Why can’t every week be a four day week?

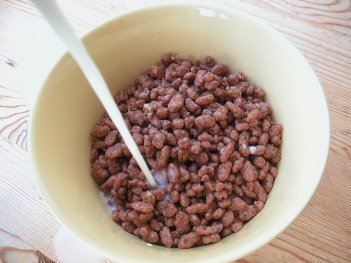

One of the sweetest things about a bank holiday is that not only do you get an extra day of taking your blanket down to the couch and watching cartoons all morning but also, when you do eventually get back to work, it will only be four days until you’re back watching He-Man with a big bowl of Coco Pops in front of you.

If you work for a company that gives Good Friday as a holiday you get to experience one of life’s great pleasures, the four day weekend sandwiched in between two four day weeks. If we could all write to our TDs and get the four day working week put on the same ballot as the marriage equality referendum, we would have the chance to create literally the best society the world has ever seen in just one visit to our respective local PE halls.

[pullquote] “The five day working week itself is a relatively recent phenomenon… It was not until 1940 that the five day week was officially adopted across the United States. [/pullquote]

Some pretty big hitters such as Mexican Telecoms’ magnate Carlos Slim, routinely first or second in lists of the world’s richest people, have gone even further with talk of reducing the working week to three days. The benefits would obviously be in creating a much healthier work life balance than is currently available, but there would also be some environmental benefits such as reducing the volume of commuter traffic. His proposal comes with some caveats though. The three days that you are in work would last eleven or twelve hours and those hours would definitely need to be spent actually working rather than playing Candy Crush. You would also be expected to work well in to your 70s and the days that we take off would not be uniform, so your weekend would not necessarily be the same as all of your friends’.

The five day working week itself is a relatively recent phenomenon. In the early part of the 20th century, some employers who had always given Sunday as a day of rest and religious adherence, also began giving Saturday too in order to accommodate Jewish workers who wanted to celebrate their Sabbath. In 1926, Henry Ford weighed in on the topic and decided to shut down his factories for both Saturday and Sunday. He went against the prevalent six day week without any reduction in pay for his workers. It was not until 1940 that the five day week was officially adopted across the United States in response to the activation of a provision in the Fair Labor Standards Act signed into law by Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1938, which mandated a forty hour week.

The five day working week itself is a relatively recent phenomenon. In the early part of the 20th century, some employers who had always given Sunday as a day of rest and religious adherence, also began giving Saturday too in order to accommodate Jewish workers who wanted to celebrate their Sabbath. In 1926, Henry Ford weighed in on the topic and decided to shut down his factories for both Saturday and Sunday. He went against the prevalent six day week without any reduction in pay for his workers. It was not until 1940 that the five day week was officially adopted across the United States in response to the activation of a provision in the Fair Labor Standards Act signed into law by Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1938, which mandated a forty hour week.

The proceeding years have seen a harmonisation across the western world towards a five day week of approximately forty hours, usually between Monday and Friday. This is not the case in many countries in the Arab world where the weekend can be Friday and Saturday, or even Thursday and Friday. Then there are some other countries that have much longer working hours, for example in Burundi the work week is a punishing fifty hours. Something to keep in mind when your boss offers you that big money move to Bujumbura. Top of this leader board, and indeed many others, is North Korea where the weekend is just one day, Sunday. Here you need to get through 54 hours of labour each week and if you don’t like it, well tough, because you can never leave.

In Ireland we are right on standard with forty hours, but with the proliferation of iPhones and BlackBerrys many employees now feel like they are never actually away from work. Physically being at the office has ceased to be the deciding factor as to whether you are working or not. The expectation that a person should be constantly in a position to respond to some demand from their work used to be reserved for the President of the US or Russia, where nuclear arms are part of the gig. Even for heads of state that was not always the case, in 1988 Charlie Haughey famously hosted French president Francois Mitterrand at his holiday home on Inishvickillane where there were no phone lines, let alone Androids or smartphones.

This constant pull on peoples’ time is difficult to square with the predictions of many futurologists in the mid-20th century who thought that advances in technology and the automation of industry would result in a great expansion of leisure time. In 1930, economist John Maynard Keynes thought the biggest problem we would have to deal with would be how to fill the endless hours of down time we would have while the robots did all the work.

[pullquote] “However, it is hard to see where the work hours will continue to come from as the internet sets about demolishing certain industries. [/pullquote]

So what happened to all that glorious down time? The key seems to be that if we were happy to accept 1930s standards we would indeed have more free time, the principle of relative needs. For instance, if we look at cleanliness standards, in the 1930s they were quite a bit lower. If someone walked into your kitchen stinking of manure that would have been considered completely fair enough (trust me on this), whereas people tend to take a dim view of that these days. The introduction of hot showers, washing machines, shampoo and so on meant that the standards of personal hygiene that had previously been the preserve of a wealthy minority proliferated and we began to wash a lot more. At that point it became pretty hard to go back to the one shower a month that would have left you with more free time.

However, it is hard to see where the work hours will continue to come from as the internet sets about demolishing certain industries. Slim’s call for the three day week would also be a strategy to counter redundancy in economies that are increasingly automated. But that assumes that we consider mass redundancy to be a bad thing and working as an absolute necessity for a fulfilling life. Architect and inventor Buckminster Fuller wanted to go way further and eliminate the idea that people should work altogether, saying:

We should do away with the absolutely specious notion that everybody has to earn a living. It is a fact today that one in ten thousand of us can make a technological breakthrough capable of supporting all the rest. The youth of today are absolutely right in recognising this nonsense of earning a living. We keep inventing jobs because of this false idea that everybody has to be employed at some kind of drudgery because, according to Malthusian Darwinian theory, he must justify his right to exist. So we have inspectors of inspectors and people making instruments for inspectors to inspect inspectors. The true business of people should be to go back to school and think about whatever it was they were thinking about before somebody came along and told them they had to earn a living.

It is possible that this is where we’re headed, but for the moment let’s start hassling our TDs and get this four day week over the line.

Image: ‘Couch Potato’ by Ronaldo Serafim

Photo: Cyclone Bill