Is This The Modern World?

‘Modern’ is a word of soapy slipperiness that means different things to different people. The values it carries vary too; for some, seeking to be modern is an inherently noble aspiration while for others the very word is an insult.

It’s a word I’ve been thinking about a lot, lately; pictures, portraits of experiences, snapshots of encounters with the modern, with modernity, keep coming to mind. Thrown together they form a mosaic that might help to illuminate what ‘modern’ actually means. Or perhaps they’ll just form a useless, haphazard pile. But let’s go with the Modernity Mystery Tour anyway.

The Enlightenment

A good few years ago I found myself at a gathering of literary folk. Discussion turned to the then-approaching Scotland’s Year of Homecoming, 2009 (à la The Gathering). The feeling of the meeting, or at least of those who spoke out, was that it was A Bad Thing. One lofty-sounding gentleman attacked the proposed programme largely because it didn’t focus on his own particular hobby-horse. ‘There’s nothing about the Enlightenment,’ he wailed, ‘why aren’t we celebrating the writings of Hume and Smith, the way they shaped the thought that created the modern world? I see Enlightenment thought as Scotland’s greatest historic achievement.’ There was some sage nodding at this amid the more general bafflement.

A good few years ago I found myself at a gathering of literary folk. Discussion turned to the then-approaching Scotland’s Year of Homecoming, 2009 (à la The Gathering). The feeling of the meeting, or at least of those who spoke out, was that it was A Bad Thing. One lofty-sounding gentleman attacked the proposed programme largely because it didn’t focus on his own particular hobby-horse. ‘There’s nothing about the Enlightenment,’ he wailed, ‘why aren’t we celebrating the writings of Hume and Smith, the way they shaped the thought that created the modern world? I see Enlightenment thought as Scotland’s greatest historic achievement.’ There was some sage nodding at this amid the more general bafflement.

Then the conversation took another twist; someone argued, passionately and angrily, that the Year of Homecoming was a bit of cheek on the part of the Scottish nation. After all, the ancestors of the people now being invited back had very likely been hounded out of the country during the Clearances, Lowland agricultural improvement, periods of unemployment and poverty, or perhaps after Jacobite intrigues and rebellions. Why would they want to come back to the country that expelled their forebears? Didn’t we have a nerve to even be asking them?

This got a good reception, including from Enlightenment Guy. It seemed to escape him that the agricultural improvers, the architects of the Clearances, they were Enlightenment men. They brought the spirit of rationalism, of science, to the management of their estates. They believed that the way these tracts of land were run had to be modernised as, indeed, did the archaic clan system in the Highlands. Outdated practices, inefficient uses of the land, had to be swept away. If that meant that people – their tenants – had to be inconvenienced, relocated, or perhaps burned out of their homes and forced to emigrate to Canada, so be it. It’s the Enlightenment, mate. Get modern.

Football

The ‘M’ word crops up in a completely different context as we view another snapshot. Here, I’m seven years old and reading my Scottish Football annual covering the 1966-67 season. It had been a good year for Scottish football; Scotland thumping England at Wembley with Jim Baxter playing keepie-uppie, Celtic winning the European Cup and all that. The author of the introductory chapter was the then doyen of Scottish football writing, Hugh Taylor, and his theme was what he called ‘Modern Method’ football. It wasn’t just Scotland’s new Wembley Wizards, or Celtic; it wasn’t just Kilmarnock and Rangers (who’d also had good Euro runs) but teams at all levels of Scottish Football who were now examining their style of play (unexamined football not being worth playing, as the boy Socrates might have said), and playing scientific, structured football. Coaches steeped in what would soon be called Sports Science were, you could say, bringing rational, objective Enlightenment thinking to the beautiful game.

In fact, in that legendary Lisbon Lions European Cup Final, I think that it was Inter Milan who were applying ‘Modern Method,’ in the form of their strict, defensive Cattenaccio system. Celtic untangled it not with arid, objective stuff straight off the scientific press, but with auld-fashioned Scottish fitba that featured dribbling and darting runs and quick passes and lots of energy and aggression. Nowadays the Modern Method is still with us, with ‘anti-football’, dreary one-up-front formations and the talent of Mourinho, the Special One, for winning ugly.

And so to another picture; it’s me, reading again, but in much more recent years. I was once a subscriber to the Christian think-mag Third Way. In the late 1990s I began to grow uncomfortable with it. I found that I was starting to give up on articles whenever they used the terms ‘post-modern’, ‘post-modernist’ or ‘post-modernism’. By the early 2000s, therefore, I was giving up on most articles just a paragraph or two in. Shortly after, I just gave up on the magazine.

Architecture

The term ‘post-modernism’ is said to have first arisen within architecture; it was less a reaction to modernist architecture itself, than to its dogmatic insistence that architecture that wasn’t modern was rubbish and ought not to happen. Post-modern thinking spread throughout the arts and culture like a PC virus. Dogmatism in any form – insisting that some of the arts were ‘higher’ than others, believing in religious truths or political certainties – was regarded as bad, ill-mannered and, in general, thoroughly to be condemned. Objectivity and empiricism, the Enlightenment virtues, got a kicking, because all objective truth, all fact, all reality, was socially-constructed.

The term ‘post-modernism’ is said to have first arisen within architecture; it was less a reaction to modernist architecture itself, than to its dogmatic insistence that architecture that wasn’t modern was rubbish and ought not to happen. Post-modern thinking spread throughout the arts and culture like a PC virus. Dogmatism in any form – insisting that some of the arts were ‘higher’ than others, believing in religious truths or political certainties – was regarded as bad, ill-mannered and, in general, thoroughly to be condemned. Objectivity and empiricism, the Enlightenment virtues, got a kicking, because all objective truth, all fact, all reality, was socially-constructed.

So for a while, Modern Man and Woman were actually post-modern, self-referential, eclectic, inclusive yet ambiguous. Of course, the party-pooper could point out that in literature, some writers had been blurring the distinction between fiction and reality, between the writer and the written, for hundreds of years, long before the feted post-modernist authors of the 1980s and 1990s. And, anyway, in the second decade of the 21st century, extreme certainty is making a comeback with the resurgence of fundamentalism in many forms.

At one level, to be ‘modern’ is simply to be up with what’s happening, Daddio; recognising what’s the latest in fashion, in music, in art, in belief or unbelief, in popular causes and movements. Yet that kind of modernity comes with a heavily-stamped sell-by date; think of those documentaries with slappable ‘cultural commentator’ talking heads who chortle at 1970s fashions or 1980s music. These same people wore those fashions and listened to – or wrote – that music, believed in it, and were so hip they squeaked for doing so. What’s sparklingly modern today gets chucked in tomorrow’s recycling bin. Just think how Lady Gaga’s egregious outfits and headgear will be derisively hooted at when they feature in nu-nostalgia programmes ten or twenty years hence (or perhaps they are already?).

You can also be modern if you’re aware of, involved in or perhaps contribute to cutting edge research and debate in the sciences, in philosophy or other rarified academic discourse; any worlds, in fact, where they actually use words like ‘discourse’. Of course, only a few, select, extremely large-brained individuals can ever be ‘modern’ in the sense of being able to understand the latest subatomic particle activity in physics, or alert to the latest positions of Structuralism, Post-structuralism and the rest in the literary criticism league table.

But modern science is a doddle compared to the steamy, controversial and provocative world of modern art. Must Modern Man or Woman be a stout and hardy traveller in the world of wacky conceptual or installation-based art? Of course modern art extends far beyond the showpiece, Saatchi-endorsed stunt art that gets lots of coverage because it happens in London, a lazy taxi ride from the BBC studios. Genuine, talented artists are still working, emerging from colleges and art schools, exhibiting on graduation and afterwards, displaying all the ability, vision and imagination of artists down the centuries, yet in fresh, new, exciting, stimulating, modern ways; and without any unmade beds or tacky diamond-encrusted skulls in sight. Are truly ‘modern’ folk aware of this, are they unswayed by the sensationalist arts coverage on telly and in the papers? Perhaps, but then they are simply demonstrating the qualities of intelligent, sensitive people of any age.

And this raises another snapshot from the past; as a primary school child, I spent a couple of years in Glasgow, in Dennistoun, and attended school there. Once a week, our class travelled in a hired bus to Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, where we descended to the education room deep in the basement of the building. We were given a short presentation about minerals or dinosaurs or mummies or suits of armour and were then let loose with worksheets to learn from the exhibits themselves.

They were a canny lot, the museum staff; the city’s renowned art collection was housed on the top floor. We’d shown no indication of wanting to go and see it, wee Glesca scallywags that we were, but the museum staff were careful to urge us not to go to the first floor. We weren’t allowed to see the art. It was forbidden. A few weeks into term, though, they suggested that if we were good, if we worked hard at the next couple of sessions (on mammals or fossils, perhaps) we might be allowed to go and see the paintings and sculptures.

Art

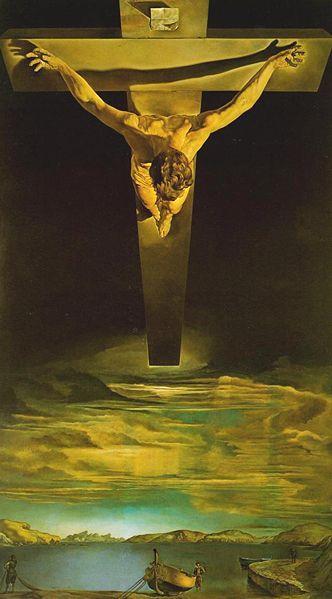

So those clever people not only had us desperate to see the art, and convinced it must be exciting to do so, they had manipulated us into believing that being allowed to see it was a treat; like going to the seaside for the day and being handed an ice cream with a flake. When we were finally unleashed on the top floor, I remember running up the stairs to find out what was there. And I don’t think any of us were disappointed; Rembrandt’s Man in Armour and Dali’s Christ of St John of the Cross and Degas’ Jockeys in the Rain. But we also got into a gallery that was exhibiting some modern, abstract works. Inevitably a few were a bit puzzling, but there was one painting, (which I’ve never been able to find since) called No Way Out that consisted of crude coloured shapes arranged in a claustrophobic pattern, with the words ‘no way out’ squeezed into a narrow interstice near the centre. I saw it just the once, but the sense of despair and incarceration remains with me still. My pals were affected by it, too, ordinary working-class nine-year-olds just like me. Were we ‘modern’? Or were we just open and receptive to art, whoever had made it, whenever it had been constructed?

So those clever people not only had us desperate to see the art, and convinced it must be exciting to do so, they had manipulated us into believing that being allowed to see it was a treat; like going to the seaside for the day and being handed an ice cream with a flake. When we were finally unleashed on the top floor, I remember running up the stairs to find out what was there. And I don’t think any of us were disappointed; Rembrandt’s Man in Armour and Dali’s Christ of St John of the Cross and Degas’ Jockeys in the Rain. But we also got into a gallery that was exhibiting some modern, abstract works. Inevitably a few were a bit puzzling, but there was one painting, (which I’ve never been able to find since) called No Way Out that consisted of crude coloured shapes arranged in a claustrophobic pattern, with the words ‘no way out’ squeezed into a narrow interstice near the centre. I saw it just the once, but the sense of despair and incarceration remains with me still. My pals were affected by it, too, ordinary working-class nine-year-olds just like me. Were we ‘modern’? Or were we just open and receptive to art, whoever had made it, whenever it had been constructed?

And so to a final picture; growing up in any British working-class home in the sixties you learned what a cherished aspiration it was to have a ‘modern’ kitchen, a ‘modern’ lavatory, or a ‘modern’ unit for the telly. One of our treats of the year was to go to the Modern (that word again) Homes Exhibition at the Kelvin Hall in Glasgow to see all the latest furniture and decorative schemes that we couldn’t afford. But our favourite Sunday afternoon family excursion was to dress up semi-smart and walk over to one of the new private housing schemes that were spreading like acne around town, and visit the showhouse. We’d coo at the bright modern exterior, the open-plan living room and kitchen and, of course, marvel at the modern furniture and fittings.

By contrast, remember blue-blooded Tory Alan Clark’s withering comment about his new-money colleague Michael Heseltine? ‘The trouble with Michael is that he had to buy his own furniture.’ Clark was being old-fashioned and snobbish, albeit in a viciously amusing way. But we craved the new – if cheap – and bright in order to make the homes we lived in more appealing, more welcoming than they’d been in the gloom of wartime and subsequent austerity. Were we being modern or just naff, undiscerning, lacking in proper taste? Most of my older family members had left school at 14, so I’m not sure where they were supposed to have learned ‘taste’.

My sympathy here is with ordinary people and their understandable desire for the new, clean, bright and simple. For a sense of it, watch ‘The Cistern’, an early episode of On the Buses, which delightfully shows forth the joy of acquiring a new toilet suite for working-class people who not long before wouldn’t have had a toilet of their own at all. No doubt, if their area had later become gentrified, they’d have been posthumously castigated for ripping out the toilet’s cast iron predecessor complete with dangling metal chain; imagine removing their original features.

So, in 2014, must you be able to cite the latest music trends, name the latest of London’s pet artists, explain the latest findings of the Large Hadron Collider, or understand how the latest abstruse literary theory has further diminished the status of the author, in order to be seen as ‘modern’?

Certainty

I’m not sure. I hope not. But if I was Modern Man, I’m sure I would know, with an alarmingly dogmatic certainty.