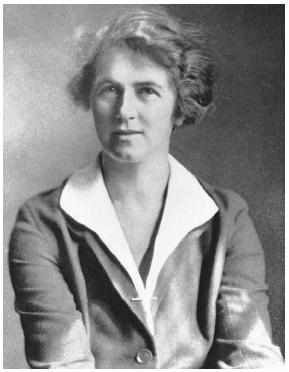

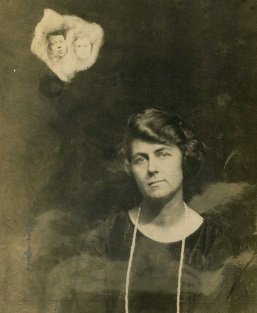

Mina Crandon, Psychic Fraudster

It seems to be hardwired into our brains to want to believe in miracles. It’s the only explanation why people will continue to believe in them even after they’ve been shown to be nothing of the sort. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the massive belief in fraudulent mediums that seized the western world in the early twentieth century. Some of the greatest scientific minds of the age would nonetheless insist that despite someone having been caught in a cheat, they still believed in their genuine psychic powers. In 1888 the former medium Margaret Fox wrote:

Spiritualism is a fraud and a deception. It is a branch of legerdemain, but it has to be closely studied to gain perfection.

Margaret went on to admit that the rapping noises in her seances were not caused by spirits, but by her cracking the joints in her feet. In response the author and spiritualist Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (creator of Sherlock Holmes) replied:

Nothing that she could say in that regard would in the least change my opinion, nor would it that of any one else who had become profoundly convinced that there is an occult influence connecting us with an invisible world.

In other words, not even the confession of a former medium could shake his faith in her powers. Even some of the mediums themselves, despite their frauds, believed that they possessed a gift that they had to share with the world. Perhaps that explains why a wealthy Boston woman would put her reputation on the line to try to become the world’s first scientifically-certified medium.

Mina originally came from Ontario, but moved to Boston when she was young. There she married a grocer named Earl Rand, but in 1918, aged thirty years old, she divorced him to marry Doctor Le Roi Goddard Crandon. She had met him while she was working as a volunteer ambulance driver in a New England naval hospital, where he was the head of surgical staff. In civilian life he was a private surgeon, which made his wife a wealthy member of the Boston social elite. At the time seances were a common practice among the ladies of high society, and Mina soon began to make a name for herself.

Houdini was at the time the most famous stage magician and escapologist in the world. Conan Doyle was convinced that Houdini himself was a psychic and that was how he actually did his tricks and escapes. Houdini’s insistence that it was just trickery, like Fox’s, failed to move Doyle. Ironically it may have been this evidence of how false such beliefs could be that motivated Houdini’s efforts in debunking fraudulent mediums. So when Bird and Carrington declared that Mina was a genuine psychic, and Bird leaked to the press that the committee was about to give Mina the prize, one headline gleefully declared “Houdini the Magician Stumped!” Houdini, who was abroad at the time and had not even had a chance to examine Mina, was livid. He cancelled the remainder of his tour, and set off for Boston.

Houdini took stock of the situation, and soon realised that his fellow committee members had hardly handled themselves as paragons of objectivity in their investigation. Most of the members had actually stayed with the Crandons during the investigation, eating their food and becoming friends with them. Some went beyond friendship – there were rumours of her having an affair with Howard Carrington, who also borrowed money from her husband. Malcolm Bird, too, was said to be infatuated with her. Mina had been described by a contemporary as “too attractive for her own good”, and generally performed her seances in a flimsy dressing gown, to prevent any allegations she had devices concealed beneath them. Houdini was having none of it.

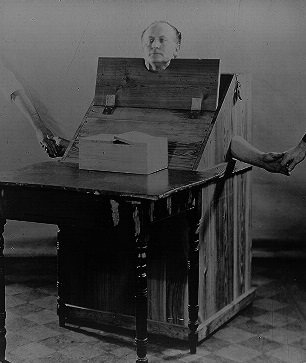

At the first sitting he attended, he was placed on her left hand, with her husband on her right. Having a deep understanding of how to manipulate his own body, Houdini knew that by wearing a tight bandage on his leg he could increase its sensitivity once the bandage was removed, and with that he was able to feel Mina’s weight shift as she reached out with her right foot (which her husband was supposed to be monitoring) to manipulate the screen that moved, and the bell that rang. The megaphone that went flying into the room was a bit more puzzling, as he had not felt the shifting that would have accompanied such a throw – until he realised that she had placed it on her head, like a dunce cap, and flung it forward using her neck. At a second seance, when he felt a table begin to move, he reached out underneath it and actually caught her hand moving it. In order to eliminate such fraud, he designed a box she could sit in with only her head and hands protruding. Reluctantly, the Crandons agreed – but then, at the next seance “Walter” proclaimed that the bell had been sabotaged, and Dr Crandon (who Houdini suspected of being the actual source of “Walter”’s voice) produced a pencil eraser that had been jammed into it. Then a collapsible ruler was found in Mina’s box, where it could have been used to cheat at the seance. The Crandons accused Houdini of planting it, while he accused them of planting and then “discovering” it in order to throw doubt on his testimony.

The committee’s debates went on for months, with Houdini furious that Bird and Carrington seemed prepared to take the word of “Walter” over his. The delay also incensed the Spiritualists, who saw it as the committee dragging its feet and refusing to admit the truth. When in the end the committee finally declared that they would not be awarding Mina the prize, there was outrage from her supporters. The announcement did nothing to stop the feud between Houdini and the Crandons, with “Walter” denouncing Houdini as a dunce. Houdini, for his part, first published a pamphlet with illustrations showing how Mina’s “miracles” could be performed, and then started to incorporate the same tricks into his act – as a comedy turn. He also offered $5000 to Mina if she could produce any effect that he could not duplicate. In response to McDougall calling him biased and unfair, he also offered $5000 “to a Harvard professor if he will consent to be thrown into the river nailed in a packing case”. Sadly on October 31, 1926, Houdini died of appendicitis, caused when an over-eager fan punched him in the stomach (as he was known to let people do) without warning him to tense the muscles first. The papers claimed that “Walter” had predicted his demise, though Mina herself spoke sympathetically of Houdini, praising his determination.

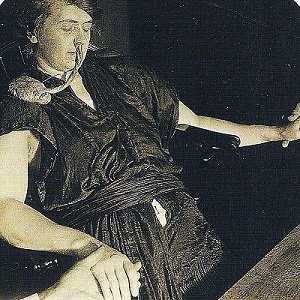

Mina’s seances continued, and continued to draw in investigators. She began to manifest ectoplasm, which looked uncommonly like lung tissue and offal, and even produced a crude hand of the stuff. Yet even believers began to have their doubts about her. Eric Dingwall, a notoriously sleazy British investigator known as “Dirty Ding” who insisted that she perform her seances in the nude, noted that in many of his photographs the ectoplasm appeared to be hanging from wires. Joseph Banks Rhine, considered the father of parapsychology, declared her a fraud. In response, Arthur Conan Doyle took out ads in American newspapers, consisting merely of the words:

J. B. RHINE IS AN ASS.

This was, in fact, a symptom of the schism that was dividing “psychical research” at the time – the division between Spiritualists (who believed that the powers of mediums came from ghosts), and parapsychologists (who believed that the power of mediums came from their own psychic energy). The Spiritualists managed to take control of the American Society for Psychical Research, and immediately began championing Mina, refusing to publish Rhine’s article calling her a fraud. In response Walter Franklin Prince (a member of the Scientific American committee) resigned and founded the Boston Society for Psychical Research, which then stood against Mina.

Further investigators also declared “Margery” a fraud, with a Harvard committee catching her producing the ectoplasmic hand from her lap, while the physicist Robert Wood (who specialised in the genuine invisible phenomena of ultra-violet light) managed to trace back one of Mina’s “ectoplasmic tendrils” with which she was manipulating objects in the dark, and discovered it to be a padded knitting needle held between her teeth. The mysterious ectoplasmic hand, on examination, turned out to be made from animal parts stitched together. Mina’s final downfall in the eyes of the public came in 1928 when “Walter” began producing thumbprints in soft wax. At first, when they proved to match neither the Crandon household not any of the sitters, there was excitement. One paper even claimed to have matched the prints to one on an older razor that the real Walter had owned. Then Mina’s dentist, Dr Frederick Caldwell, came forward. He remembered having shown the Crandons how to take fingerprints some time before, and had given them his own as a sample. Sure enough, it turned out to be an exact match for that left by “Walter”. The Boston Society eagerly published the expose, and soon the word was out that Mina had been caught in an unambiguous fraud.

Mina’s reputation never recovered. Malcolm Bird wrote a book in which he claimed to have helped fake her effects in the Scientific American seances because they had been having an affair, which Mina denied (calling him “disgusting looking”). She continued her seances, though the scientific community now ignored her. With her husband’s death of pneumonia follwoing a fall in 1939 her drinking, which had already been a problem, escalated into full-blown alcoholism. She became despondent, and on November 1 1941 she died, 25 years almost to the day after her nemesis Houdini. The biggest mystery she left behind was simply why a wealthy woman would commit such an involved set of frauds, but that was one secret that “Margery” took to her grave.

Images via wikimedia, Unbelievable, and the Library of Congress.

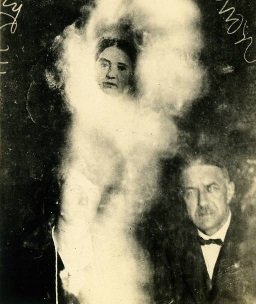

[1] The face of the grandmother in the “spirit” is actually quite a bit younger than she was when she died, presumably because this was the only photo available for the obvious fakery.

[2] The belief that a creature can pass on acquired characteristics (such as injuries, or knowledge) to its offspring. This contrasted with Darwinian evolution, which held that only inherited characteristics could be passed on.