Chester Burge, Slumlord and Murder Suspect

It speaks a lot to the integrity of a justice system when it finds somebody innocent based on the evidence, even when all involved are convinced of his guilt. The jury in Chester Burge’s trial for murder had every reason to find him guilty. He was the primary beneficiary of the murder, and perhaps more importantly he was also being charged with interracial sodomy at the time. But they decided that the case against him could not be proven, and he was exonerated. The court of public opinion, though, had a rather different verdict on the affair.

Chester Burge was born in 1904 in the city of Macon, Georgia. [1] His father Charley was a plumber; and though there were later rumours that he was not actually Chester’s father, those came long after Charley’s tragic death in a car accident. This happened in 1912 while he was walking home from work, when he was struck by a car and suffered fatal injuries. His wife Sally remarried a year later to one Ben Durden, who became Chester’s step-father. Chester himself was married in 1922 at the age of 18; a marriage that was the beginning of the first, but not the last, scandal he would cause in Macon.

Chester’s wife Laurine (maiden name Dupriest) was five years older than him, though she later claimed that she had been told he was older than he was. The marriage hit the rocks within weeks, as Laurine discovered that her new husband’s primary employment was as a petty local loan shark. She was not on board with this, and they separated less than two months after their marriage. Laurine filed for divorce, and the divorce trial was set for November of 1922. However it didn’t actually start until June the next year, for the very good reason that Chester was committed to a lunatic asylum days before the original trial date. Exactly why he was committed is unknown, except that his mother described him as “a threat to himself and others”. There is no record of him being declared insane, nor is there any record of him being declared sane; he seems to have been held entirely on his mother’s word (along with testimony from Laurine and two of his aunts). His release was similarly lacking in legal niceties, perhaps a testament to the general “laissez faire” attitude of the Maconite authorities.

If Chester’s committal to a lunatic asylum was scandalous, his divorce trial was about to elevate his infamy to new heights. Laurine had filed for divorce on grounds of “cruelty”, and so she took the stand and was asked what form that cruelty took. The answer, it turned out, was rape. Chester had forced his wife to have sex with him “four or five times a day”, despite her unwillingness – she “told him to let me alone and he said he didn’t care”. There is some evidence that Laurine suffered from curvature of the spine, which may have been why she described it as “painful to perform these repeated duties so often”. But Chester was indifferent to her pain. Marital rape was not legally recognized at that time as a crime, despite the fact that this is clearly what Chester was doing, but the jury still acknowledged the cruelty of his conduct. Laurine was granted her divorce, took back her maiden name, and never remarried.

Chester didn’t remain single for long though. In 1924 he married Mary Kennington, the daughter of a farmer who lived in the countryside near Macon. Whether she knew about his history is uncertain, though her family certainly did not. This marriage went much more smoothly than Chester’s previous one, and the pair opened a poultry farm on some of her family’s land. Their farm bordered a road, and so Chester also opened a service station which proved mildly profitable. They had a son in 1926, who Chester named after himself, and then another in 1927 who Chester named after his great-grandfather John – for reasons that will later become apparent. mystery

However it was not all smooth sailing for the Burges. Chester junior died in 1928 aged only two years old, as so many children did in those days. Then Chester senior ran into trouble with the law. His service station sold petrol legally and bootleg whiskey illegally, these being the prohibition years. Chester fell foul of the risks of the bootlegging trade when he sold some whiskey to an undercover policeman and wound up serving a year in prison.

The end of prohibition meant an end to bootlegging, so Chester was forced to branch out in order to maintain his income. He decided to go into real estate, though he did have a slight problem in that he wasn’t legally allowed to own any real estate. Since he had never officially been declared competent after his release from the asylum, he was still officially mentally incompetent in the eyes of the law. So all the property was actually in Mary’s name, though she had no hand in any of the management of it. Or rather the mis-management of it; Chester was an unashamed slumlord who had no shame in exploiting his tenants and in skimping on any repairs to their dwellings. He would sell them their houses if they wished, but this was through a semi-legal arrangement where he was both the vendor and the mortgager on the property. The mortgage contract ensured that any missed payments caused the property to revert to Chester regardless of how much the buyer had paid; something that they were initially unaware of as Chester made a habit of selling to the illiterate. This practice so disturbed Chester’s attorney that he started surreptitiously warning the buyers of the risks they were running.

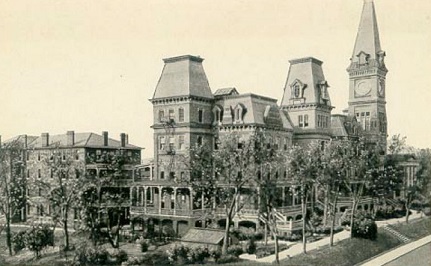

Renting out slums and predatory lending made Chester a lot of money, but it didn’t get him much respect. Opening a nightclub (called The Eldorado) gave him somewhat more social capital, at least among the less uptight members of society. That wasn’t enough for him, though. The premier family of Macon were the Dunlaps, back from when Captain Samuel Scott Dunlap had successfully defended the city for the Confederacy during a Civil War battle. Chester was distantly related to the Dunlaps; Captain Samuel Dunlap had married a daughter of the great-grandfather Chester had named his son John after. Now as the fortunes of the Dunlap clan waned, Chester moved in. Through the 1920s and the 1930s members of the family died off and their numbers dwindled. By 1939 there were only three sisters left, daughters of Captain Samuel Dunlap. Then they became one less when Ilah Dunlap Little died while holidaying in Germany in July of 1939.

It might seem odd that someone would take a holiday in Germany in the summer of 1939, if one was unfamiliar with the deep self-absorption of the upper class American. Foreign affairs were for foreigners to worry about, and to interrupt her long-established routine simply because of some political scuffles was not even to be considered. What complicated things was that Ilah had been traveling with her jewelry, worth $200,000 in 1939 dollars, and the American consul in Dresden refused to trust it to a courier. They would only entrust it to a relative, and Ilah’s only two close relatives were her sisters Nettie and Clara. Nettie was on her deathbed, and Clara was too old and fragile to travel. It was the chance Chester had been waiting for.

Clara was already somewhat well-disposed towards Chester as he had made a habit of sending her flowers – violets, her favourite. When this crisis arose he approached her to offer his services, and they were accepted. Somehow Chester made it to Dresden and back before the 1st September, when those political scuffles turned into outright continental war. The jewels were sent on to New York via American Express, where they were received by the Dunlap family lawyer. He was in for a shock, though. It turned out that Ilah didn’t actually have the habit of traveling abroad with a fortune in jewels; instead her jewelry were “paste” – worthless replicas. One necklace, which had been valued by the Germans as worth $60,000 dollars, turned out to be worth $61.50. Chester’s mission across the Atlantic had been entirely unnecessary, but it had proved him to the Dunlap family. Now he was finally In.

Nettie died less than two months after Ilah, leaving Clara Dunlap Badgley as the last of “the” Dunlaps. Over the next few years Chester continued to burrow into her good graces, and did his best to alienate her from everyone else in her life. In 1944, while taking her to see doctors in Baltimore, he persuaded her to write a new will leaving her estate (worth about half a million dollars) to his son John. (Chester still hadn’t had himself declared competent, in case he had to avoided being drafted.) Another will in 1945 left part of the estate to Mary, and the rest to her in trust for John until he turned 35. This will was signed on January 11th, and on January 14th Clara Dunlap Badgley died.

Foul play was rumoured, though she was old enough and ill enough that her death wasn’t entirely unexpected. The worst that people could say was that her doctors had forbidden her alcohol but that she had drunk several martinis the afternoon she died. Still, who would begrudge her that? The will was contested, of course. Her 1939 will (written after Nettie’s death) had left her estate to various charities, and they challenged that the two wills written after that were the result of coercion and fraud. The court case was hotly contested, but eventually it was concluded by an out of court settlement. John Burge received the plantation and about 20% of the estate. Mary was given “clear title” to the gifts that Clara had given her over the last five years. The reminder was divided out in the proportions set out by the 1939 will, which was accepted as the “most valid” of the wills.

In the years following the war John Burge did his best to break away from his father’s shadow. Though he was on paper the owner of the plantation and estate house, he allowed his father and mother free use of it while he attended college. In 1949 he was married to Caroline Cook, a fellow student from a distinguished family. Like his father though, his first marriage was a short-lived one. John had hoped to move into a bungalow with her, but Chester overruled him. They moved in to the Burges estate, and Caroline soon found out that she wasn’t allowed to leave. Chester and Mary expected her to abandon her former life and become an addendum of theirs, something the popular and ambitious Caroline wasn’t willing to do. She was forced to mount an escape involving her mother, a prearranged rendezvous with a car, and a sprint out of the house with only what she could carry. Clearly she was afraid that any discovery of her arrangements would end extremely badly. Eleven months after she left, John filed for divorce. The grounds were cruelty on her part; absurd on the face of it, but in exchange for payment of her legal fees Caroline did not contest it. Like Chester’s first wife Laurine, she immediately resumed her maiden name.

Rather than leave John to mope, Chester decided to arrange a new marriage for him. He fixed on the grandaughter of some friends of his, a woman named Anne Gerin. Anne came up to Macon to visit her grandparents and the pair were introduced. Anne disliked Chester and did not intend to marry John, but she was polite enough to them that they decided the deal was sealed. When her mother found out that John was divorced, she was also set against the marriage. The Burges convinced her grandmother Anna Oleson that she was willing though, and so Anna found herself roped into what she didn’t realise was a plot to kidnap Anne and force her to marry John. Once she realised what was happening she helped Anne to escape. In an ironic twist, another of John’s relationships ended with a woman running from a house to her mother in a waiting getaway car.

In 1952, John remarried to Jo-Lynn Scott, and like his father he seemed to find his second wife a lot more amenable. He had two children, a son and a daughter. The son, named John Lee, had a medical condition that required expensive treatments. Chester agreed to pay for these, but only if the boy came to live with him and Mary. As a result John Lee was actually raised by his grandparents. Chester’s mother Sarah moved in with them too, and the household was rounded out by a cook, a handyman, and a chauffeur. Chester was deeply racist, yet despite this (or perhaps because of it) he only hired black servants, all usually people on parole from prison. In 1957 he hired a man named Louis Roosevelt Johnson as his chauffeur. Louis was intelligent, educated, and a murderer. He was on parole for killing a woman in 1948.

Over the years Chester became more notorious in Macon, and not just for his temper and combative attitude. Sexual shenanigans were a common occurrence in the dissipated fringe just below the upper classes that Chester inhabited, including the classic “car key parties” of swinger legend. That wouldn’t have been too bad, but Chester was bisexual. [1] His exploits with the younger sons of Georgian aristocracy led to his lawyer being ordered by another client to drop him, among other incidents. In one case he arranged with the family of a local teenager to have the boy accompany him on a trip to Europe. Mary Burge tolerated her husband (and her son) drinking and sleeping around, but child abuse was a line she wasn’t prepared to cross. So she visited the family and told them the real reason why Chester was being so generous. The boy’s mother (who had no idea) forced the trip to be canceled. In over thirty years of marriage it was the first time that Mary had thwarted one of her husband’s whims so publicly. And Chester was not a man who took thwarting well.

In April of 1960 a new scandal struck the Burges when they were targeted by the KKK. Chester primarily rented to black families, despite his racism, since it was easier to take advantage of him. As a result he had rented a house in a white neighbourhood to a black family, an accidentally integrationist act that the Klan took issue with. They came to his house to “light a cross on his lawn”, though rather than the traditional burning cross this one was actually electric. Things took a turn for the farcical when they were unable to find anywhere to plug it in. Chester was naturally less than diplomatic (threatening the protesters with a pistol) but Mary brokered a diplomatic solution. If a white family applied to rent the property, the unfortunate black family would be immediately evicted in their favour. Until then the property would stay as it was, so that the Burges would not have to suffer financially.

A couple of weeks after the KKK incident, Chester checked into a hospital in Macon – the same one where his father had died. He was in for a hernia operation, but while there he decided to have some elective surgery to remove some moles on his back and legs. While he was recovering from the hernia operation there was a disturbing incident back at his estate. Mary’s pet parrot, a notoriously loud and ill-tempered creature, died due to internal bleeding (source unknown). Something more disturbing in retrospect was that Mary paid off her tab at the local grocery store, something she normally only did at the end of the month. Rex Elder, the grocer, would later comment that it made him think that she knew what was going to happen to her. If she did, it didn’t help her. On the morning of May 12th Jessie Mae Holland, the cook and maid, sent John Lee off to school and then went upstairs to see why her mistress was so late in rising. She found Mary Burge quite dead, murdered during the night.

The police quickly converged on the house, as did the media. Chester first heard of his wife’s death on the twelve o’clock news. He wanted to go home immediately, and the doctors agreed to let him go home briefly in an ambulance. He was able to tell the police that two diamond clips and about $5000 in cash were missing from the house. A diamond ring was left on Mary’s hand, but the killer had nearly removed her finger trying to get it. Though the police were quick to label the attack as a robbery gone wrong, there were some odd inconsistencies. A diamond necklace worth $25,000 that Mary had been photographed wearing many times was left sitting in a drawer in the bedroom. And the cause of death (strangled from behind while standing) did not fit the “robbery gone wrong” scenario. The case, it seemed, might not be so simple.

Jessie Mae and Louis the chauffeur were arrested almost immediately, along with Chester’s former chauffeur and three of his tenants who had been heard to complain about him. All of those arrested were black so the Georgian police didn’t bother with formal charges or with providing lawyers, of course. In contrast the Ku Klux Klan members who had been at Chester’s house a few weeks earlier were given the benefit of the doubt when they said they had nothing to do with the murder. The newspapers soon began to speculate that robbery wasn’t actually the motive for the murder, and several picked up on the death of the parrot a few days earlier. The family dog had also been locked in the basement that night; something which was not unprecedented but which did seem a bit of a coincidence. A week after the murder Chester offered a $5000 reward for the murderer of his wife. Later that day he himself was arrested.

The police were forced to jump the gun on arresting Chester, as they’d found out that he planned to take a holiday in Europe in June. As it was they held him “under psychiatric observation” without charge for ten days before they officially accused him of Mary’s murder. They claimed that the could prove he was in the house on the night of the murder (despite being in recovery from surgery). As his defense Chester retained the same team of attorneys who had successfully prosecuted the infamous local poisoner Anjette Lyles two years earlier. They pushed to have him released on the grounds that there were insufficient grounds to charge him. This forced the police to present their evidence to a grand jury in order to have Chester indicted for trial. This happened on the 6th June, but the real shocker (and what kicked the media feeding frenzy into high gear) was the second charge presented against Chester. He was charged with “unlawful carnal knowledge” of his black chauffeur, Louis Roosevelt.

Chester’s attorneys were only prepared to defend him on the murder charge, but they condemned the sodomy charge as a blatant attempt to prejudice Chester’s murder trial. They were able to force a coroner’s inquest on August 16th before the trial for the murder charge, allowing them to see the police evidence in advance.. That evidence placing Chester at the scene was a “fresh” fingerprint, found on a door that had been washed the day before. It wasn’t enough for the coroner’s jury to put the murder on him, and they returned a verdict of murder by persons unknown. Chester’s attorneys tried to use that to get him released on bail, but they were unsuccessful. Around the same time Chester received another blow when he found out that Mary’s will had prompted an IRS investigation, and her estate (which is to say, his company) owed over $342,000 in back taxes.

Chester paid $50,000 for his defence team, and they turned out to be worth every penny. In their opening argument they admitted that Chester was far from a perfect person (a nod to the upcoming sodomy trial) but they insisted he was not a murderer. Instead they claimed that he had been arrested by a police department under pressure to find a suspect, despite a lack of any clear evidence. They also admitted to Chester and Mary having a strained marriage, and said that they believed the state would (in the lack of any evidence) seek to put Chester’s character on trial. In short, they undercut the prosecution completely. Another key factor from the defense was that Mary had fought back and scratched the attacker, but the nurses at the hospital who bathed Chester could testify to his lack of any such wounds.

The prosecution had no difficulty in establishing motive and inclination. Chester’s own mother testified to having seen him beat Mary over a trivial argument, and other witnesses demonstrated his fury whenever she blocked any of his business plans. The robbery motive was thoroughly dismantled. But as the defense had suggested, hard evidence was thin on the ground. The jury debated the case for some time, but though some of them did think that Chester was guilty they all had to agree that the prosecution had not proved their case. As a result Chester was acquitted of Mary’s murder, though he was not (in the public mind) absolved.

Nobody was ever convicted of killing Mary Burge, and the people of Macon were generally convinced that Chester had done it and got away with it. In retrospect it was the insistence of the police that he had been present at the scene which scuppered their case; if they had tried to show that he had paid for someone else to kill Mary (the most common supposition) then they might have had more luck. But that would have required them to find the actual killers, and they were under a lot of pressure to produce results. If Chester had been convicted of the murder then he would have faced the death penalty, but the police weren’t too sad about losing the case. They knew that his life as he’d known it was over; and one investigating officer told his wife: “He’s dead, anyway”.

After the murder trial Chester was released on bail pending his sodomy trial, but he did not return to the mansion where Mary had died. John took this opportunity to seize the ascendancy over his father, and since he had been left the house by Mary then he took over possession of it. He took over something else as well: his son. Chester never saw his grandson, John Lee, ever again. Instead Chester left town to stay with a friend, until he had to return two weeks later to go to court once more. During that time he tried to find attorneys to represent him, and once he did they tried to have his case delayed until January. But they failed. On the 8th December 1960 Chester’s trial began.

The prosecution case was simple. Chester had begun having sex with Louis shortly after he had hired him in 1957, and these acts had continued throughout his employment. According to their evidence Chester had deliberately hired a man on parole from jail so that he could threaten him with having it revoked if he didn’t go along. Louis was their star witness, clearly cooperating in the hope of avoiding prosecution himself. Other witnesses included Chester’s previous chauffeur (who claimed that Chester had propositioned him but had been turned down) and a relative of Chester’s named Edwin Kyle. Kyle was the cause of John and Jo-Lynn Burge being charged with contempt, after it emerged they had tried to pressure him not to testify.

There were no witnesses for the defence (other than an unsworn statement from Chester himself), but they ferociously cross-examined all the prosecution witnesses. One point they did raise was that none of these accusations predated the murder trial. Another, less salient, point came out at the start of the defense’s summing up; when attorney W Cooper pointed out (with the aid of the usual racial slur) that almost all of the prosecution witnesses were black. This wasn’t enough to convince the jury though, and they found Chester guilty.

During his unsworn statement Chester had admitted that he was suffering from tuberculosis, and that this was the reason for his ill-health. Based on medical confirmation he was freed on bail pending appeal. While the appeals process was working its way through the courts he returned to his hideout in Camden, South Carolina. There he met up with an old friend named Anna Dickie Oleson, a former politician and the widow of a lifelong friend of Chesters. This was the same Anna Oleson who was the grandmother of Anne Gerin, the woman who had been kidnapped and almost forced to marry John Burge ten years earlier. She had remained friends with Chester, and the two apparently hit it off. Like him she was widowed, though at 75 she was eighteen years older than Chester. As such it raised a few eyebrows when the pair were married in April of 1961.

A month after he was married, Chester’s appeal against his conviction for sodomy was successful. His grounds had been that Louise Roosevelt was an “accomplice” in the act, and so could not act as a witness to prove that it had taken place. This was what the prosecution had tried to avoid by establishing that he had been acting under duress, but the appeals court decided this had not been proven (mostly due to Louis not having said anything before his arrest after the murder). The state chose not to retry Chester, and so he was a free man.

Chester and Anna celebrated with a honeymoon cruise, after which he and Anna decided to move to Palm Beach in Florida. However the shine soon went off the marriage. Anna’s daughter Mary (Anne Gerin’s mother, who had rescued her from the Burge house) had been opposed to the marriage from the start, and was convinced that her mother was going to be Chester’s next victim. In August of 1963 Anna Burge made a trip to Macon, visiting John and Jo-Lynn Burge as well as a psychiatrist who had examined him during the trial and several of the police officers involved in the investigation. They all advised her not to go back to Florida, and she didn’t. She would never see Chester alive again.

On the 7th October 1963 Chester Burge’s house in Palm beach exploded. Chester survived the initial blast and ran out into the street in front of the house. He died of his burns in hospital. There was nobody else in the house at the time. It was reported in the Florida papers as a gas explosion, though the Macon papers were convinced it was either suicide or murder. The official verdict was accidental, though the reports are full of inconsistencies. On the other hand, there was no real evidence for anything else beyond the people of Macon being convinced of Chester’s duplicity.

Chester’s original will had been invalidated when he married and he had never made another, so he died intestate. This looked like it might trigger a series of lawsuits between Anna and John Burge, but Anna made the decision to give up her interest in his Georgia estate in exchange for the repayment of $40,000 she had loaned him in order to buy the house in Palm Beach. She moved back to Minnesota where she died eight years later, and was buried next to her first husband. Chester was buried in Macon, though there is no marker on his grave. It may be that the town did its best to forget that he had ever existed.

Images via wikimedia and A Peculiar Tribe of People except where stated.

[1] A concept that seems to have been alien to the thought processes of people at the time. One person interviewed for Richard Hutto’s excellent biography of Chester said, when asked about him participating in the key parties: “I guess Chester did that so everyone would think he was straight.”