The Unbearable Whiteness of Being (Irish)

I remember realizing there was something different about me when I was only about six, sitting in the back of my parents’ car as we drove home after visiting a family-friend one day. As we were driving out of the housing estate, we passed a green area filled with kids playing. One of them, a boy a few years older than me, stopped, pointed to our car and shouted: “Look, aliens!”[pullquote]I remember being offended. Who did he think he was calling an alien? I had a regular sized head and I definitely wasn’t green[/pullquote]

The others kids laughed. My own parents laughed it off too – they were just kids after all and this was a time when there were fewer people of colour in Ireland. But I remember being offended. Who did he think he was calling me an alien? I had a regular sized head and I definitely wasn’t green – the nerve of him. Then something akin to worry and humiliation set in – he was mocking us. I became hyper-aware that there was something different about me and my family – wrong, even. After all, aliens are creepy, foreign beings. Aliens are outsiders. Aliens don’t belong here.

Up until then I didn’t know what it meant to be different; I had moved to Ireland when I was three with my family and we were settled in by then. But then this moment happened and was etched into my memory. In a way, it made me more self-aware and has always reminded me of my status as a perpetual outsider, an Other in the country I call home.

Since then, there have been various other incidents: playing outside and being chased home one day post-9/11, when I was about 10, by two boys older than me who shouted, “Is your dad a terrorist?!”; having the slur “paki” yelled out a window at me as I walked home from school on two occasions; a boy in school picking up a brown pencil and mockingly saying, “Oh look, it’s Abeeha” – I mean, I am brown but he didn’t mean it matter-of-factly, he meant it maliciously, despite his smiling while he said it. I brushed it off but I felt humiliated. Other times, the reminder that I’m different has been less overt. It takes the shape of people asking where I’m from, not being satisfied with my answer of “Dublin” and probing further: “But where are you really from? Where are you originally from?” They really want to ask: “If you’re Irish, why don’t you look it?”[pullquote] “But where are you really from? Where are you originally from?” They really want to ask: “If you’re Irish, why don’t you look it?”[/pullquote]

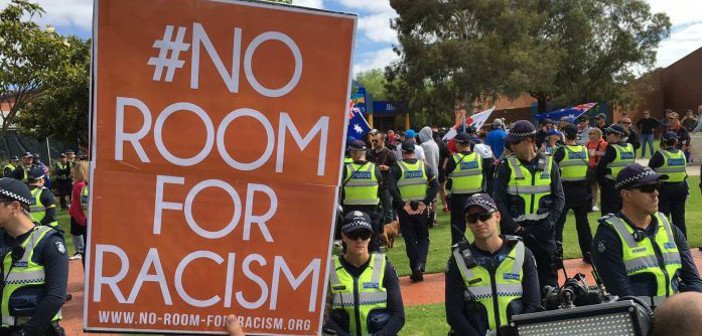

Despite Ireland’s own history of being subject to colonialism, xenophobia and immigration, racism is thriving in contemporary Ireland. Of course, we don’t really like talking about it because talking about discrimination isn’t fun. People get defensive and dismissive when racism is brought up – sure, isn’t everything fine? We’re not as bad as England or America so if you don’t like it, go on back to where you came from.

At least you’re not being killed, right? But racism and xenophobia don’t need to be physically violent to cause harm – they are underlying belief systems, hateful words, ignorant thoughts, a dismissal of one’s experiences of racism and xenophobia, and the alienation of those who do not ‘fit’ into the category of ‘Irish’. There are Irish people who actively avoid getting into taxis with black drivers; who ignorantly stereotype people of various races and ethnicities; who mock other people’s accents; who use slurs without shame; who talk degradingly about “foreign nationals” who are coming to Ireland and “taking our jobs”; who believe certain groups of people all look the same; and who tell people of colour, “You should just go back to your own country then,” lest they criticize Ireland.

Only recently, a group of black students were allegedly refused entry to a city center bar because they were black – an incident which deservedly caused outrage in the Twittersphere. Of course it’s easy to apply a discourse of damaging discrimination when it appears like this, but there seems to be willful ignorance when it comes to discussing the quiet, underhanded ways in which racism and xenophobia take form and allow more overt discrimination to occur. When the discourse on racism and xenophobia becomes more nuanced, it is more difficult to understand. So, we tend not to talk about it.

Throughout my life, I learned not to make a big deal out of the subtle discrimination that’s left a permanent mark on me. Sometimes I wonder if I’ll be looked upon less favourably for a job if they see my foreign name on my CV – will they be able to tell I speak English fluently? It’s usually well-meaning but often patronizing comments and questions about my non-Irish culture: “Are your parents going to make you have an arranged marriage?” It’s hearing about my teenage brother and his multicultural friends laughing off a grown man calling them “a bunch of foreigners,” despite them being born and raised in Ireland. It comes in the form of my parents telling me I have to work twice as hard to reap the rewards that my white peers will get for half the effort. It’s 12 year old me being afraid to wear traditional Pakistani clothes in public because of stares, comments, prejudice, and the visual emphasis of not ‘performing Irishness’ – and 21 year old me still trying to overcome that worry despite being an adult now.[pullquote]It’s 12 year old me being afraid to wear traditional Pakistani clothes in public because of stares, comments, prejudice, and the visual emphasis of not ‘performing Irishness’ – and 21 year old me still trying to overcome that worry despite being an adult now.[/pullquote]

Ireland is a small country with a rich history and an even stronger sense of identity. I’ve never felt more at home here and simultaneously more out-of-place – because Ireland’s strong identity and whiteness has often felt alienating. Stereotypically, Irish people are presented as being white-skinned, red-haired and freckled, ignoring the multitude of shades which now make up Irishness. While this representation of Irishness is stereotypical and non-representative, you would still be pressed to find Irish people of colour represented on Irish TV and radio, in Irish business, in Irish politics. Irish people of colour – our faces, our voices, our lives and experiences – are largely ignored, swept away under a cover of, “Ah sure, everything’s grand!”.

Further, a sense of Irishness is often confined to the narrow lines of hashtags such as #YouKnowYoureIrishWhen, which often constrict Irishness to being and behaving a specific way, often ruled by white Irish culture. My own sense of Irishness doesn’t neatly fit into these understandings of Irishness and when I was younger, I sometimes found myself (as mentioned earlier) trying to almost ‘perform Irishness’. But my Irishness is complex – it’s a merging of cultures and identities. Like other Irish people, my family loves their tea, but it’s called chai. It’s my grandmother giving out over the fact that I can rattle off Amhrán na bhFiann perfectly but don’t know the lyrics to Quami Taranah. My Irishness is growing up watching Winning Streak on RTÉ with my grandmother, while eating a Pakistani meal of rice and daal. It’s a childhood often spent going on family roadtrips to various counties around Ireland, trying to block out the noise of my dad playing cassettes of Pakistani folk music with my own headphones and Westlife, before requesting that a Bollywood pop song I can sing along to be played instead. My Irishness is sometimes feeling like I’m not very Irish at all.

I reckon it’s time for us to open up the borders of Irishness, and change what it means to be Irish nowadays. Beginning to openly and understandingly discuss race, culture and the evolving nature of contemporary Ireland will only help us to enrich Irishness. I’ve always known Ireland to be multicultural, complex and varied, but I still often feel as if I’m a mismatch with the ‘traditional’ sense of Irishness; I’m the loner cousin that no one really likes talking about at family get-togethers, but is put up with in the corner all the same. It’s time that we discussed the changing nature of Irishness and shed light on the non-white Irish experience, letting the alienated cousin know that they’re part of the family after all.