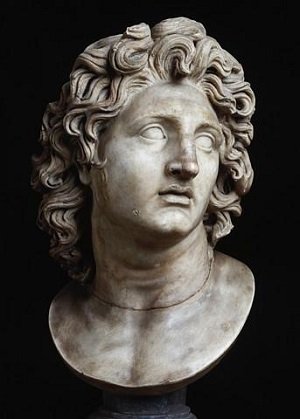

Also, I could maybe, just maybe, someday get over the utter impossibility of not being around to find out what happens except for the fact that EVERYONE is forgotten, eventually and without exception. True, we remember Alexander the Great. We even have his airbrushed likeness on some coins. But nobody alive knows what he was like in the morning or whether he married somebody just like his mother. He began every day with a bath and ceremonial sacrifices, and was 22 and a brilliant general when he conquered the Persians, but we don’t know if he had any Persian friends or liked the way they danced, or could do hysterical impressions of Thracians or Illyrians.

But EVERYONE being forgotten brings me back to the fact that I will be forgotten, too, and this fills my thoracic cavity with molten dread, making me want to shoot up my TV set in order to impress Debra Winger.

Think about it. Nothing gets carried forward. Forget my puny concerns, nothing made or thought or cherished by people, no matter how profound, survives. I guess what does survive is DNA, cold comfort for sure. The story DNA tells, however epic in its sweep, is a little dry.

It feels laughably impossible to leave the building without knowing what ended up happening in ongoing, critical arenas of action. What will end up happening to the Falklands, or Renée Zellweger? Will she get back in the game and live up to her amazing potential? And yes, that means that in my head I believe that there is such a thing as “ended up happening”, as if time stops or a thing gets to a point that represents the end of its development and it goes on being perfectly able and content to remain the same. Yes, yes, I understand the buffoonish absurdity, but this notion asserts itself without a shred of permission from me. When I patiently propose to myself that the state of the material world will drop off my radar when my time is up, I’m tilted into an odd anxiety. Somebody in there really has got to have things stay as they are.

I’m inspired by Robert Duvall’s character’s example in the movie Get Low, when he gave himself a funeral before he died. He needed to confess a bad thing he did as a young man to all the people he knew and didn’t care about. But, I want to hear what people are going to say about me. Folks are inspired to dig deep at a funeral – no, digging is not even necessary because when a chasm opens up in your life and upends the landscape, for a while all you have is deep. I’m sure it would be nice to hear generous assessments. But I really would be in it for the shock of picturing my life lived in the light of the testimonials, instead of from the tired perspective that lives in my head and works too hard.

So I’m not worried that my friends are going to be feeling blasé under a mask of grief. I’m worried that, after the funeral, they are going to stop at the lav on the way to the church basement, dine on non-GMO free-range barbecued chicken followed with a slab of either banana cream or peach pie, and then drive back home, where things are comforting and familiar.

All this talk about the End makes me realize that I might check out without people knowing certain things about me that, frankly, have gone underappreciated. For instance, very few people know firsthand about my remarkable memory for telephone numbers. I can dial (people are still going to be saying “dial” in 6000 years) a number 2 or 3 times, while paying attention, and it’s embedded in my brain. I still remember Richard Flohr’s number from 7th grade: 883-3731. My wife (who I will refer to as Maureen) has learned that I am a reliable source of phone numbers, kind of like when a squirrel figures out there are always sunflower seeds under the bird feeder. But she never stops and says, “Wow, it’s so amazing you can remember telephone numbers like that.” It’s the kind of thing you marvel at after someone is gone.

via aaroncheak.com

Further, it is distressing to think that when I go some very essential things are going to vanish as if they never meant anything. My massive, lavishly illustrated volumes of The Temple of Man, by R. A. Schwaller de Lubicz, for example. S de L was a French student of alchemy who camped out for 12 years at the Temple of Luxor in order to plumb its mysteries. He perceived that the design of the Temple reflects shockingly sophisticated astronomical knowledge, and exactly mirrors the subtle and physical structure of the human body. I once tried to penetrate these gigantic tomes, not quite making it a quarter of the way through volume #1. They nevertheless now occupy a position of honor on my office bookshelf, just one small example of hundreds of things whose meaning is etched in my soul. After I go they become objects suddenly devoid of significance until another sentient being casts an eye upon them and invests them with a completely different and very possibly inferior meaning. My meaning is gone, period. Talk about death, boy, that’s it.

Meanwhile, people keep dropping like flies. Somebody every day I either knew, or wish I knew. Sometimes I’m reminded of folks I haven’t thought of in a very long time, so long that they could well be deceased without me knowing. Like Art Carney, one of my all-time favorite people. Did you see him with Lily Tomlin in “The Late Show”? He plays a hard-of-hearing, aging detective and my favorite scene is when several gunshots crash through the windows of the vestibule of his rooming house where he is chatting with his landlady. It’s after dark and he hauls out a rather large handgun and limps bowlegged down the front steps while the shooter is jumping into his car and speeding away. Carney stops, and unhurriedly extracts his hearing aid from his ear, letting it dangle on a cord (the coolest moment in the movie because his chance to get the bad guy is shrinking with every second and yet he knows he can spare a moment to get a little more comfortable). He’s still wearing his hat as he raises the pistol and squints down the barrel through his Coke-bottle lens glasses as the crime car careens on its final turn out of sight. Carney fires the gun once and blows out a rear tire, crashing the car and forcing the nattily dressed hood to flee on foot. Too tired and slow to give chase, Carney turns around and goes to bed.