Art Encounters | The Schnitzel Affect / How Literature Shrinks the World

Those who have dipped into this series on a regular basis will probably have picked up on a few things. Namely I’m skeptical of the merit of writing ‘reviews’. I’m not sure critical distance is real. I don’t like when the writer doesn’t actually reflect on the actual experience of writing when writing. I believe there’s something disingenuous about writing a review without informing your readers about what’s going on when doing so. This tradition of not mentioning the elephant, the thing called your life, means you appear to maintain ‘objectivity’. But subjectivity always bulges in. So I try, and probably fail, to do things a little differently. I try to explore what happens when life and art intersect, when there’s a point of combustion between what is called the subject, me writing at my desk, and what philosophers call the object: let’s say art.

Combust is a particularly apt word given that last month I travelled with my family to the Costa del Sol. While there, I (or rather we), had a combustible experience. We got sick. Yet throughout the experience, which I’ll go into soon, I read what I thought was a great novel. The World Cup had just started, and we were slouching around the beach all day, doing Spanishy stuff liking drinking cheap San Miguel tankards, and sharing plates of paella.

We had bumped into a middle-aged German woman and her three rescue dogs the evening before when out walking, and she told us she ran a German restaurant with her husband ‘Steffan’ (real name Freddy). I took this as a premonition: we would dine there the next evening. Fate was dragging the Waldrons towards what is, in all sense of the word, a simulation of a German beer garden. Not quite Disneyland, but not far off either.

When we arrived Steffan took our orders. I looked through the menu, my eye drawn toward the ‘S’ word. I couldn’t not order Schnitzel, could I? I’m in a German beer garden. It would be treason. Living and working in Germany in the 90s, I developed something of a fetish for the breaded pork synonymous with, to its detriment, Germany. And so I ordered Schnitzel and a Weisse beer. I arrived feeling bloated, and a little strange in my stomach. No better way to rejig the system – I thought – than classic German fodder and beer? Hmmm.

Two hours, three Weisse beers and a rather fantastic Schnitzel and fries later, I’m sitting on a seaside bench looking at the sea with my wife Ylva, not feeling good, on a blast of negativity that seems at odds with the calm summery vibe of the place. I’m on holidays, I should be kicking back, but I have a pain in my stomach and feel crap. I’m offloading about all that’s wrong with my life while staring at the sea. What is bloody wrong with me? I’m supposed to be on holidays, just had a lovely meal. Get a grip.

When we return to the apartment, my crappness reveals itself in all its glory. A blistering headache is followed by extreme stomach cramp that turns into a full throttle dose of the shits. I am sick. That Delhi belly kept at bay in India wreaks its revenge in Spain. I think of the paella, of Freddy who called himself Steffan. Culprits begin to appear everywhere. A foreign toilet is my new holiday destination. What would I do all day? Spanish TV seemed to have been invented to make people like me, gingers, spend the day on the beach; it had me begging for a bit of Jeremy Kyle.

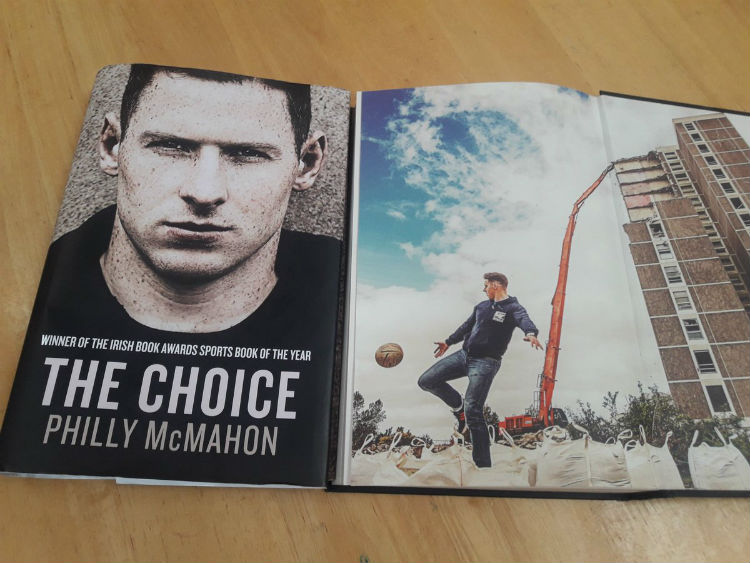

Of the three books squashed into my suitcase, I had already read one: Philly MacMahon’s The Choice. The first day in Spain I committed a classic schoolboy error thinking it wasn’t that hot due to the breeze, and it left me red all over my legs. I had launched into Philly’s book that day; captivated by his story about growing up in a vibrant Ballymun community while surrounded by poverty and drugs. Philly’s is an inspirational story about building a life against the backdrop of an older brother’s descent into full-scale heroin addiction.

Often, when I look at successful GAA players like Philly, I’m oblivious to the hardship and pain that shadows their rise to success. Reading The Choice made me look upon a player I have often screamed abuse at on All-Ireland day with a newfound sense of respect. It also got me thinking about the poverty and broken ambition in our poorest communities. Although being so engrossed left me sunburnt and dehydrated, I was taken with Philly’s story: his incessant desire to better himself faced with his brother’s situation.

So: The Choice grabbed me to such a degree I ended up sunburnt; something that I had managed to avoid ever since I was a tween in the 80s. Was it a prelude to the crappness? Was the stomach bug waiting to come out? And did the sunburn incubate it as such? Who knows? All I know is I flaked out on the couch, sleeping beneath the air conditioner unit until a day later, hours of toilet time amassed.

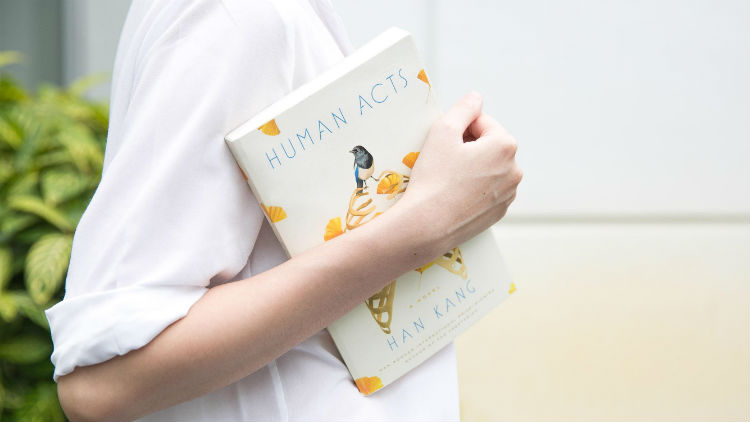

I lurched around looking for another book only to find Human Acts by the South Korean Booker Prize winning author Han Kang. It orbited my being, as if drawing me towards its dark core. I had started the novel (which is a Xmas present from my younger sister Kate) earlier that month before being sidetracked, distracted by another book arriving in the post. Human Acts is about an event – not unlike Bloody Sunday – that occurred in South Korea in 1980 that would traumatise the nation to a similar degree as Bloody Sunday in Ireland. Eimear McBride, in a Guardian review of the novel, explains the event,

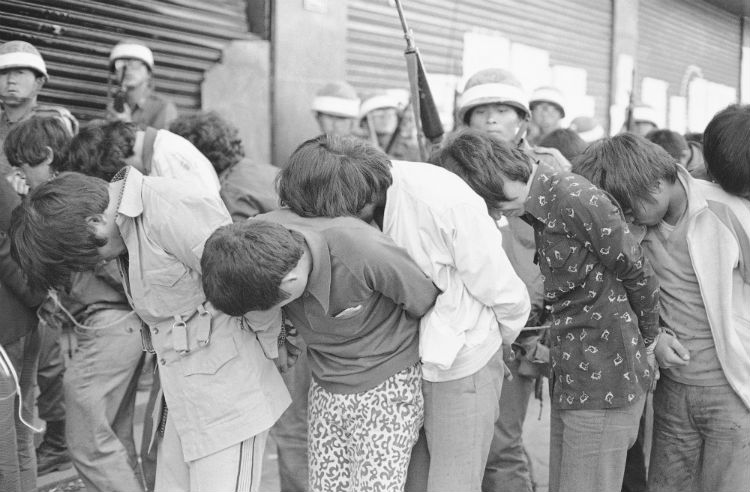

When Park, South Korea’s military dictator, was assassinated in 1979, civil unrest ensued and martial law was imposed. Recently unionised workers protested their working conditions. Greater democratisation was called for and the increasingly authoritarian government responded in the traditional fashion. On 18 May 1980, protesting students at Jeonnam University were fired upon and beaten by government troops. Outrage was widespread and citizens of all ranks took to the streets in solidarity. Special forces were sent in but, rather than calming the situation, the soldiers – spurred on to ever greater acts of brutality by their superiors – clubbed and bayonetted students, and fired live rounds into the crowds.

Now we all know horrible tragedies occur over there, wherever “there” is. Just turn on the news and you’ll be blasted with all sorts of bad stuff. You can’t think twice about a lot of horrible shit. That’s the modern condition: news and information is everywhere. It changes so often we don’t have time to process the badness of the bad stuff. It’s important that something can weasel it’s way in and change things: sway us with its poetic majesty so that we genuinely feel stuff that passes over us as information. On finishing the novel Human Acts, I sat back in awe, sick to my stomach at the thought of innocent students gunned down in daylight. I then began to wonder if my stomach illness had predisposed me to a novel about gut-wrenching sadness? Is this what I mean by combustion? Was it my sick condition that allowed me get the novel’s sadness in its fullest sense, to feel the purpose of Kang’s prose as she intended?

As McBride details the event above, one can think in response, ‘oh that’s terrible.’ But I feel the absolute destruction of the event was realised as a result of Kang’s fundamentally poetic prose; depicting the trauma and its aftermath with such delicate poise. I could feel that the destruction Kang’s novel is – in some ways – is an attempt to heal, to confront the scars inflicted on South Korean society as a result of that day.

There’s a chapter in Human Acts when we’re suddenly propelled into a victim’s afterlife: the narrative voice now that of Dong-ho, the teenager whose life and death serves as the catalyst for Kang’s awakening to a tragedy that has been central to her life without knowing it. It’s a long section from the novel that, as I lay under a sun visor on a beach on the Costa del Sol, wondering how long it would take for me to make it to a WC, had me spluttering tears into the sand. I could suddenly picture things. I could picture Dung-Ho playing with the young Han Hang as kids do. I could feel the absolute horror of his death: gunned down innocently. Suddenly gone.

How do we account for tears like this? One way is to assess our response, how it encourages us to think about stuff that relates to our own world. The great existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre used the term ‘co-efficient of generality’ to account for art’s capacity to affect and make us feel connected to the world generally. We can read a book about the death of innocent students in South Korea and we can feel a greater connection to the stuff going on here. Literature, Sartre says, can make the world shrink while maintaining the fundamental differences between its parts.

I thought of Sartre’s analysis and thought more and more about Human Acts. I thought about the massacre in South Korea in relation to Bloody Sunday. I thought of the world Han Kang reflects on as intimately related to my own (yet still different). It felt like the novel was shrinking the world in front of me, just as the crippling stomach bug was trying to dominate my senses. The novel left a gut wrenching mark on me when my body was pulling me in all sorts of directions. The world was shrinking and I felt the majestic allure of over there. Over there was suddenly also here.

I planned to give the book to my mother when I returned but when I was checking out of the apartment block I came across a whole library of books made up of those left behind by past residents unable to squash them into their Ryanair sized luggage when leaving. I took the novel out and just left it among the random collection of thrillers, bios and sports memoirs. It just seemed like the right thing to do.

Then, as the sun beat down, my youngest son went a peculiar shade of pale, said he had stomach cramps, and the process began again; inheritance is a cruel game indeed. We survived: we made it home. But the time between returning to Ireland and writing this piece got me thinking of how good Human Acts is, given that I read it lying on a beach or a bed having not eaten in three days, and somewhat afraid to eat. I read the book through a dose of the shits. That it gave so much pleasure while hanging over a toilet ‘throne’ worrying if we’d make it home, meant it was – perhaps – more than just good. Now, maybe another tourist would pick it up, head to the beach, and the world would shrink again.

To leave it there was my ‘human act’ at the end of a holiday that – from the outside – seemed somewhat disastrous. But maybe it wasn’t so bad at all? Maybe this journey to Spain, having the Schnitzel affect and getting the shits meant I was able to go on a journey to South Korea and then on to Derry, and then – more importantly – back home, this time a little older, and maybe a little bit wiser.