‘Disobedient Women’ & the History of Body Hair Removal in Feminism

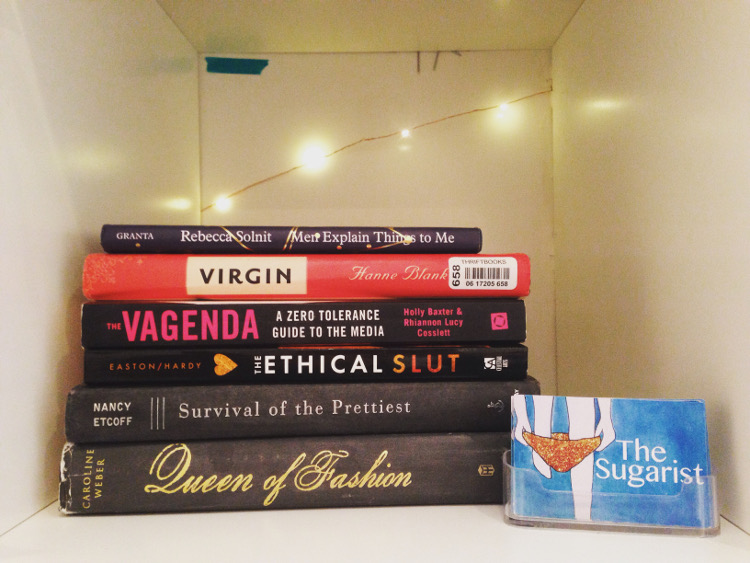

Sugaring, a method of body hair removal that originated in ancient Egypt and that uses a cooked paste of sugar, lemon juice and water, has recently regained popularity in the Western body-waxing scene. Lindsay Leggett, originally from Seattle, Washington, began sugaring in Ireland in 2013 and now owns one of the few salons offering sugar waxing services in Dublin.

In an interview exploring body hair removal and feminism, Leggett explains that grooming and adornment are “hard-wired” into us.

“The desire to appear attractive to our mates isn’t bad or wrong, nor does it mean we’re shallow. Although, telling us our appearance is the most important thing we have to offer, then shaming us for believing in and acting on it: that we save for women.”

A feminist who opts to forgo most body hair removal herself, Leggett claims that there are social implications for her choice that are indicative of the continuation of the association of body hair with radical feminism: “I haven’t removed my underarm hair since 1996 and I didn’t [shave] my legs for much of that time as well. It still surprises me how much that upsets some people. I think it’s because it’s one of the most visible indicators of a disobedient woman.”

Though various forms of body hair removal have been documented for centuries, it became a feminist issue in the 1970s when the Equal Rights Amendment coincided with the diminishing amounts of pubic hair seen in pornography and Larry Flynt’s Barely Legal, a pornographic publication depicting 18 year-old nude women.

Perhaps as a backlash to women’s acquisition of equal rights, pornography began to infantilise its models (e.g., the emergence of “school girl fantasies”), and fetishise a pre-pubescent look. Thus, feminism viewed the removal of body hair as indulging patriarchal standards of beauty and the synonymy of “submissive” and “feminine.” As a result, body hair became symbolic of feminist membership, while women who didn’t identify as such might have taken up shaving merely to distance themselves from radical feminism.

Commenting on the contemporary conceptualisation of body hair removal as a feminist issue, Leggett positions the phenomenon within its wider cultural and historical contexts.

“We in the West tend to think of body hair removal – especially pubic hair removal – as starting in the ’60s and ’70s with the advent of pornography when it actually began so long before that,” she says. “Not to mention that women in the Middle East, who may be covered from head-to-toe in burqas, begin removing their body hair at 11 or 12 years-old so, in this instance, I don’t know that we can say that this is for the ‘male gaze’ when men aren’t actually seeing it and men are also removing their body hair in these countries.”

A recent study of sexually-active women under 30 in the US revealed that 95% of the women surveyed either groomed, trimmed or completely removed their pubic hair. The prevalence of pubic hair removal would suggest that either a) feminism has been eradicated from the under-30 generation in the United States, or b) feminism is no longer associated with maintaining body hair. Neither is true. The maintenance of female body hair – armpit hair in particular – is still perceived as strongly associated with feminism or a political statement against patriarchy.

It’s more likely that body hair removal has become mainstream to the extent that a personal preference for hairlessness may outweigh a younger female feminist’s desire to adhere to performative displays of feminism. As a result, those who choose to go hairless can be subjected to social pressure and shaming within feminist communities, with one’s feminist integrity called into question.

Thus, the decision to maintain or remove body hair can become an issue of identity and group membership, rather than simply a matter of personal preference or the preference of one’s sexual partner (though the latter becomes complicated when one’s partner is male and his preference is for hairlessness, as it is then more easily framed as the accommodation of patriarchy; rather than if a female partner prefers hairlessness; or a male partner, a full bush, in his/her mate).

This prompts the question: under what circumstances is the decision to engage in body hair removal a matter of personal choice or a product of patriarchy?

Leggett, however, categorises body hair removal as another arbitrary “performative aspect of identity”; one that disregards women’s agency in their personal grooming and distracts from the more crucial aspects of the feminist agenda. She argues that, by focusing on trivial issues such as body hair removal, the feminist community is failing to address more important matters of equal pay, institutionalised sexism and maternity leave. “It’s a divisive tactic that’s used to splinter us, rather than dismantling the system,” she says.

Having previously been confronted about the discrepancy between her feminist identity and line of work, Leggett admits to reflecting on her professional motives and feminist integrity.

“I feel pretty strongly that removal of body hair is a moral neutral; something that’s important only in the context of a system (e.g. the Beauty Industrial Complex), that assigns value based on adherence to norms,” she says.

“That being said, I’m making my living off of the idea that hair-free is nice. In order to stay true to myself, I don’t use shame-based marketing and I don’t up-sell: if you come to me for your lip, I’m not mentioning your hairy chin unless you ask.”

Leggett’s clientele in Ireland “spans all demographics” and she estimates that her clients are 70:30 women to men, with male services – especially male bikini services – becoming more common.

In regards to gender and personal grooming, she notes the discriminatory nature of social criticisms of body hair removal.

“I think it’s very interesting that people never bring up men’s facial shaving: this is just accepted as a choice that men can make but women aren’t given that agency.”

Leggett is striving to distance body hair removal from its deeply-rooted associations with gender performance and traditional gender roles, as performative aspects of identity and group membership often inhibit personal choice and preference, and debates over such divert from the social and political concerns of greater significance faced by women.