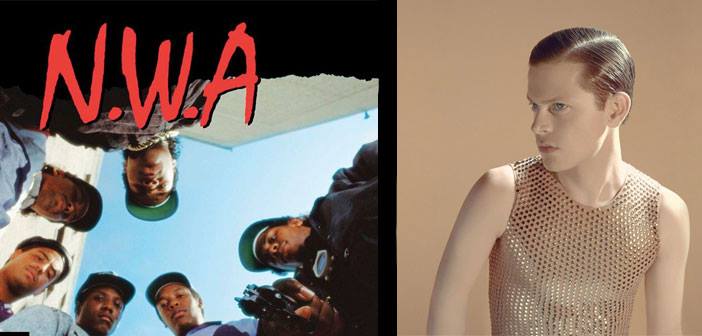

Parallel Pride: The Surprising Link Between N.W.A and Perfume Genius

You would be hard pressed to find two acts that exist on the opposite ends of the musical spectrum to the degree that Perfume Genius and N.W.A do. The former is a soulful singer/songwriter known for writing intimate, sparse songs about his relationships with men and the casual homophobia that surrounds him while the latter is the ground-breaking gangsta rap troop of the late 80s that struck a powerful chord with the disenfranchised black youth of America and elsewhere.

The contrasts go beyond just the music. N.W.A’s beginning was an urban communal experience – a group of friends, all from low income families, got their start by rapping on the street corners of Compton -while Perfume Genius’, who would write his tender piano-based songs in his bedroom and upload them to MySpace, was one marked by isolation. The bravado of the five-man, testosterone-fueled hip-hop group made them the embodiment of machismo but Perfume Genius – with his flamboyant stage persona – is very much an artist who likes to challenge traditional notions of masculinity.

To say these are acts with some stark differences would indeed be a gross understatement but there is certain kinship that someone like Perfume Genius shares with a group like N.W.A. With both their music and image they rally against a misinformed identity – whether it be based on their race or sexual orientation – that the media and/or society has placed upon them. The two represent the fiery reaction of a consistently marginalised and oppressed group that is determined to get the ‘powers that be’ to acknowledge their grievances. More than just that, they share a pride in what it is that makes them ostracised and a willingness to be accepted for what they are. To put it bluntly, If N.W.A were unapologetically black, then Perfume Genius is unapologetically gay.

[iframe id=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/Z7OSSUwPVM4"]

Mike Hadreas – the man behind the Perfume Genius moniker – would probably not be too appreciative of being compared to musicians that come from a genre which has a well-documented culture of homophobia. To quote one uneasy instance from N.W.A’s own catalogue, Ice Cube spits with gusto on ‘Fuck Tha Police‘ that L.A. Cops must be “fags” because of their unwarranted crotch-grabbing during searches. Just last year, Hadreas hit out at Eminem for some particularly grotesque lyrics (those Lana Del Rey punching ones) by selling T-shirts at his gigs with the visage of the Detroit man, emasculated in full drag, plastered on in almost iconoclastic fashion.

It’s clearly not a world that someone like Hadreas would identify with. Nonetheless, the two occupy a similar space. What the emergence of a group like N.W.A says about the mindset of a disaffected and underprivileged black population of the late 80s is arguably similar to what Perfume Genius’ emergence says about certain aspects of the LGBT population’s mindset today. They are both groups that had finally been enjoying some representation – the music industry being no exception – after spending years on the sidelines. After reaching the platform, however, they were left to wonder why they still had to deal with the same regressive attitudes, prejudices and all-round discriminatory bullshit as they did before.

In the late 70s and early 80s, black musicians were making an impact on the charts with soul and R’n’B but many young black Americans felt these serene sounds did not accurately reflect the difficult situation they found themselves in. When the art form of rap came along, which covered the harsh realities of urban life in simple spoken word terms, they latched onto it. When gangsta rap emerged – with its aggressive sound and meaning – as championed by Public Enemy and, later, N.W.A, it struck a nerve. N.W.A would ditch the more nuanced social message of PE and replace it by channeling the pent-up rage and frustration that was aimed squarely at the abusive authorities (and sell all the more records for it). Even for all its black pride posturing, the group would attract a white audience too with its mainstream, funky beat driven sound and reputation as the “world’s most dangerous group”.

[i[iframe id=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/7WiT-c3NA0M”]p>

Over the last decade and a half or so, LGBT representation has, across virtually all forms of media, not only grown exponentially but also matured. Gay characters have gone from being the ‘flaming’ homosexual caricature that dishes out gossip with Carrie Bradshaw to complex individuals who are no longer solely defined by their sexual orientation. There of course have been many gay artists, openly so or otherwise, to grace the mainstream before (Scissor Sisters, Elton John) but now we are seeing an increase in those who are willing to talk candidly about their experiences i.e. Sam Smith. There are also more gay artists who, relishing the increased presence, now willingly rock the boat and lash out at the perceived everyday homophobia they endure at a time when their lifestyle is supposedly becoming more ’acceptable’.

Perfume Genius is one of those artists but he’s not the only one. Bradford Cox, lead singer of the excellent noise-pop group Deerhunter, uses the homophobic abuse he has received as inspiration for the music he makes: The band’s debut mixtape Turn It Up Faggot, was even so named after the phrase was shouted at Cox during an early Deerhunter gig. As for the Trans community, up-and-coming dance/R’n’B prodigy Shamir is challenging gender norms by virtue of not having one. It’s still Hadreas, however, that bears the closest parallel to N.W.A’s cocky showmanship because, like them, he strives to be in your face about his controversial nature and this is especially apparent on 2014’s stunning Too Bright.

The first two records Hadreas put out mostly consisted of pretty and painfully personal, piano-led ballads but on Too Bright he became more extroverted and political, while making a greater effort to reach out to those in similar situations. N.W.A’s Straight Outta Compton, likewise, was an eruption of built-up anger and tensions to the extent that the group had almost nothing left to give – the Ice Cube-less follow up Niggas For Life may not have the same ferocity as the debut but it didn’t get the credit it deserved in its day.

The covers of both Too Bright and Compton display artists announcing themselves in provocative fashion. Hadreas, face previously blocked out on both his first two LP sleeves, is now fully visible in androgynous fashion on Too Bright wearing a skin-tight, sequined vest as he dons an impervious regal pose and begs to be looked at. While on the N.W.A cover, we see all the members in full ghetto garb looking down, directly and antagonistically into the onlookers eyes while Eazy-E, gun in hand, is about to shoot (it should be noted that this came at a time when risqué cover artwork could actually sell records). These were musicians who not only wanted to be heard but also seen.

The music itself is also designed to provoke. With a title like ‘Fuck Tha Police’, the controversy surrounding the song was always inevitable and made all the more scandalous when the FBI cautioned N.W.A’s record company about the inflammatory lyrics. If the gay population have their own ‘fuck you’ protest song akin to N.W.A.’s anti-authority smash, Perfume genius’s ‘Queen’ would probably fit the bill. The term ‘gay anthem’ can often be a patronising one as it’s usually reserved for twee Madonna and Dolly Parton cuts that have little to do with identity but here’s a genuine rally cry that might just deserve that title. In terms of sound, it marks a departure for Hadreas. It’s more poppy but also, with its move away from the piano towards synth-like electronics displaying a more diverse range from him than we’ve seen before.

Much of the song consists of Hadreas giving the naysayers exactly what that they want as he lists the over top and cruel stereotypes that are often afforded to homosexual men. The queen to be embraced of the song is a “ripped and heaving” bear as well as an aids sufferer who is “cracked, peeling” and “riddled with disease”. In one line – which comes about right before the heart pounding wordless chorus – Hadreas brilliantly sums up the baseless gay paranoia that can exist in middle class, Middle America: “No family is safe, when I sashay”, he sneers. When Hadreas performed the song with such confrontational lyrics in a ‘look at me’ white suit and bright red lipstick on David Letterman’s talk show, it’s probably a testament to the progress made that it wasn’t seen as a watershed moment (N.W.A never got the privilege of a live TV performance in their heyday). The video is equally as provocative.

[i[iframe id=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/S2Oqi8Ddqw4"]p>

It’s not only the overt kind of homophobia that Perfume Genius covers on Too Bright but also the more subtle, socially accepted kind. On ‘Fool’, Hadreas scornfully critiques the manner in which heterosexual women can use gay men as props. These are the kind of women we all know, the ones who sit in Starbucks and talk about the gay best friend they crave, not as a legitimate companion, but rather as a one-dimensional lap dog who can offer shopping advice or feign compliments. Hadreas is fed up of having to ‘Tither and coo’ for her “like a cartoon” or “bleeding out” unnoticed, “on the couch he picked out”. At the song’s interlude, he lets out a long heart-breaking wail presumably brought about by the pain he feels for being thoroughly used in a one-way relationship.

Both gay and black artists probably feel they have seen progress in their lifetimes but also a frustration at the slow pace of this progress. When we look at recent events in places like Charleston, Ferguson and elsewhere, there’s a sense of déjà vu- especially considering when contemporary rappers like Run The Jewels or Kendrick Lamar are covering the same kind of material N.W.A were in the late 1980s. And even when an artist like Frank Ocean – who has spoken openly about a gay relationship – is bridging the gap between these two types of artists, a certain acrimonious parking space incident involving Chris Brown shows have far we still have to go. Some things change and some things stay the same. At least, however, we can take solace in the fact there are musicians like this who are not only banging on the door, but willing to knock it down just to get noticed.