Why time feels really strange on holidays

We all know time can feel slow and long when we stew in boredom, or rush past us when we’re excited and enjoying ourselves. Sometimes though, it’s not so simple. Sometimes we feel the same patch of time as both short and long at the same time. The most common way people experience this is on holidays.

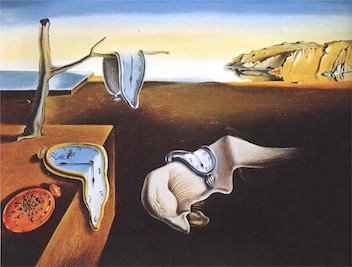

So, let me give an example. I was away in Lisbon over the summer and – I don’t want to be one of these people who goes on and on about their wonderful holiday – but oh my god it was amazing. I mean one day me and three friends went to a huge Knights Templar palace – it looked like the Disney castle re-designed by the Adams family – in a vast estate dotted with hidden passageways. While exploring these we lost our friend Dee, until we finally found her, giddy and laughing at the bottom of a giant ‘initiation well’. That night we tried to get into John Malkovich’s nightclub, and were refused entry unless we paid €250 each (henceforth I will never be able to look at his acting without my face contorting into a snarling grimace). Hours later at a beach bar my friend Dave said ‘It’s so weird, yesterday we were in Dublin’. And we all laughed at the strangeness of it, and laughed like we’d never again be caught in Dublin’s grey rain since time was stretching now, like melted, gooey cheese, and maybe it would just keep going.

The strange feeling we had was that in one way time felt fast – exploring the palace and going to the club had all sped by me, so that every time I’d checked my watch that day I was surprised at how late it was. But then when I remembered the whole day, time stretched out and expanded. It felt like 3 days since I’d left Dublin, not just one. Look at the day one way it’s short, and the other way, it’s long. I always think of it as ‘trombone time’. So why does it happen?

This phenomenon – known as the Holiday paradox (1) – is a fascinating subject in the psychology of time perception, as this ‘glitch’ reveals a wider contradiction in how we perceive time. How we sense time is far more complex than you’d imagine, with no clear consensus on how our brains can record, measure, and judge time durations (2) (a great intro to time theories can be found in Claudia Hammond’s Time Warped).

We perceive time in two different ways: prospective duration is how long time feels while we’re in it, and retrospective duration is how we feel time has passed when we remember it. There’s been a host of experiments to discover the differences between these two. For prospective time, subjects are given a task and told to keep note of the time, so they give answers showing time as it’s felt. For retrospective time, subjects are simply given the same task and then surprised afterwards with the time question, giving a sense of time as it’s remembered. You wouldn’t imagine there’d be much divergence between these two, but there’s consistently a large gap between them.

Prospective Time (how it feels when we’re in it)

One way to stretch out prospective time for someone is to give them a very boring task. Tell them to go wait in a queue, do some simple sums, or watch a kettle boil and they’ll report a long time period. If you want to shrink prospective time, give them something really demanding and mentally engaging to do, like a complex puzzle. They’ll then report a shorter time period than what occurred. If you include a ‘rule change’ in that puzzle, so they have to reorient themselves half way through, the time will shrink even further. The more complex distraction you can get in there, the shorter time feels. For example, subjects reading text with difficult formatting, which they have to engage with to interpret correctly, report 49 seconds as having lasted 24 (3).

So, in Lisbon – I was seeing a lot of new places in one day, exploring different areas full of novelty, and dealing with my deep disappointment in an unbelievably shoddy actor who I used to respect (€250, seriously now). I was really ‘plugged in’ – my mental activity was high, and the context of my actions was changing almost every hour, so that time was moving rapidly as my mind played catch up with my surroundings.

Retrospective Time (how we remember time)

This is where it gets a little weird. Everything flips. If you give someone the same boring tasks – basic sums, wait in a queue, watch a kettle boil – they’ll remember that time as really short. If you give them a complex and engaging task to do, a puzzle that needs them to ‘switch on’ mentally to solve, they’ll report a longer time. If you change the rules of the puzzle half way through, the time will be longer still.

And that’s the ‘holiday paradox’. The very same things that makes time feel short when you’re in it – mental engagement and context changes – will make it feel long when you remember it. In Lisbon, all that novelty and change had made the day feel much longer when I remembered it.

The most convincing theory to explain this is that retrospective duration is tallied up by checking the number of new memories formed and then guesstimating the time that’s passed. ‘Retrospective estimation of a past event’s duration is based on the naive assumption that the more data that was stored in memory during an interval, the longer that interval should be’ (4). When you’re waiting in a queue or boiling water, there’s no novelty that warrants those moments being committed to memory. They fall back into the giant gloop of queues and water boiling that you’ve experienced thousands of times before.

In Lisbon, each part of the day (Castle, tunnels, initiation well, Malkovich, Beach bar) formed an individual episodic memory. Compared to a regular Dublin day, lots of novelty and ‘scene/context changes’ had occurred, aiding each part of the day to form a little pearl of memory. When my brain needed to feel out how long the day was, it tallied up that string of pearls and overestimated the time. ‘The reason you feel as though you’ve been away for ages is that so many new things have happened that you have far more new memories than in a normal week, warping your standard measurement of time’ (5).

The opposite is true too. I remember one summer holiday from school, when I was 14, I sat around watching daytime tv and playing N64 games. Boredom stretched out each individual day (prospective), but when I remembered it all before school started it felt like only a few weeks (retrospective). The long summer had melted the days together like a chocolate bar left in your pocket, all the individual pieces days together into one molten mass of time, and my brain had very few clearly demarcated memories to tally up.

We experience these time-glitches in other ways too. The first day of something – school, work, college, date – can feel too fast at the time, and then feel long on reflection. The walk to a new place, where you’re seeing everything for the first time, can feel much longer than the walk back (6). I’d also hazard a guess that this is why the start of a relationship can rush past you at the time but feel so long in memory, as you experience so much novelty in first getting to know a person. In one of my favourite comedy scenes, from The Jerk, Steve Martin explains to his new girlfriend ‘I know we’ve only known each other for 4 weeks and 3 days, but to me it seems like 9 weeks and 5 days’.

If anything, the holiday paradox is a reminder that engaging in novelty and change, and pushing ourselves through challenges is the best way to live a life that will feel long in memory, even if it flies by us as we live it.

References:

(1) Claudia Hammond’s Time Warped, p.142.

(2) Wittman & Van Wassenhove, 2009, p1809.

(3) Zakay & Block, 2004.

(4) Zakay, The Psychologist, August, 2012, p. 578.

(5) Hammond, p143.

(6) Hammond, p19.