Empathy Machines | How can virtual reality change journalism?

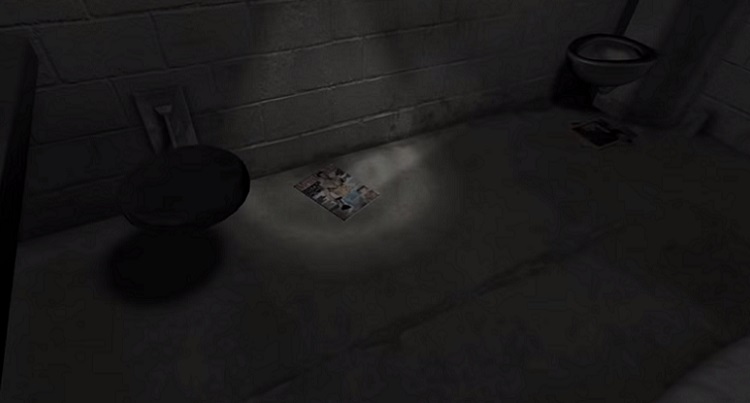

You are standing alone in a small cell, 6 by 9, listening to bangs and shouts echoing down the corridor. As you look around to get your bearings – a bed with a thin mattress, a toilet, a table screwed to the floor – you hear voices. They tell you what it is like to be locked in solitary for twenty-three hours a day. You might be put there for fighting with another prisoner, for drugs, for looking the wrong way at a correctional officer, for not eating all of your food. The speakers’ words appear on the walls around you. As the minutes pass, the walls crack and blur. You seem to be floating towards the ceiling. This is what it feels like, they say. Your mind becomes untethered; you can’t keep a grip on reality.

In 2016 The Guardian launched 6 × 9 – a 9-minute virtual reality film that was its first piece of ‘immersive journalism’. Built on testimony from prisoners, the film evokes the psychological effects of long-term solitary confinement. Two years ago 6 × 9 was an experiment in a journalistic form so new that its audience was still in its infancy. (For those without access to VR headsets, it can be watched on desktop as a 360 film.) But why is a gaming format becoming increasingly popular for news reports and documentaries?

One reason is that journalism has a lot of competition in the digital world. Consider the effect when US Senator Bob Menendez played audio on the Senate floor of crying immigrant children separated from their parents. It was a desperate appeal to conscience: ‘How do you submit the cries of innocent children into the congressional record? I don’t know how you do that, but you can hear it.’

The same week brought John Moore’s viral photograph of a 2-year-old girl crying while a US border agent frisked her mother. It was an instant and readable symbol of Trump’s immigration debacle that made the cover of TIME magazine.

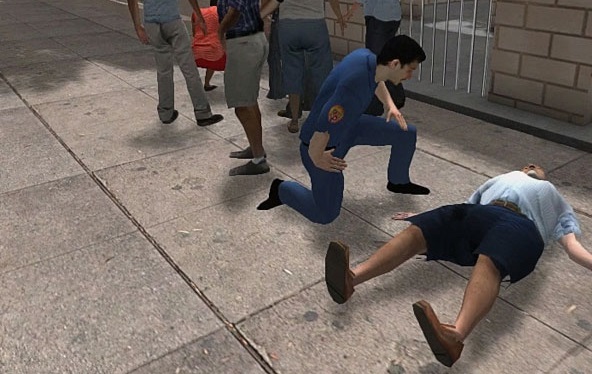

This was reporting that cut through the bluster of the American immigration debate. And these kinds of emotive stories are now driving immersive journalism. It was just 2012 when the journalist and film-maker Nonny de la Pe?a, ‘the godmother of virtual reality’, pioneered VR documentary with Hunger in Los Angeles. The interactive film combined audio recorded in a queue outside a Los Angeles food bank with CGI graphics. During recording, a diabetic man collapsed and paramedics were called. The effect is stark: a user in the VR experience is placed in the centre of the scene but is helpless to act.

This level of intimacy prompted film producer Chris Milk to dub virtual reality ‘the ultimate empathy machine’. His 2015 VR film Clouds Over Sidra, produced with the United Nations, follows a day in the life of a 12-year-old girl in a Syrian refugee camp. Other charities and NGOs have since followed suit: the hope is that immersive experiences do not just prompt empathy, but action too.

But for news outlets the VR opportunity is also about new audiences. The New York Times launched its NYTVR app in 2015 by sending free Google Cardboards to millions of subscribers. The newspaper followed up in late 2016 with the Daily 360 – trialling a stream of short 360 videos for browsers or smartphones – while PBS and USA Today have also produced VR documentaries. Though the audiences for VR and 360 video are still relatively small, in 2017 both AP and Reuters produced extended reports on the future of immersive journalism.

Yet while the audiences and the technology continue to develop, the most exciting innovations of immersive journalism are in its storytelling. 6 × 9 exploited the early insight that VR is particularly good at location-based stories. Total immersion is more powerful if the environment itself can tell a story.

The latest VR films are beginning to break with these conventions. The Guardian’s Limbo (2017) is a film about placelessness – a virtual experience of waiting for asylum. Voices of refugees guide the user through the experience of waiting for the Home Office interview that will decide their fate. This is a film about how it feels to arrive in an unfamiliar country, worrying about family at home; about the tedium and difficulties of living on £5 a day, and with a constant, grinding anxiety. This is a film about a state of mind, with a shape-shifting, dreamlike quality. That is, until you are sitting directly across from the Home Office interviewer and unable to answer his questions.

Limbo is an unsettling experience. It does not carry with it, of course, the months and years of anxiety and hope that have brought the interviewee to this point. The ‘empathy machine’ cannot bridge that distance. But it does ask the user to see this situation quite literally from another’s point of view. So too does Indefinite (2016) from the New York Times, a stark and striking film which follows the journey of detainees held in Immigrant Removal Centres while fighting deportation from the UK – the only EU country that allows indefinite detention. Though predominantly photo-realistic, it plays with the possibilities of its form. The roof of a cell gives way to blue sea as one detainee speaks of the despair of being incarcerated with no end in sight (‘they destroy your dreams, they destroy your family’). You are under water: ‘you feel like you are going to die’.

It was recently reported that the Home Office had mistakenly detained more than 850 people between 2012 and 2017 and has been forced to pay out more than £21m in compensation. All detainees were living in the UK legally. Can VR, ‘the ultimate empathy machine’, communicate their plight more effectively? Can it really shift and expand a user’s point of view? For all the technical obstacles facing VR film-makers, that will be the ultimate challenge of immersive journalism.