The Easter Rising 1916 Sean Sexton Collection | Exhibition Review

In the centenary of the Easter Rising, London’s Photographer’s Gallery is holding an exhibition of photographs highlighting critical events leading up to the rebellion, its immediate effects and also its aftermath.

Located just a few metres from London’s Oxford Street, it can be very easy to miss the Photographer’s Gallery on Ramilles Street. You can access it via a tiny staircase from the heaving shopping thoroughfare, but you’re better off wandering around Carnaby and finding it that way. Even so, the whole street feels like a bit of an afterthought, the way small London streets tend to do.

But once inside the space, nothing is an afterthought. The exhibition draws on the remarkable collection of Sean Sexton to present a small but comprehensive history of the Easter Rising. Sexton is an avid collector of rare and curious photographs, and the only ones he will not sell are from his Irish collection which now numbers more than 20,000.

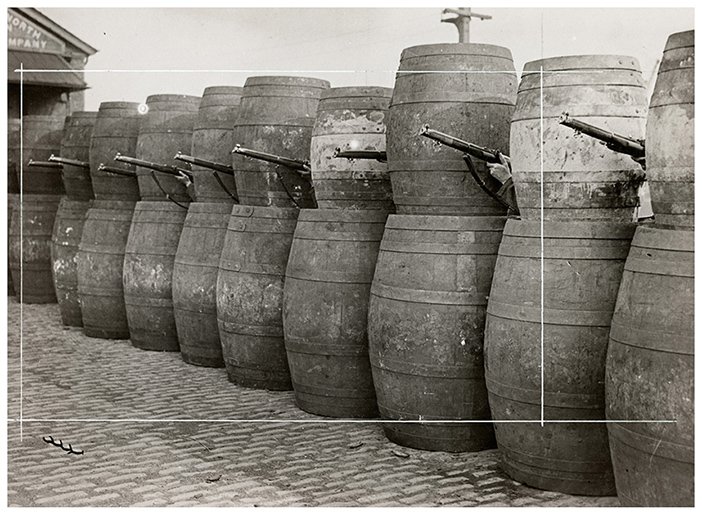

If you’re expecting nothing but pictures of destruction and war – the exact events of the rebellion – you may be sadly disappointed. The curator has done a good job of placing the Easter Rising within a larger context. The earliest photographs are from the 1860s to 1890s and show the poverty experienced in rural Ireland at that time. In one scene of tenants being evicted during the Land Wars, a young family, the children barefoot, stare directly at the camera. They are framed by the tumbledown stones of their meagre cottage. But there are also moments of defiance, such as a large outdoor mass being held in spite of the Penal Laws. Amongst these are portraits of early leaders and nationalist activists, such as John Mitchell, Charles Gavan Duffy and Michael Davitt. Progressing historically, there are then photos of damage in Dublin’s streets and some discrete scenes of violence. Apparently, few photos of the actual hostilities remain due to the difficulties of photography and ‘blanket censorship enforced by the authorities’.

I’m not Irish, and I know little about Irish history, so I enjoyed the opportunity to learn about this event in a holistic way. There were people, there were important people, there were poor farmers, there were movements and uprisings and agitation and despair – and all of these are captured in this amazing (but very small) space.

After the failure of the uprising and the execution of some of its leaders, public opinion towards Irish independence changed, and this exhibition suggests that part of this was because photos of the executed ‘martyrs’ began to widely circulate – a successful propaganda tool.

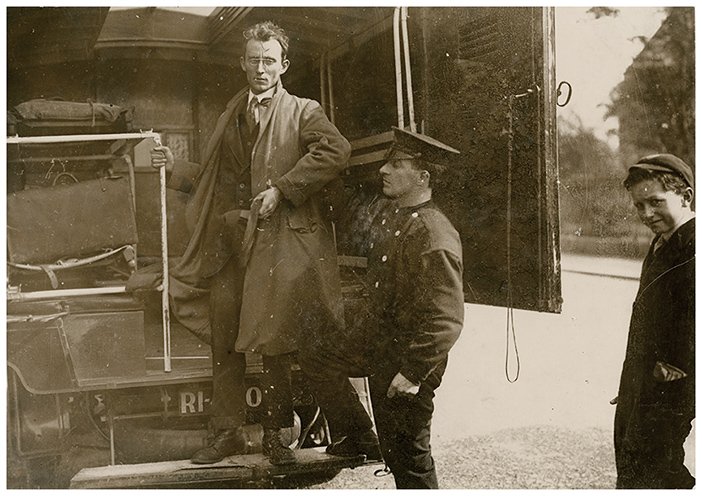

The exhibition hasn’t excluded women, either. A photo of the Countess Markievicz, revolutionary nationalist and later Irish Cabinet minister, in her full aristocratic regalia sits alongside a (posed) portrait of her with a gun. The highlight was Mrs Folkard, the Sinn Fein delegation’s cook. The delegation to London in 1921 were so suspicious of the English that they refused to eat their food, so poor Mrs Folkard joined them. She looks mostly unimpressed as she peels potatoes, framed by the plain brick exterior of the back of the house. In her plan white smock, she is a wonderful contrast.

Wandering around the exhibition and taking notes, I was surprised by the number of people coming in. And these weren’t just people glancing at the pictures and wandering off – no, these were people who were staring intently, reading carefully, chatting earnestly. This is definitely an important exhibition, at the very least for Irish people living in or visiting London, or anyone wanting to learn more about this event through contemporary and documentary sources.

Easter Rising at the Photographer’s Gallery runs until 3 April 2016.