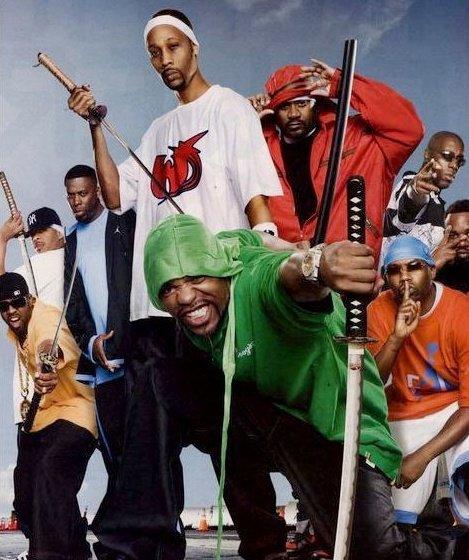

Wu Tang Style | Kung Fu metaphors & Black empowerment in the lyrics of the Wu Tang Clan

Straight Outta Compton, the raw bombastic retelling of the NWA’s rise to gangsta rap stardom took the world by storm critically and commericially. As a result, people all over the world have been reflecting on hip-hop’s journey from niche emerging genre in the 80s to its dominance of the mainstream musical landscape today.

With Straight Outta Compton‘s wild sucess we’re seeing some speculation about hip-hop biopics becoming a bigger genre within the film industry, with the sequel about the foundation of Dr. Dre’s Deathrow records already being shopped around. One of the most fascinating elements of the film for me was the way in which it articulated hip-hop’s utilisation as a voice for the voiceless in the African-American underclass, a barefaced representation of a reality hidden from the spotlight and swept under the rug, even as the drive-bys and drug deals existed in the same city as the glitz and glamour of Hollywood.

The usage of hip-hop as a revolutionary African American literary form has long been a subject of fascination for me and in the early days of hip-hop I find this best articulated in the work of the legendary Wu Tang Clan, the hip-hop supergroup that took the subculture by storm with their racous debut album; 1993’s Enter the Wu Tang (36 Chambers). On this album and the many sequels and solo works that would emerge from it, the various lyricists of the Wu Tang Clan made liberal use of references to Asian martial arts cinema, with the group’s name being derived from the 1983 Hong Kong martial arts film Shaolin vs Wu Tang. The album was peppered with samples from obscure martial arts films and would go on to be a signature element of records that fell under the Wu Tang umbrella.

The Wu Tang style was a natural outgrowth of the gangsta rap style popularised by West Coast groups such as NWA and the cerebral and metaphorical hip-hop growing up on the East Coast at the time which included legends like Nas and A Tribe Called Quest. Regardless of their varying levels of subtlety both styles wished to bring to impoverished and oppressed lives lived by many in the African American community at the time into the mainstream consciousness, shining a spotlight on the ghetto with insightful rhymes and slick beats. The Wu Tang exposé of African American life took the more metaphorical direction for which the references to Asian martial arts was essential. The members of the Wu Tang make continued reference to their home borough of Staten Island as “Shaolin”, one of the oldest and most popular styles of Chinese Kung Fu, closely associating the rigorous discipline of Chinese martial arts with the tenacity and toughness needed to maintain a life on the streets of New York City. The Wu Tang Clan view their perfectly honed hip-hop as akin to the reflexes and techniques of kung fu masters, used to fend off foes and protect the weak and powerless. RZA boasts of the Wu tang’s “360 degrees of perfected style” on Clan In Da Front emphasising the connection between the rigorous practice of martial arts and the Wu Tang’s careful craft of militant rhymes and beats.

This usage of martial arts metaphor to call for militant black empowerment is even more noticeable on Wu Tang Member GZA’s album Liquid Swords, which samples extensively from classic samurai film Shogun Assassin. The samples from the film link up with the austere, gritty production of the album to create an image of a New York city far from the pages of the New York times, a violent lawless dystopia with more in common with the rogue samurai infested world of Edo period Japan than the bright lights of broadway. GZA views himself and his hip-hop warriors as rogue samurai with honed blades and no masters to serve, seeking fortune in the lawless land of New York’s ghettos. GZA says his rhymes are militant tools of resistance as “I mic fights I swing swords and cut clowns”. The members of the Wu Tang see themselves not only as artists but as warriors who sharpen their weaponised rhymes at the whetstones of rap battles and then utilise the sharp wit of their serrated rhymes to hack away at the cosy white, middle class consensus of mainstream American music.

This usage of martial arts metaphor to call for militant black empowerment is even more noticeable on Wu Tang Member GZA’s album Liquid Swords, which samples extensively from classic samurai film Shogun Assassin. The samples from the film link up with the austere, gritty production of the album to create an image of a New York city far from the pages of the New York times, a violent lawless dystopia with more in common with the rogue samurai infested world of Edo period Japan than the bright lights of broadway. GZA views himself and his hip-hop warriors as rogue samurai with honed blades and no masters to serve, seeking fortune in the lawless land of New York’s ghettos. GZA says his rhymes are militant tools of resistance as “I mic fights I swing swords and cut clowns”. The members of the Wu Tang see themselves not only as artists but as warriors who sharpen their weaponised rhymes at the whetstones of rap battles and then utilise the sharp wit of their serrated rhymes to hack away at the cosy white, middle class consensus of mainstream American music.

The reference pool of the Wu Tang Clan’s work is wide, ranging from comic books to old school soul music, but undoubtedly their love for martial arts metaphors is one of the most vital and fascinating elements of their lyricism. In the disciplined, ass-kicking coolness of Asian martial arts cinema other ethnic minorities in America found an icon of resistance outside the white American mainstream. Cuban-American comic Joey Diaz talks about how the moment he first saw Bruce Lee dishing out furious blows in the Fist of Fury / The Chinese Connection was a “moment that changed America forever” and without a doubt the lyrical masters of the Wu Tang Clan would agree. The world of hip-hop would never be the same again and the African American underclass of the United States were sharpening their lyrical blades and perfecting their styles, ready to shine a spotlight on the deprivation of their lives with beats that struck like furious fists.

Featured Images:

theupperhandart.com

www.clashmusic.com

Rollingstone.com