Writing, Literature and Tautology: Dismissing the Grammar App

“He slept curled up on the hard rock more soundly than ever he had done on his feather-bed in his own little hole at home. But all night he dreamed of his own house and wandered in his sleep into all.”

We need to talk about the word “own”. As you can see from the above, a short excerpt from Tolkien’s The Hobbit, “own” can be used as an adjective. To function as an adjective, it must be placed with a possessive – my, his, her, our, etc. The use of “own” in this way is designed for emphasis. If the sentence had read, “he dreamed of his house”, the meaning would remain the same, but putting “own” in there gives the sense of ownership a little more strength.

We might also add – and this could be a subjective opinion – that in the case above “own” also adds some subtle strength to the sense of longing in the sentence. When you speak with a friend after a trip, perhaps after a long flight, you might say, “I can’t wait to get into my own bed.”. This serves the same purpose: “own” is doing a bit of subtle work to emphasise ownership and, maybe, the sense of longing for one’s bed.

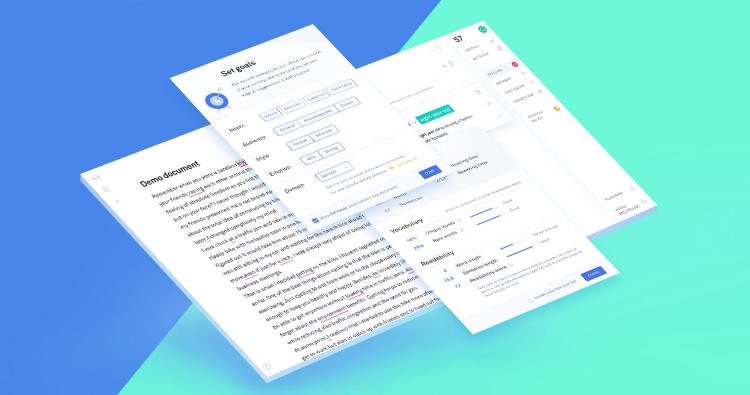

So, why talk about this at all? Well, grammar apps, which many of us are using these days, take exception to “own” as an adjective. It’s considered a grammatical tautology or redundancy. In the eyes of the software, ownership is already implied by the possessive, so it will prompt you to remove the offending “own” from your sentence.

Grammar software pursues brevity

If Tolkien were to have written The Hobbit using a grammar app, he’d see lots of blue and red lines throughout his text. Despite being a master linguist, Tolkien wasn’t what you would call a grammarian, but that’s beside the point: tautologies have a place in writing, as do many other ‘mistakes’ picked up by grammar apps.

At the heart of the grammar app’s modus operandi is the relentless pursuit of conciseness that it sees as a means of achieving clarity. But a tautology, for instance, isn’t confusing. We know what people mean when they say “global pandemic” or “black darkness”. Literature’s most famous tautology, Hamlet’s “To be, or not to be”, isn’t confusing in its meaning. But the grammar app – and grammar pedants – take exception to it. Why? Because brevity is better in their eyes.

The grammar app will also pick up on words that it deems redundant. If you were to write, “the woman was clearly ill” or “the man was obviously insane”, most grammar apps will suggest that you remove the adverbs “clearly” and “obviously” as they are flagged up as redundant. Most people reading those sentences would beg to differ, of course. If a woman is clearly ill, it is suggestive of a visible illness, whether physical or psychological. If a woman is merely ill, we do not know whether the symptoms are visible or not. In this sense, the grammar app’s pursuit of brevity might lead the author to diverge from their original course; to say something they did not mean to say.

Shades of Orwell’s Principles of Newspeak

The quest for brevity is also present in one of literature’s most famous linguistic constructs, Orwell’s Newspeak. Now, we are not saying that the builders of the Grammarly or Hemingway Apps are trying to subvert the individual’s ability to think as were the goals of Newspeak’s creators in 1984 – of course, they aren’t. But simplifying – or oversimplifying – language matters.

Of course, the grammar app does not force us to delete these words; it merely suggests. We can dismiss the suggestion with a click and forget all about it. But there is a greater truth here. Namely, the grammar app markets itself as the right way to write. And many people will believe that the technology is a better judge than their own good sense.

Technology gives us instant gratification. If I wanted to watch the 1974 FA Cup Final, I could easily find the footage on YouTube in seconds. If I click here, I could instantly spin a roulette wheel as if in a real casino. If I want to hear Bizet’s Carmen, I simply have to pick up my smartphone. But tech also gives us instant knowledge, or at least we believe it does. We can ‘google’ anything and find instant answers, eliminating the need to debate or work out the solution. Of course, there are many things we don’t know, and searching for knowledge is a good thing. But we have been conditioned to think that technology has all the answers, and that’s not necessarily true with language. At least, it’s not true yet.

Grammar apps are certainly not without merit. Even the best of us can overlook a “their” and a “there” when performing a proofread. Indeed, it would not be surprising to see a typo or two in this text. But there is – let’s say – a sanitisation of language performed by the software, and that should be viewed as problematic.

The heart of the problem is that the software does not know for whom your writing is intended. Tolkien would have written a CV in a very different style compared with The Hobbit. As a matter of fact, The Hobbit’s grammar rules differ somewhat from those Tolkien used in The Lord of the Rings. Nevertheless, the software tends to assume that your writing will be read by a human resources manager rather than a literary editor.

That’s fair enough, given that these app creators are in the business of making money and will know their target audience. But the fear is that children – or anyone learning to write – assume that the grammar app rules are the only rules. The technology is likely to improve over time, and we should not be dismissive of that – perhaps one day the grammar app will be a better judge than the writer. But for the moment, the best rule of thumb is this: If you are writing a CV or some other ‘dry’ business-related text, pay heed to the grammar app. If you are writing to enchant, please or delight, then clearly it’s best to play by your own rules.