Death of an Irish Town Revisited | The tragedy of Creeslough

“Is it hard to see death when it is disguised and tricked out in the surface trappings of life?”

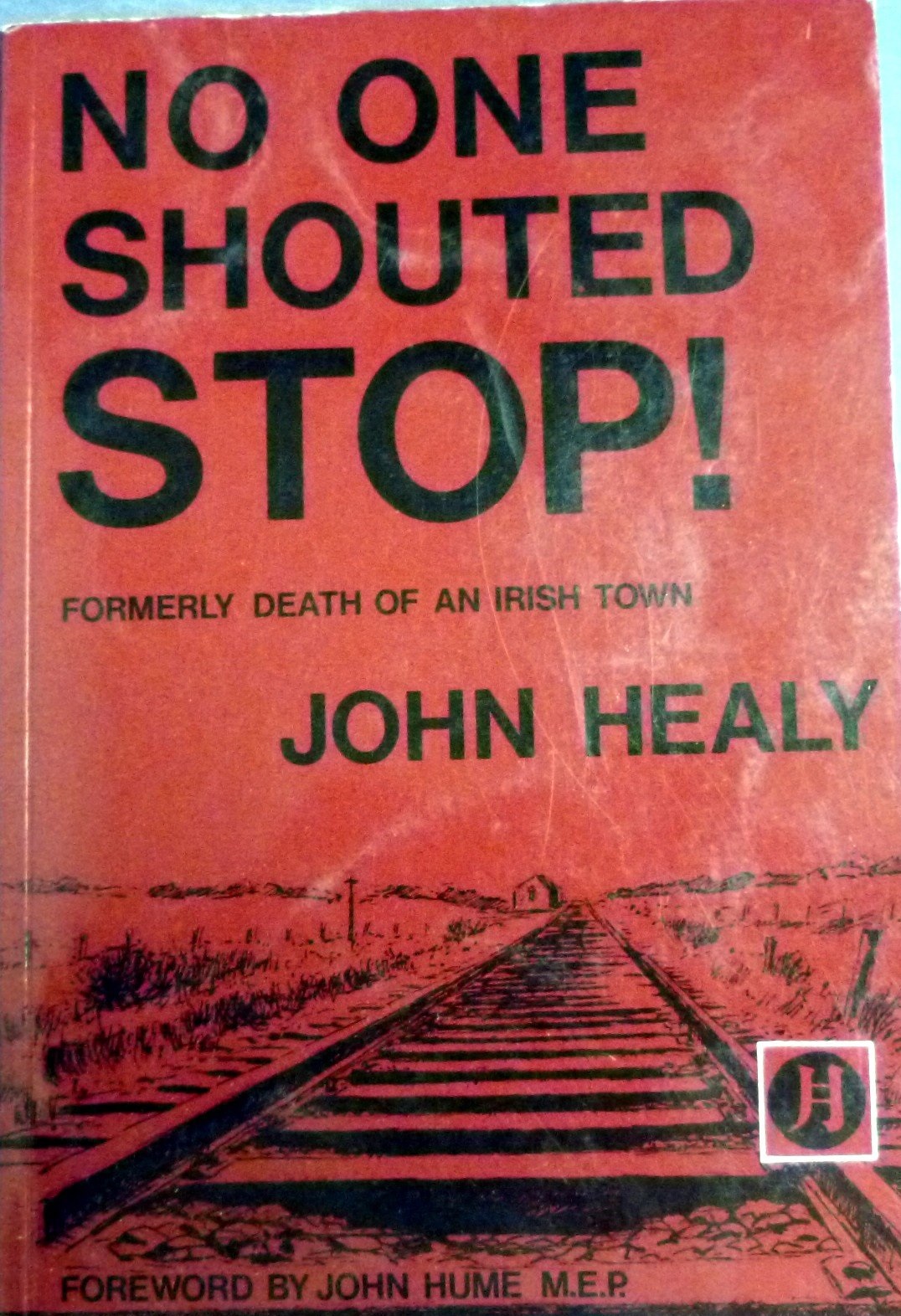

These words were written by a journalist named John Healy in 1967 in reference to the decline of his native Charlestown in Mayo over the course of the 1950s and 60s. Healy’s furious polemic on how the community of Charlestown was quietly and invisibly decimated by government neglect and much larger social and economic changes were gathered together and published as a book called Death of an Irish Town, which became an instant bestseller and talking point upon publication. You’ve probably heard of it at some point. Maybe it was mentioned in an Irish Times review of another book about rural Ireland, a retrospective on Irish life in the 1960s or even on a deeply awkward Nationwide piece on Charlestown where the host repeatedly reminded people of how it made the village famous.

Unfortunately, it’s a case of a book that is much more talked about or cited as a point of reference than actually read. It has all of 6 ratings and one review on Goodreads, despite being a book anyone with an interest in Irish history has probably at least heard of. Unlike a lot of such books, this isn’t due to its length or difficulty. For a start, it’s 96 pages long and can be read in a day with ease. It’s mostly a problem of availability, as it flits in and out of print. The first print run sold out rapidly, and there was such a long gap between editions that collectors were willing to pay 95 punts for a copy at one stage. The only page for the book on Amazon lists prices as starting at $39.97 for an ex-library copy of the 1987 reprint. John Healy himself is blessed with an author page that links to a different person.

Why then, is a book from the 1960s which it’s nearly impossible to get from anywhere other than a library’s reference collection still so famous and talked about? When I finally read it recently, I was struck by how little Healy’s writing had dated. Then, as now, the national media were parroting a narrative of progress and advancement which was largely centred around Dublin’s growth industries. Progress in the formerly impoverished Ireland was largely depicted in the media as being manifest in rising standards of living and drastic improvements in educational provision. John Healy’s writing caused a stir by daring to challenge this view. For Healy, statistics about car ownership and the construction of secondary schools in rural villages obscured the tragedy of the irrevocable decline of communities like Charlestown following a generation of mass emigration.

Only 3 people from Healy’s primary school class of 22 were still residents in the village, and entire townlands had fallen into disrepair. The lack of employment opportunities had led to the near-collapse of local sports clubs and dance halls, with other local businesses gradually but consistently closing until there was little left of the town and community of his childhood. The cultural and social life formed over the course of centuries had been quietly brought to the brink of extinction under the pressure of economic opportunity elsewhere and cultural shifts such as television at home, leaving a vacuum with little to fill it.

However, the book never descends into tedious polemic or providing another self-pitying rant about the forgotten people of the West. If that were the case, it would have been long forgotten about and rightly so. Healy’s anger resonates even now because he knows that the state of affairs he describes is not beyond redemption, and he finishes on a note of positivity by arguing that the extension of free secondary education to rural communities would make change possible. Change wouldn’t come from the top, but from within rural communities in the form of “People who will work. People who will provide leadership. People who will defeat apathy and indifference…People, who because they are educated, will demand as a right what is given to the less educated as a political privilege.”

This last passage was especially relevant for me. My family home is situated near a village named Creeslough in Donegal which has suffered a drastic decline of its own in recent years despite the best efforts of leading figures within the community to provide work and the resilience and dedication of the locals to fight to save it.

Creeslough may appear to the average visitor to north Donegal to be just another two-pub village with adjoining parish church and primary school nestled snugly into the stunning natural beauty of the landscape. It’s easily overlooked on the scenic drive to a holiday home along the coastline, and its population of 393 people fits into several Dublin nightclubs twice over. Spending time in either of the village’s pubs or church is the perfect antidote for a professional weary of a life of specialist doughnut shops and expensive coffee in the big city, as nothing truly worth doing can be done by halves. Former Guardian journalist and member of The Commotions, Lawrence Donegan admitted the pointlessness of a middle ground by moving to Creeslough from London for a year in 1998, publishing a memoir of the experience entitled No News At Throat Lake in 2000.

The book sold well and got good reviews, bringing relative fame to the village through mentions in newspaper reviews and occasional travel pieces. The main criticism which the locals had were that the author claimed to have changed their names when he hadn’t in best journalistic tradition. What strikes when reading it now is just how it stands as a record of a moment in time before the Celtic Tiger truly took hold in rural Ireland, insofar as it did at all through the explosion of the building trade.

Throughout the book, Donegan berates the crisis of mass unemployment in Donegal and the absence of any real efforts by government or the larger business community to alleviate it, and the subsequent loss of young people to cities in Ireland and elsewhere in the hope of a better life. Tragically, things in Creeslough have gotten worse despite the fortunes of the country at large over the same period. Much of this decline can be attributed to the collapse of local businessman Danny Lafferty’s business concerns.

Danny Lafferty was a local businessman who was amongst the few businessmen trying to sustain a local economy in Creeslough. At the time the book was written, he was the owner of a supermarket, a pub, a petrol station and the village’s hardware shop under the umbrella of Lafferty Enterprises. Some of these businesses had been in the family since 1906, and by 2013 they were employing 40 people. Lafferty Enterprises had not so much become Creeslough’s main employer following the collapse of the building trade, but the only employer. 40 people would barely cover the payroll of a McDonalds in a major city or the floor staff in Dicey’s, but it was nearly everybody save farmers working locally in Creeslough. Lafferty’s staff, and the village at large, were less his employees than his dependents.

This made the collapse of his family’s businesses during the recession the worst nightmare of a whole community rather than just a single man. Lafferty had little option after several years of sustained competition from the Aldi and Lidl shops which had begun creeping into small rural towns alongside the established retail sector of Letterkenny. It’s always hard to think of the small shopkeeper when you’re struggling to cover the bills even in Aldi, but the impact of people’s efforts to cut back was amplified by the fact that one in four people in Donegal were out of work by 2011. By the time Lafferty finally admitted defeat in 2013, his businesses owed a combined total of €1,232,809 to a variety of creditors. The rescue proposals put forward to creditors required some unsecured creditors to write off 95% of their debts. Unsurprisingly, this didn’t happen.

The locals did their best by Lafferty after hearing of his plight. By his own estimation, footfall in his businesses went up by nearly a third after he called an emergency public meeting. There were nearly a thousand people at this meeting, with the residents of townlands and villages across the area coming to show support.

This even managed to make an impression on the national press. It’s a cliché and an exaggeration to say that Donegal is the forgotten county, but The Sunday Business Post somehow managed to defy primary school geography by excluding it from a map of the border counties in a recent feature on Brexit. However, whatever coverage the case received in the national media mentioned the support shown by locals and the catastrophic consequences of Lafferty Enterprises going out of business.

Creeslough, by misfortune of not being a haven for tax exiles, was unable to sustain millions in debt with a tiny population and only minimal passing trade outside of the tourist season. Lafferty’s businesses closed, and their premises have lain vacant since. The situation has become so bleak that it made local news headlines when two of the premises went up for lease in January 2017. This tells you everything. The village has been so starved for hope that even the prospect of something, anything, moving in to create jobs is enough to create excitement and make headlines.

Nothing has moved in. Despite the much trumpeted “recovery”, the village’s surviving petrol station and adjoining shop still carry a sign beseeching locals and passers-by to “Shop Local and Save Our Village” as a grim reminder of how meaningless the good news stories from Dublin’s financial and technology sector are to those in dire straits. The decline of Charlestown repeated itself in our own time, giving Death of an Irish Town a grim resonance as small villages were overwhelmed by much stronger forces of multinationals and deregulation than existed in Healy’s time.

Despite this, the community refuses to die. The buses which carry people to work in Galway and Dublin are thronged with locals who’ve travelled for four or five hours after a hard week at work to see their family, work on the family farm, play for the parish’s football team and see their friends for a pint in the local again. They are joined in the mornings by plenty of people who get up very early in the morning to drive to work in Letterkenny or even further afield, often for minimal wages. It’s considered normal for people of all ages to drive great distances at their own expense to work for free, purely to get the experience which it’s impossible to get closer to home.

Even those who go to Britain or mainland Europe return as often as is affordable, flying home for such mundane occasions as First Holy Communions and County Finals. These people’s lives could be so much easier if there was even the possibility of finding work in their parish, and the hope of a better life without having to unwillingly go elsewhere for the opportunities city dwellers take for granted. There are dozens if not hundreds of villages around Ireland experiencing similar travails. Whilst each village may have found itself in such a situation for different reasons, they nevertheless are all equally in need of visibility in the media and support from government to survive. 50 years on from first publication,

John Healy’s book closed with a warning – “Who has failed us doesn’t matter. The crime of our day will be our failure to recognize the vacuum in rural Ireland – the vacuum in values and acheivements, of old and new heroes, the disintegration of a culture and a way of life – and how we will fill it, shape it and give it a healthy growth and future.”

We face the same challenge in our own time, as we approach the 50th anniversary of Healy’s warning. Do we allow history to repeat itself, reducing yet more rural Irish communities to consist of yet another generation forced to divide their time between several places, or do we learn from the mistakes of the past and demand genuine progress and investment that enables rural villages to sustain themselves and for people to realise their full potential there? Unless we do, we face the grim prospect of Death of an Irish Town still feeling as relevant as ever a half-century from now.