Art Encounters | The Rescue Act

‘The ethics of care starts from the premise that as humans we are inherently relational, responsive beings and the human condition is one of connectedness or interdependence’ – Carol Gilligan

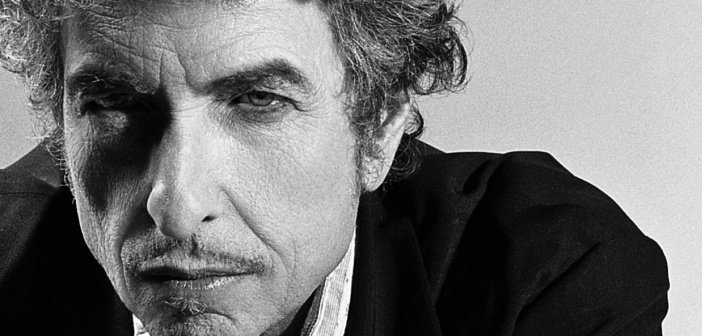

‘They say the darkest hour is just before the dawn’ – Bob Dylan

That last column I wrote in this series was about the New York hip-hop artist Nas, Bob Dylan and the Nobel Prize. I felt a little guilty after writing it, largely because I had allowed the Prize to get me hot and bothered. When you think about the Prize it’s easy forget that pitting artists against each other is just another facet of a ‘winner’ culture that probably does little to foster the spirit needed to generate real creativity. Gordon Burn, the art critic and novelist, once said that all great art comes out of packs, where the creative impulse washes over a group rather than an individual. Burn cited the YBAs (Young British Artists) as an example, and wrote about why the competitive instinct flourishes when internalised in the group, as opposed to someone imposing a group ethos from above. And that’s kind of how I felt about the Nobel Prize.

Dylan’s obvious indifference to winning the Prize confirmed a lot of people’s intuition, including my own, that Dylan doesn’t put much stock in such individual awards. Honoured no doubt, but all too aware that his significant moments have never been isolated from a community of which he is tentatively, if not integrally, a part. Bloods on the Tracks and Desire, the albums I come back to again and again, came out in the early to mid 1970s, a time when singer songwriters, and their influence on the world of music, was at it’s strongest point. Nick Drake, John Martyn, Joni Mitchel, Neil Young, Van Morrison, Carol King, are just some names. Tim Buckley, John Prine, Gram Parsons, are more. Dylan was the leader of the pack, just as Damian Hirst, as Burn says about the YBAs in the 90s, is the overbearing figure.

That I was pitting hero artists of mine against each other in some made-up competition in my head bothered me to the extent I began listening to Blood on the Tracks over and over that week. I was in its midst when I received a Whatsapp message from a friend I had told a week earlier that I was looking to adopt a dog. She said she was trying to home a Border Collie that had made its way to a derelict farm down the road from her house in East Clare. I then mulled over the idea of taking on a rescue dog over the next few days, not sure I had the capability or patience. But putting word out that I was on the look out for a Border Collie specifically (because I now live in the country and was told they’re less likely to attack sheep) meant I now faced the consequences of my actions. Truthfully, I hadn’t really thought about being offered a rescue dog that quick. Just like that. And the whole thing kind of freaked me out.

I decided to visit the dog with my son Anton, not really sure whether I was committed to taking him on, given what I’d read about the energy levels of collies and their subsequent demands. When we arrived at the farm, we walked over a large hill, across an old stone circle and into a walled garden, beside which lay a derelict 18th century farmhouse. I could see from the hill the incredible beauty of Clare shining out like I’d never seen before, as newborn lambs littered the luscious green pastures that lay all around. We then walked over gates, into an area of old sheds, where a friendly but timid animal came wagging his tail towards us. He had made an old shed his own, and the neighbours had taken it upon themselves to feed him. We played with him for twenty minutes, and felt a bond automatically. As we left he tried to follow us out a gate until we said ‘no’ repeatedly and he just lay there and whimpered. He lay on the ground as collies do, staring at us with those burning eyes, and whimpered in such a way as to pull on our heartstrings as we walked up the hill back towards the car. The sudden desire to care for this animal was overwhelming. I went home that evening with a sense of euphoria. The next week was spent preparing for this dog’s arrival.

Carol Gilligan is a feminist I have much admiration for. She developed an area of research called the ‘ethics of care’ in the 1980s. Gilligan’s writings, although controversial, have made care central to recent feminist debates. For Gilligan, our connectedness with others is fostered by the kind of care that is rooted in the feminine. Gilligan’s groundbreaking text In a Different Voice is not exclusively concerned with femininity, however, as it also explores masculinity, and in particular a sometimes-diminished sense of connection with other beings that sometimes leads to unhealthy levels of self-absorption. Gilligan has been criticized for ‘essentialising’ gender positions in her research, but her studies reveal, for me, ways of relating to the world that foster the connectedness and interdependence with other beings that is perhaps necessary and healthy. The feminine ethic of care, feminine qualities, can help counteract corrosive masculinity. It’s an area of research with implications for the Art Encounters series, because, in many ways, it explains what happened next.

I was having these thoughts at a time when I was adopting a dog, pressing me to think about the relevance of Gilligan’s ethics of care to animals. And, of course, the ethics of care includes all beings. Ethics as a practice concerns how we relate to other beings in whatever capacity, and animals are, of course, sentient beings. So as we began counting the days, which amounted to a week, when ‘Oscar,’ as he is known, would make his way to our ‘home’ from the ends of East Clare, I was taken with this idea of care. The big day was a Sunday, and that evening we drove to collect Oscar (Oscar ‘wild’ perhaps) in two cars. I drove with my son Karl, and my wife drove with my mother and son Anton. As we hit the motorway, Karl looked over at me in excitement as Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks played. I noticed I was bellowing out every line of ‘You’re a Big Girl Now,’ as if part of my very being. It wasn’t until ‘Shelter from the Storm’ came on a few songs later that a whole flurry of thoughts began to fester. Dylan sang ‘I offered up my innocence, I got repaid with scorn’ before the refrain ‘come in she said I’ll give you shelter form the storm,’ as the affect of the song began to bear its imprint on me. I was offering shelter to another being and it felt right.

Then something else happened. Words began to turn into images in my mind, and in particular one image came and lingered in my consciousness. The image in question was Bruegel’s painting Hunters in the Snow. I had been trying to figure out the meaning of this painting, with various degrees of success, for years. My interest in the painting arose from a scholarly interest in film, and in particular the Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovksy’s obsession with Bruegel’s paintings; the fact that he drew on Hunters in the Snow in a number of films as both a reference (in Solaris) and scene (in Mirror). And even though I had spoken about the paintings for years in lectures, I still never felt I fully got what was going on in Hunters in the Snow, until that moment listening to ‘Shelter from the Storm’ in the car. I pictured the painting vividly in my mind, and thought about the group of silhouetted figures returning in the dead of winter from a hunt, as the sparse glisten of snow across the valleys seems to invite them in, as an intimating and alluring feature of the natural world. I suddenly began to picture myself as one of these figures, and the group’s journey a metaphor for my own journey over the last six months. Like the figures in the picture, I felt as if I had been hunting for meaning, but meaning as difficult to find as life in the depths of a harsh winter. I had also been viewing Hunters in the Snow as a painting about death for years but when it sprang to mind like this I saw it as a painting about life; about searching for life in winter, when it seems so odds with our surroundings.

That evening as I drove over into Clare from Limerick, collected Oscar and returned to our home on the other side of the Shannon, I felt as if a metamorphosis was under way. And perhaps I had began to think of the silhouetted hunters in Hunters in the Snow, returning home with backs turned, weary bodies, and hungry dogs following from the rear, for an obvious reason: for a year now I had been hunting in the snow. It was a year since my Dad died, when one of the first concerns I had – along with my two sisters – was to find a shelter for a young puppy my father had just acquired in the weeks before his death. I remember thinking I would love to take the pup home but that it just wasn’t feasible at the time. My father lived alone in the country and the dog needed shelter straight away. When the dog was rehomed by my Dad’s friend, I was relieved: it was another thing that had to be done that was now done. But, maybe it had lingered somewhere in my thoughts that this dog was some kind of connection that was lost, and I was hunting in the meantime for something to take its place. I was a hunter in the snow, looking for some semblance of life that was temporarily gone.

But bells started ringing as I drove home that evening, reflecting on ‘Shelter from the Storm’ and Hunters in the Snow as if verse and image were somehow designed for this moment in time; as if both were meant to elicit this memory and the reflections on care I had at this time. Dylan’s lines ‘in a world of steel-eyed death, and men who are fighting to be warm, come in, she said, I’ll give ya shelter from the storm’ could well be about my Dad’s pup, my journey that evening to Clare, or the hunters in Bruegel’s painting offered, if we are imagine what happens next in the story generated by the winter scene, shelter from a ‘she’ like the ‘she’ Dylan references. The ‘she’ that is referred to throughout ‘Shelter from the Storm,’ is – of course – redemptive, a feminine protector practicing an ethic of care that fosters the interdependency of all beings: both human and nonhuman. Care involves giving shelter, giving a bit of the ‘us’ in order to gain something unquantifiable and moral.

But we should be careful not to miss an important feature: that care, shelter giving, is a two-way thing. This is what Dylan’s song and Breugel’s painting helped me grasp and Gilligan’s theory helped to grasp perhaps even further. We shouldn’t assume that offering shelter means giving way, that is, giving up something of oneself to another being without any reciprocal ethical gain for ourselves. This is what I learnt as I drove home that evening with a dog in the back of my car, shivering, huddling together with my wife Ylva, as I felt the raw power of giving shelter: caring for another life. And while I initially thought I was rescuing this dog, I would come to realise, in the days and weeks that would come to pass, we were really rescuing each other.