There is Nothing Exceptional about the Ana Kriegel Murder Trial Except the Verdict

In 2016 a 16 year old Argentinian girl, Lucía Pérez, met up with two men she thought were friends, who she thought she was going to hang out with and smoke some weed. They led her to an abandoned building, brutally raped her, impaled her and left her to die. Does this sound familiar?

Now, we have just learned the verdict in the Ana Kriegel case, in which she was lured to an abandoned building, by two boys she knew, brutally raped, beaten and left to die. Ana was 14. Her murderers, known only as Boy A and Boy B, were 13 at the time.

In Guatemala, my home for the last five years, an average of two women a day are murdered in circumstances not unlike Ana’s. It is not unusual to have at least one story a day of a woman’s dismembered body wrapped in plastic appearing in a ditch on the outskirts of the city.

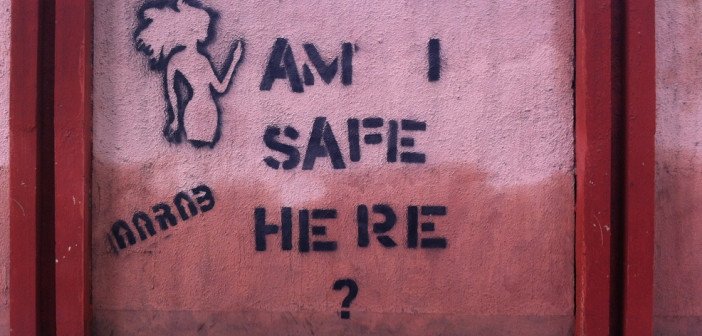

In Ireland we tend to consider ourselves as apart from the rest of the world. Perhaps it is because of our island nature, a tiny state on the edge of Europe, that has led us to believe that we are so exceptional. But there was nothing exceptional in the murder of Ana Kriegel. Her death is startlingly similar to the violence exacted against women across the globe. A violence, which, as the saying goes, crosses borders, classes and races.

A global epidemic of violence against women

Globally one in three women experience some kind of physical violence in their lifetime. Of them, one in five will experience a sexual assault. Again, Ireland is no exception, with national figures reflecting the global incidence. The statistics are well worn, trotted out every time the UN or NGOs publish glossy reports on any topic related to gender equality or, as now, when a woman or girl dies in violent circumstances.

Behind the statistics is the reality that we are immersed in a world that is still plagued by rape culture and the implicit acceptance of violence against women, where women’s bodies are considered little more than objects, or things, for male amusement, pleasure or power. A culture which creates the conditions for two boys to plan and execute the rape and murder of a 14-year-old girl.

The narrative of this case has been laden with the language of the exceptional: tragic, an aberration and unfathomable. It is all, but not only those things. Ana was targeted because she was different. She was an outsider. She was the victim of bullying that left her isolated and vulnerable. Much of that bullying centered around perceptions of her sexuality. Her murder was a cruel imitation of gorno movie tropes. One of her murderers, Boy A, apparently fetishised Russian girls. Boy B referred to her as a girl who wore slutty clothes. And in, the proud tradition of Irish court cases, the defense lawyers tried to attack her character with insinuations of promiscuity, which, in this case, failed roundly.

This case is a microcosm of the multi-faceted forms of violence faced by girls and women across Ireland and the world. It is a continuum. It starts with jokes and ends in rape or murder. Women and girls are targeted for their sexuality: sluts if we put out, frigid if we don’t. We are objectified and dehumanised through a rape culture that is ubiquitous in the media we consume, particularly on social networks. If we happen to be women or girls of colour, or in this case Russian or Eastern European, we are fetishised and dehumanised further. We are raped and murdered as men act out their entitlement and fantasies, get their revenge, exert their power over us, destroy our communities, or treat us as the spoils of war. If our case makes it to court we, or our families are revictimised, shamed and often blamed for the violence we experienced.

When I started writing this I thought that it was Ana’s age that makes this case exceptional. But young girls across the world are easy prey for sexual predators and Ireland, again, is no exception. So it must be the age of her murderers that sets this apart. It is certainly shocking to think that any 13-year-old could be capable of such horrific an act. It is undoubtedly one of the principal reasons why this case got the attention it deserved. The trial of minors for rape and murder is so exceptional in Ireland that special arrangements had to be made to facilitate the arrest and prosecution of the perpetrators.

Now that the verdict has been read, however, I would argue that the most exceptional aspect of this case was that Ana’s murderers were found guilty; the weight of forensic evidence and circumstantial evidence against them was just too much to deny. Nevertheless, after a quick scan of Twitter over the last few weeks it is clear that this was never a given. Many people feared, almost expected, a declaration of innocence.

Not One Woman Less

I have a weary sense of deja vu writing this. I write about sexual violence a lot. Since moving to Guatemala I have covered two trials relating to crimes against humanity where rape was used as a weapon of war and women were sexually enslaved. I have researched the weaponisation of gender based violence in forced evictions in Honduras and Guatemala. I have written about the mass murder of 41 girls in a fire in a state ‘care’ home, many of whom were survivors of abuse and while in care were subject to further sexual abuses and exploitation. Closer to home I have written about the Tuam Babies and the Paddy Jackson trial. What this has taught me is that there is nothing exceptional about violence against women, rather there are patterns, continuums, and more often than not, impunity.

I am not trying to downplay the significance of Ana’s murder. Quite the opposite, I am trying, instead, to argue that rather than seeing it as an horrific exception that lets us wring our hands for a few days, say a few prayers or light a few candles, her death should be understood as an aberration, one which is not separated from the national and global epidemic of violence against women.

When Lucía Peréz was murdered there were protests, marches and candlelit vigils that were driven by the Argentinian #NiUnaMenos movement. Three years have passed and #NiUnMenos has become a global rallying call to end violence against women and girls across the America’s.

In Ireland, over the course of the last three years, the Tuam Babies story broke, Clodagh Hawe was murdered and we had the Belfast rape trial. Now our country mourns the loss Ana Kriegel. Legal justice has been served, but a larger conversation in Ireland around bullying, consent and gender based violence is urgently needed. Perhaps we need to take to the streets with our own rallying call: #NotOneWomanLess. #NíLúBeanAmháin.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.