Welcome to Anyplace | Replacing Dublin One Hotel At A Time

Cathedral View Court was a literal name for the best part of its existence. The residents of this inner-city Dublin housing estate had a near-perfect view of St. Patrick’s Cathedral. They could see it from the street, their homes, their back gardens, almost anywhere.

“I’ve a little fella. We’ll he’d be your age now,” Lorraine, one of the residents says while fixing me a cup of coffee in her kitchen. “He’d often ring the bells in the cathedral. I’d stand out there and listen to them.”

As she recalls this, her neighbour Mary comes in to join us.

“It would be lovely, wouldn’t it Mary?”

“Oh Jesus, you could see the whole cathedral,” Mary agrees, jumping right into the conversation since she knows exactly what we are talking about. “I could look out my window, my landing, my bathroom. I could see the whole cathedral lit up green on St. Patrick’s Day. Lit up. You could see the people on the road, cycling, walking. It was lovely just to look at.”

“Ah it was. It was lovely,” Lorraine says. “Lovely, but sure you can’t see nothing now.”

“It’s gone. It was like we woke up one morning and it was literally gone.”

The pair are talking about a construction site that will eventually become another Maldron Hotel on the cityscape, towering over their neighbourhood and obscuring from view the Cathedral thus rendering the court’s name redundant.

Back in May 2016, the vacant lot on the junction of Kevin Street Upper and New South Street was acquired by the hotel group, Dalata for €8.1 million. Five storeys. 139 bedrooms. A restaurant, bar, cafe and basement parking. All of this and more by July 2018.

“The purchase of this property is a very exciting opportunity for the Company and is consistent with our stated strategy of securing development sites for further new hotels in Dublin,” a Dalata statement read promisingly.

“The Dublin hotel market continues to perform very strongly in 2016, and we look forward to this Maldron Hotel contributing significantly to the Company performance in the future.”

On the actual ground however, optimism was in short supply. Lorraine had recently put her house up for sale. It was valued at €450,000. Within two months, the price was €395,000.

“The auctioneer knocked on my door and said, ‘I’m sorry, but I have to put it down fifty grand,’” she says, stepping out into the backyard for a smoke. “I had to take it down on the 1st of December. There’s the For Sale sign,” she sighs, gesturing at the red plastic sign propped up against the wall.

Mary and Lorraine both lived here four decades. They guide me around their neighbourhood and see a future that promises fewer fond memories. Cathedral View Court is coated in dust. There are cracks on the streets and houses, which the pair insist were not there beforehand. The glass case for a Virgin Mary statue is yellow like nicotine stained teeth.

Mary brings me into her backyard, which is separated from the hotel by a wall and small laneway. A crane swings overhead. The scaffolding steals her light. All you can hear is the cacophony of construction, and when all of this is finally done, she will have half a hotel capable of seeing into her bedroom.

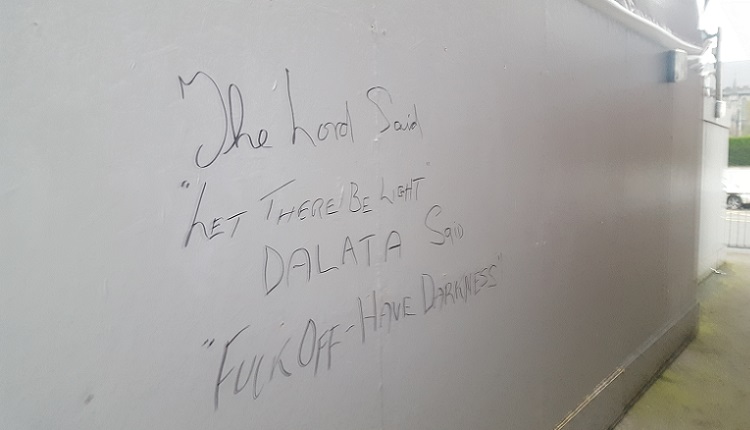

“The Lord said ‘Let there be light’ Dalata said ‘Fuck off – Have darkness,’” reads some graffiti scribbled on the wooden walls erected around the site.

Everyone already accepted that the hotel was not leaving. A neighbourly compromise was what they sought instead. The residents wanted to be treated as a visible entity. Their demands were simple; some form of compensation for the loss of light, privacy and parking spaces, a person to clean the area during construction, adherence to health and safety codes, and a surveyor to properly assess the alleged damages.

Sonya Stapleton, their local Councillor told me that compensation was unlikely. Such would set a precedent, she explained, which in turn would require Dalata to compensate residents down the line at other locations where they intend to expand.

With few options, the residents (many past the age of retirement) decided to take a stand. On a daily basis, they were out on the footpaths next to the hotel, stationed on the junction once nicknamed the Four Corners of Hell. It got that name in the 20th Century on account of the fact that each corner was occupied by a pub so you were always guaranteed a place to drink after Mass.

It appeared that hell was back, and its return was heralded by the signs hung on the picket-line: “New Hotel And We Get Hell.”

At the time, I reached out to Dalata for a comment, inquiring about the absence of a notice of planning permission for the addition of a roller shutter and pedestrian gate for the car park.

“The site at Kevin Street was purchased by Dalata with planning permission in a competitive tender process,” Dalata’s spokesperson wrote back. “The Group are fully compliant with planning and other regulatory directives. The public site planning notices have been correctly put in place at Kevin Street but are frequently removed. The site contractor is replacing these.

“Once construction is completed, the Group will have invested over €20 million in the area and will create over 100 jobs, many of which will be local. Dalata will be contributing to community development projects in the immediate area, relating to urban regeneration and landscaping.”

“A full prestart survey was conducted in accordance with regulatory requirements,” the spokesperson replied when I raised the matter of the demands. With that, they insisted no further comment would be given.

As the weeks went by, the protesters steadily decreased in numbers.

“Sure it doesn’t affect me,” one neighbour, Margaret told the few that remained, including Mary. “Terrible, I can picture what you’re going through. Jesus, looking at that and you wake up in the morning an’ ye look at that. But ye know what’d kill me? The people lookin’ out from there.”

“This is it, and they’re lookin’ in at us,” Mary replies.

“And nobody’s got a thing?” Margaret asks.

“Hittin’ your head off a stone wall,” a man says.

“Goin’ back years, the reason you got nowhere was because nobody ever stood together,” Margaret says, while turning to leave. “That’s all I can say, anyway. That’s all I can say to ye.”

“Okay, thanks.”

“Sonia had gone into a meeting with them,” Mary tells me. “She said to them to take off their business hats and put themselves in these people’s shoes. Ye’s are putting up a hotel and you haven’t even seen where these people live.”

Unfortunately this story fell off my tab for some time, but I knew where it ended. It ends with another hotel. That’s the only way these things seem to end now. Another place without any historical, cultural or geographical significance erected in a place once identifiable as Dublin. It became a non-place, to use the term coined by anthropologist Marc Auge. A generic construct that could be anywhere, in any metropolis.

It's with heavy hearts that we announce the end of our Bernard Shaw adventure. At the end of October 2019 we will close the Shaw, Eatyard, all organisational, art and performance spaces and everything else in the building and yards – for good.https://t.co/CGDpyluYIv

— The Bernard Shaw (@TheBernardShaw) September 9, 2019

It is the Starbucks on Drury Street which steals business from the small coffee houses that once owned the city’s Creative Quarters. Or the ever-increasing number of lifeless glass buildings that shoot up in the Docklands. Featureless hotels chip away at the identity of a place in order to ensure greater numbers can come admire the very thing being erased. The logical conclusion is a place where visitors cannot tell where an airport ends and a city starts.

And next up for the chop is The Bernard Shaw pub. A landmark that breathed life into the Dublin night, its fate the exact same as that which closed the Tivoli and Hangar. Out of the ashes come hotels. Maybe someone will honour the loss with a plaque someday, or include it on a rock ‘n’ roll guided tour. Scorch the earth, while celebrating the shamrock on some Carrolls keychain.

Welcome to Anyplace, Ireland.