The Lesser of Two Evils | Secrecy versus Abortion

When an essay about my abortion experience was accepted for publication, I sat at my desk, chain-smoked and tried not to panic. Writing the essay was difficult and I’d worked hard; I should have been thrilled but instead I felt the cold hand of fear choking me. Was I ready to reveal the secret I’d harbored for decades to the world? Was it wise? Was it safe? Did anyone need to know?

Days later, to be positive, I mentioned the publication to my trainer at the gym, a guy known for his generous spirit. In the past, we’d discussed sticky topics like addiction and suicide, but when he asked what my essay was about, I froze, clammed up and blushed. My mind went into overdrive: Was this the place to talk about abortion? How would he react? Would he see me differently? Would he tell my fellow gym-goers? Would they judge me?

As I stood there, next to the free weights, stuttering, searching for words, he waited, and his expression changed from one of interest to confusion, even disappointment. I felt trapped. When you’ve been taught to keep a secret all your life, daring to even whisper it can feel like a violent threat to your being. So, I lied, or rather, omitted the truth – my default response. The exchange took about a minute. Then, I got on the exercise bike and peddled as fast as I could, as my mind continued to fire awkward questions at me: Was I wrong to assume he wouldn’t be interested? Why didn’t I trust him? I’ve known this guy for two years and he’s always been kind. Was I wrong to feel judged? Did I expect his support? Which was more important: his comfort level, or mine?

Today, safe and legal abortion is commonplace in certain countries. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) there are up to 50 million abortions each year. But talking about abortion outside political discussion is still taboo. “I don’t feel I’m not open about it,” a friend told me, adding that she felt is was “private” and that some of her closest friends didn’t know. She went on to tell me how she suffered afterwards even though she knew she made the right decision. Years later, she talked about the experience with her ex-partner and they both cried. Personally, I don’t think our unwillingness to talk about abortion has anything to do with privacy, but rather a wellspring of grief we have no idea how to express. We feel we’re not allowed to express that grief as we made the “choice” and therefore, brought the pain on ourselves. Worse, we feel the pain is deserved.[pullquote] I don’t think our unwillingness to talk about abortion has anything to do with privacy, but rather a wellspring of grief we have no idea how to express.[/pullquote]

As the days past, I had a new thought: I’m part of the problem – I have no idea how to talk about abortion. Despite writing essays that air my past to the world, telling people in my immediate circle was still terrifying. Before my essay was published, I worried for weeks about posting it on my Facebook page. When I finally did, the response startled me. I’d armed myself with abortion facts. I’d let go of my shame. I wrote the essay with the clear intention of criticizing the Irish government’s stance on abortion and decreasing stigma. I was ready for any negative comments. I was ready for a backlash. But there was none.

Three women commented; two told me I was brave, and another joined in the criticism of Ireland’s lack of legal abortion. That was it. My weeks of worry for nothing. Experience taught me my story is not unique or extraordinary in any way. In fact, it’s very ordinary. That’s what gave me the courage to write it: knowing how ordinary I was. I didn’t want or need sympathy or understanding, but I guess I’d naively hoped I might start a conversation. I was wrong.

In the run up to Ireland’s 2002 Referendum, I joined a socialist group campaigning for the “No” vote. We printed thousands of leaflets explaining the issues in an over complicated way (the reform which proposed the mother and her unborn had an equal right to life was complicated), and we stood on O’Connell Street handing them out. People ignored or insulted us. No one wanted to know. No one talked about abortion fifteen years ago.

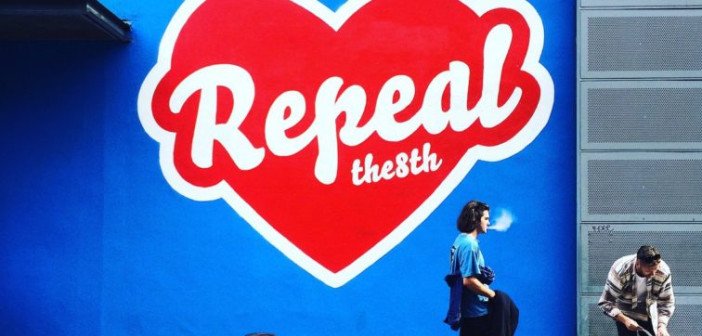

Since then, a generation has matured. There’s social media to facilitate a different kind of communication that brings together disparate voices. We have fresh perspectives that create projects such as The HunReal Issues, #shoutyourabortion and the Temple Bar Repeal mural. A recent poll by Amnesty confirmed that 80% of Irish people are in favor of scrapping the 8th Amendment. People are ready to talk about abortion; there’s more support. More Irish women have gotten on that plane. But where are their stories?

In December 2016 Lena Dunham hit the headlines again when she said that she wished she’d had abortion. The backlash was instant and severe. Her comment was labeled “distasteful.” Critics asked if she intended to “trivialize” abortion? She was forced to apologize and in her apology she said her goal was to “increase awareness and decrease stigma.”

My essay was published on the same day as Lena’s comments and I was shocked by the way women attacked her on Facebook, calling her stupid, insensitive, and a classic example of obnoxious white privilege. There’s no question that Lena’s guilty of saying some out-there things, but as Jill Filipovic pointed out in an article for CNN, should we really be attacking her unintended flippancy when we’re still failing to tackle some of the bigger injustices women face today? I think Lena’s comment tapped into something deeper: our unexpressed grief. Denial and anger are the first two of the five stages of grief. Our secrecy about abortion facilitates denial. Lena got a taste of our anger.

I have a dream: me sitting in a room with a group of people who’ve all experienced abortion. We chat to each other in a carefree way because there is no judgment in this room. Our regrets and hopes are different, but we are united by experience and grief. We share our stories. Some of us shout, others weep. After we talk, we hug and when it’s time to leave, we are smiling. Having shared our stories, the world feels less hostile. As I said, this is a dream. What’s real is the immense relief I now feel having published my story. Maybe someone will benefit from reading it, but I have benefitted because it gave me the chance to confront and accept years of pent up grief. And by confronting that pain, it’s given me the space to ask new questions about abortion.[pullquote]I now feel immense relief having published my story. Maybe someone will benefit from reading it, but I have benefitted because it gave me the chance to confront and accept years of pent up grief.[/pullquote]

Questions like: How much damage is this secrecy doing us? How are we ever going to get over the grief if we don’t express it? How can we expect governments to represent our needs if we don’t openly acknowledge this facet of day-to-day life? (Up to 125,000 take place every day, according to WHO). How do we teach our daughters to refuse to be judged if we don’t show them our strength? Look, I know I sound naïve but I believe our claims on privacy regarding abortion are counterproductive. I applaud Lena’s flippancy because we have to take some of the bite out of this gnarly topic. I believe women who have abortions should receive the same sympathy as women who suffer miscarriages. In part this belief stems from reading The Common Secret by Dr. Susan Wickland in which she posits that women choose abortion because they want to be the best mothers they can be.

Abortion forces us to question our lives, who we are and what we want, and for most of us, if we can avoid these questions, we will. Some people have clear ideas of what’s important to them and where they see their life going, but most people don’t know and struggle with major decisions regarding jobs, homes and relationships, taking time to choose the “right” option. The one thing a woman dealing with an unplanned pregnancy doesn’t have is time. She has to make a decision; it has to be now and it may affect the rest of her life.

This process puts life into sharp focus, forcing a review of values, what it means to be a woman, a mother and even a member of society. For years I couldn’t believe I was the kind of woman who would choose abortion, who wouldn’t want kids, under any circumstances. Today, I know different. Today, I know I chose abortion because I wouldn’t be a mother unless I was totally prepared, but it took me two decades to be at peace with that reality.

Having talked to dozens of women about abortion, this is often where their regret stems from: “I wasn’t prepared.” “I just couldn’t do it again.” “I didn’t know how I was going to survive.” They saw abortion as a failure of womanhood but what if we saw it as a triumph of responsibility? What if it was okay to talk about abortion as part of daily conversations at the gym, hairdressers or office, in the vegetable aisle at the supermarket, on the street, in pubs, at the dinner table?

What kind of world would that be? Imagine being able to confide in your boss. Imagine employers paid for the procedure. Imagine funerals for our unborn children. Imagine the closure. Do you know what scares me more than abortion? A future of secrecy that silently torments legions of women and paves the way for on-going stigma or lack of safe services. For now, abortion remains an intensely private issue, so I can only speak for myself. The next time someone asks me, I will not flounder, I will say yes, I’ve had an abortion. Actually, I’ve had three.