YEEZY SEASON | Books, Beats, a Benz and a Backpack: How The College Dropout shaped the story of Kanye West

Kanye West releases his seventh solo studio record on February 11 (well, at least at time of writing that’s the plan) so it’s officially YEEZY SEASON. What better time to take a look back at his work to date? First up, Colm O’Regan sets the stage for the Greatest Rock Star On The Planet. It wasn’t quite so OTT back in ’04…

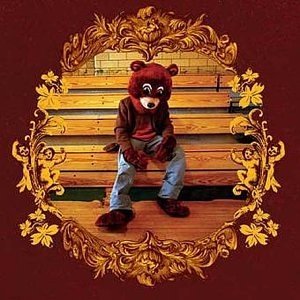

The College Dropout (2004)

Last month, the death of David Bowie saw one of the Internet’s more batshit theories reintroduced; that the cover of Ziggy Stardust prophesized the birth of one K. West almost exactly ‘Five Years’ hence. Obviously, the suggestion ranks somewhere between the earth being flat and RTÉ inventing Leitrim on the scale of what-the-fuck-are-you-talking-about, but it’s remarkable that the two artists are now, if not exactly bedfellows, at least comfortable inhabiting the same breath.

If an album cover in 1972 didn’t provide much indication, then there was almost nothing on the sleeve that landed on shelves 32 years later. There’s a bear – or at least some of one. It’s not a grizzly, or even an angry sun bear, but a slightly downhearted teddy-looking thing in jeans and one of your dad’s blazers. He’s sitting not on the mean streets, but on a set of bleachers, and framed – literally – by ornate, gilded detail. In the rap world of the time, ‘a departure’ doesn’t quite cover it.

And while his unequivocal response to Amber Rose suggests Kanye himself won’t be a fan of this, we’ve got to approach The College Dropout from behind.

To understand it, and its effect, you’ve got to remember the state of hip-hop at the time. The biggest stars in the previous year were Jay Z, still pushing tales of drug-dealing in Brooklyn, and the undisputed king of 2003’s rap game, 50 Cent. When they were respectively slinging rocks and getting shot, Ye was taking literature classes in a liberal arts college. As a journalist, I can attest that an English degree is no way to make a fortune, but nonetheless; while others were dying to get rich, here was a guy “with a Benz and a backpack”.

[youtube id=”YbWIbnjCaVM”]

You also have the fact that this guy isn’t a rapper, but a producer and writer told in no uncertain circumstances that his future lay on the side of the glass without mics. Whether that was down to doubts over his technical ability, as is often maintained, or the feeling that the Vuitton-tote-toting knob-twiddler would make for an uninteresting storyteller, is beside the point. The fact is that Kanye, even in the studio and as part of the Roc family, didn’t find it easy to have his voice heard. This, combined with his experience of turning away from formal education and the established way of doing things, informs much of the record. That’s not always a good thing – the laboured skits, perhaps palatable on first listen, soon land somewhere between irritating and downright infuriating – but the meat of TCD still hangs on those bones.

Take ‘We Don’t Care’, the first track proper, as a case in point. A few years later, it might have been delivered with vitriol, but as is could be called more disillusioned and disenfranchised than dissenting. The education system, government services, and life for the average Black American are all up for discussion, but none draw the sort of furious anger that defined later releases; instead, it’s with a wry smile and arched eyebrow that Ye makes his big-stage bow. A dyslexic kid whose favourite Fiddy song is ‘12 Questions’? Gold.

[youtube id=”8kyWDhB_QeI”]

The same pattern is to the fore on ‘All Falls Down’, where consumerism, greed and societal one-upmanship are skewered not with a frantic call to arms, but a self-deprecating confessional. Even the “you still a nigga in a coupe” line feels less a charged attack on racial inequality than a ‘what can ya do’ style shrug.

Make no mistake – Kanye isn’t happy. Hell, he’s a socially aware African American in Chicago; can you fucking blame him? But there’s a joy to this album, even when it’s at its most abrasive. Like life as a marathon runner, there’s pleasure in the pain; he’s laying out the struggles of minorities, the disadvantaged and the common man, but he’s pretty chuffed to be doing it.

That might point towards the most compelling aspect of TCD ten years on; the sense of paradox. It runs through the record like the writing in a stick of rock. It might not have the pointedness of David Foster Wallace pontificating on the great American Sadness, but ‘All Falls Down’ certainly sees Ye self-aware enough to recognise himself a victim of the same scourge he bemoans. “We ain’t letting everybody in our family business”? That’s on Track 19 of one of the most honest records in years. That’s followed by ‘Last Call’, one of the most sprawling, rambling and indulgent oral histories ever committed to record. It works as a parting shot, as the definitive guide to the artist who’s just produced a seminal record – though it offers little by way of a sign of things to come. For that, we have to press rewind.

The soaring ambition of ‘Spaceship’ – perhaps one of The College Dropout‘s most criminally underrated tracks – serves as an early indication of what we’ve seen in the interim. The stunning, arresting ‘Jesus Walks’ goes further. Everything from the economically challenged Midwest to what Jesus might – or might not – have looked like is tackled with relentless energy and unflinching bluntness and candor. It might be one of the few tracks on the album that could conceivably sit on most of his records and not seem out of place. When you consider how Kanye’s style, influence and musical direction shift with such regularity, that’s remarkable in itself.

[youtube id=”MYF7H_fpc-g”]

A large part of that, of course, is down to the beat, a haunting gospel choir sample allied with militaristic drums. Some critics of Kanye’s production style pointed towards its reticence to look forward; this was coming from a point of view where the futuristic sounds of The Neptunes and, to a lesser extent, Timbaland, were the driving force behind hip hop, and embracing the past was not the done thing. A dude with a bag of soul samples and a box of tricks was, as he’d done for Hova on The Blueprint, tearing up the rulebook one cut at a time.

Want an example? Listen to ‘The New Workout Plan’. No, it’s not a classic; it’s arguably one of the weaker efforts on show, and certainly the least lyrically substantive. But that low-end stripped straight from Chicago house, and the late handclaps, on top of that weird and wild violin? There’s three songs’ worth of things going on, and it’s deployed as little more than an extended skit.

And then, there’s ‘Through The Wire’. In this writer’s humble opinion, it might be the finest work of a blue-chip, Hall of Fame career. ‘But Colm,’ I hear you cry, ‘dude is mumbling!’ It doesn’t matter. And here’s why the song might be the perfect microcosm of the album, and the man. The story is true, and it’s damn well interesting. It might not be as rock’n’roll – or as R’n’B – as drugs or guns, but a near-death experience is a near-death experience. The telling is heartfelt, emotional and gilded by hope, as raw and riveting as it should be. Most of all, it’s a surprise. A guy who can barely flap his gums shouldn’t be in front of a microphone, much less delivering the rhymes to change his life forever. He sure as hell shouldn’t be making jokes about it. And who the fuck decided Chaka Khan should be getting in on this?

[youtube id=”uvb-1wjAtk4"]

But that’s the track, the album, and the man – at that point, at least. Brazen and occasionally brash; optimistic yet cynical; imperfect yet inspired; daring and defiant; harnessing the past to fuel his move forward. That it was the track to serve as his true breakthrough, the one to convince the powers-that-be to release him from the leash and let him have his day – and the one to announce his arrival to the listening public at large – is true poetry. The song, and The College Dropout, is the snapshot of Kanye 2004, with just a hint of where it might lead.