When Will I Get My Nobel Prize?

Some of the greatest breakthroughs in science have occurred by scientists at an early age. Take for example Albert Einstein, who at the age of 26 made several contributions to the field of science including his work on the theory of relativity and Brownian motion. Also, Isaac Newton produced his best work on calculus and theories of gravitation at the age of 23. It is well known that for endurance sports such as cycling and running, we hit a peak performance in our late 20s… So is there any relationship between age and scientific genius?

Benjamin Jones & Bruce Weinberg investigated this possible relationship in a paper published in PNAS. They used the information available on Nobel Prize winners (from 1901-2008), to explore at what age scientists carried out their most important research. They found that if you are going to get a Nobel Prize you are most likely to do the work which leads to the prize in your mid/late 30s. For those of you already past your late 30s, don’t despair! This data only takes into account Nobel Prize winners; many great scientists haven’t won Nobel Prizes and have produced excellent science to a very late age. Stephen Hawking, who hasn’t won a Nobel Prize, recently published a paper without even going through the peer review process. He is such a genius that he can just throw his ideas out there and they are taken very seriously by his peers! If I published a paper without review, nobody would even hear about it (except maybe you guys on HeadStuff.org).

Work from this study by Jones and his co-workers has been beautifully written in a recently published working manuscript for a future book (Handbook of Genius) in the National Bureau of Economic Research. Here you can freely download the book chapter which explains, in economic terms, the relationship between age and scientific creativity. Jones and colleagues have compiled data from Nobel Prize winners using many different sources and made several conclusions as to why genius tends to peak in the late 30s.

Some of the greatest breakthroughs in science have occurred by scientists at an early age. Take for example Albert Einstein, who at the age of 26 made several contributions to the field of science including his work on the theory of relativity and Brownian motion. Also, Isaac Newton produced his best work on calculus and theories of gravitation at the age of 23. It is well known that for endurance sports such as cycling and running, we hit a peak performance in our late 20s… So is there any relationship between age and scientific genius?

Benjamin Jones & Bruce Weinberg investigated this possible relationship in a paper published in PNAS. They used the information available on Nobel Prize winners (from 1901-2008), to explore at what age scientists carried out their most important research. They found that if you are going to get a Nobel Prize you are most likely to do the work which leads to the prize in your mid/late 30s. For those of you already past your late 30s, don’t despair! This data only takes into account Nobel Prize winners; many great scientists haven’t won Nobel Prizes and have produced excellent science to a very late age. Stephen Hawking, who hasn’t won a Nobel Prize, recently published a paper without even going through the peer review process. He is such a genius that he can just throw his ideas out there and they are taken very seriously by his peers! If I published a paper without review, nobody would even hear about it (except maybe you guys on HeadStuff.org).

Work from this study by Jones and his co-workers has been beautifully written in a recently published working manuscript for a future book (Handbook of Genius) in the National Bureau of Economic Research. Here you can freely download the book chapter which explains, in economic terms, the relationship between age and scientific creativity. Jones and colleagues have compiled data from Nobel Prize winners using many different sources and made several conclusions as to why genius tends to peak in the late 30s.

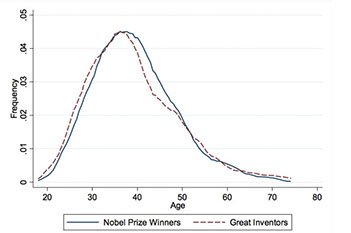

From this graph we can see that there is a sharp rise in geniuses in the early years of life, this peaks in the late 30’s before declining in a slower, albeit steep decline into old age. Source: Jones 2010.

The ideas presented in this work are quite logical, with the early years of life being dedicated to the acquirement of ‘human capital’. What does that mean? Well ‘human capital’ is an economic term for education, all great scientists need some sort of education whether that be formal education for the more modern geniuses or simply self-enlightenment as was the case for ancient geniuses such as Copernicus or Galileo (who apparently held separate jobs to financially support themselves during their most successful scientific years). The training period for more modern geniuses includes all training (university and PhD studies) up to the point where they diverge into their own independent research interests.

People are all different, the same goes for the way you go about becoming a genius. The authors break genius down into two groups; on one hand there are the geniuses like Einstein who come up with completely new, revolutionary ideas. These kinds of discoveries are made at a younger age because these scientists don’t necessarily have to learn everything that is already known in the field. Rather, these geniuses generally come up with their own ideas, which buck the trend and open the door for a boom in new discoveries. This conceptual genius is more common in fields such as Physics and Chemistry.

The other type of genius makes discoveries based on previous work, which takes a while longer because this type of genius has a ‘burden of knowledge’. There is longer time spent in the training phase, learning all of the relevant literature and joining the dots, so the scientist only becomes truly productive at a later stage of their career. This experimental genius occurs often in the fields of Biology and Medicine. Of course both types of genius can be present in all fields of science.

Scientific genius rapidly declines after your late 30s, this can be explained by changes in the interests of the field, moving on to new and exciting research questions, as well as techniques becoming obsolete. This is particularly true for the Cellular Biology field today; we have recently experienced a boom in the different techniques that have been developed, so that even modern techniques that were on the frontiers of science several years ago have now become commonplace. Of course this doesn’t take away from the importance and relevance of these techniques, it is quite the contrary, and some of these new techniques are at risk of not being integrated into the scientific community.

The authors can also explain that the decline phase of scientific genius may be directly related to health of the researchers. For an extreme example we take a look at some early Nobel laureates. Among these geniuses we can count Pierre Curie (Nobel Prize in 1903) and Marie Curie (Nobel Prize in 1903 & 1911) who exposed themselves to huge amounts of radiation during their careers as well as Wilhelm Röntgen (Nobel Prize in 1901), who discovered X-Rays. This goes to show that being on the frontier of science isn’t always good for your health!

From this graph we can see that there is a sharp rise in geniuses in the early years of life, this peaks in the late 30’s before declining in a slower, albeit steep decline into old age. Source: Jones 2010.

The ideas presented in this work are quite logical, with the early years of life being dedicated to the acquirement of ‘human capital’. What does that mean? Well ‘human capital’ is an economic term for education, all great scientists need some sort of education whether that be formal education for the more modern geniuses or simply self-enlightenment as was the case for ancient geniuses such as Copernicus or Galileo (who apparently held separate jobs to financially support themselves during their most successful scientific years). The training period for more modern geniuses includes all training (university and PhD studies) up to the point where they diverge into their own independent research interests.

People are all different, the same goes for the way you go about becoming a genius. The authors break genius down into two groups; on one hand there are the geniuses like Einstein who come up with completely new, revolutionary ideas. These kinds of discoveries are made at a younger age because these scientists don’t necessarily have to learn everything that is already known in the field. Rather, these geniuses generally come up with their own ideas, which buck the trend and open the door for a boom in new discoveries. This conceptual genius is more common in fields such as Physics and Chemistry.

The other type of genius makes discoveries based on previous work, which takes a while longer because this type of genius has a ‘burden of knowledge’. There is longer time spent in the training phase, learning all of the relevant literature and joining the dots, so the scientist only becomes truly productive at a later stage of their career. This experimental genius occurs often in the fields of Biology and Medicine. Of course both types of genius can be present in all fields of science.

Scientific genius rapidly declines after your late 30s, this can be explained by changes in the interests of the field, moving on to new and exciting research questions, as well as techniques becoming obsolete. This is particularly true for the Cellular Biology field today; we have recently experienced a boom in the different techniques that have been developed, so that even modern techniques that were on the frontiers of science several years ago have now become commonplace. Of course this doesn’t take away from the importance and relevance of these techniques, it is quite the contrary, and some of these new techniques are at risk of not being integrated into the scientific community.

The authors can also explain that the decline phase of scientific genius may be directly related to health of the researchers. For an extreme example we take a look at some early Nobel laureates. Among these geniuses we can count Pierre Curie (Nobel Prize in 1903) and Marie Curie (Nobel Prize in 1903 & 1911) who exposed themselves to huge amounts of radiation during their careers as well as Wilhelm Röntgen (Nobel Prize in 1901), who discovered X-Rays. This goes to show that being on the frontier of science isn’t always good for your health!

Nowadays, scientists who make it big early in their career often don’t get the chance to make another big discovery themselves. These geniuses can be somewhat forced into becoming glorified publicists and administrators. This is because once you make it big, you are in demand from your peers and will likely spend the next several years giving talks around the world, you will also spend a considerable amount of time writing grants to keep the cash flowing into the lab. All of these activities, which are necessary to keep science moving forward, don’t leave much time for the intensive demand of carrying out experiments. Hopefully, the people you have hired in your lab are as smart as you are and they will carry on your life’s research.

So is science really a young person’s game? I don’t think so. These geniuses that have won Nobel Prizes represent less than a handful of the geniuses working in science at the time of their discovery. Also, science is not at all an individual effort, 99.9% of discoveries are made on the back of previous experiments by other scientists. Take Einstein, he followed the work of the French mathematician Henry Poincaré very closely. While Poincaré was very close to putting his finger on the theory of relativity he couldn’t quite grasp it. However, Einstein’s brilliant young mind was able to put these phenomena into an intelligible encompassing formula “E=mc2” and Voilà, a Nobel Prize!

So who should really be credited with the Nobel Prize? Should it be awarded to one man or to the many different people who set the stage for these big discoveries? (For more info on this relativity dispute check out this great Wikipedia article). While I’m on this point, was it really just to award the Nobel Prize in physics last year to François Englert and Peter Higgs who came up with the theory of how particles acquire mass, or should they have acknowledged the 3,000+ scientists working in CERN who actually proved that this theory was true?

Although this study by Jones doesn’t really tell us anything that we didn’t already know; if you want to be successful you need to work hard, this paper raises some deeper questions;

It makes me think about how educational institutions are organised and if we could possibly do something to increase the number of geniuses in the world?

Also maybe we should evaluate how scientific funding is allocated. Young independent researchers starting out their own lab often have a hard time getting the attention of funding agencies. If we believe the data presented in this paper we should probably take more risks with young scientists because the rewards are potentially higher. However, before making any dramatic changes to the system, we must consider the possibility that if the established researchers don’t get enough money to keep their labs running, then we may find that there is not enough money to train young scientists. This would inevitably lead to a decrease in the number of geniuses. This is a complex question but I think it merits consideration.

I would really recommend taking the time to read this book chapter, it’s aimed towards scientists but it’s written in a way that avoids and explains the technical jargon of economics. I look forward to seeing the book in print so that I can find out all the secrets of how I can go about becoming a scientific genius.

Feature Image Credit