Gracia Mendes Nasi, Renaissance Businesswoman

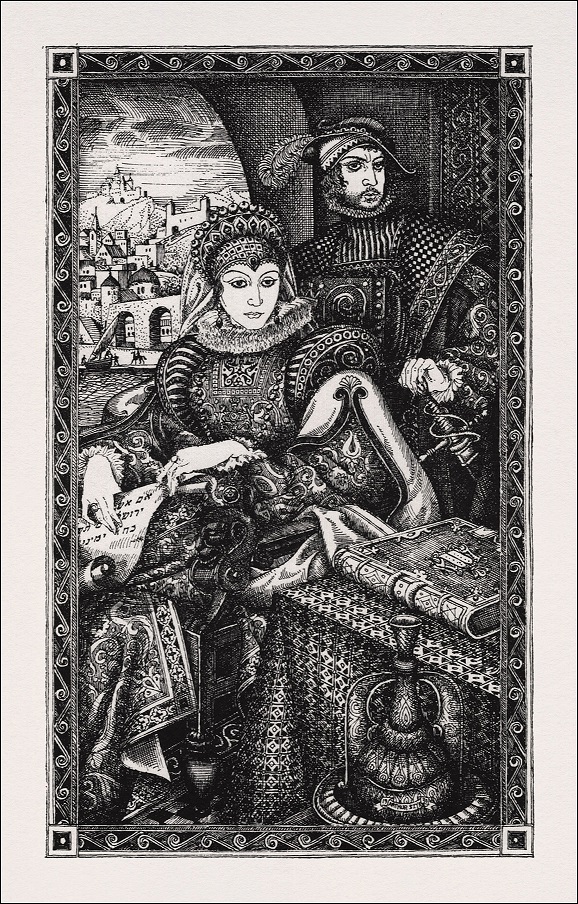

Throughout medieval times, the Jews of Europe had a hard time as the traditional scapegoats for any misfortune that befell communities. Rather than admit that they themselves might be at fault (or indeed that things might just happen) it was easier for people to decide that plague, famine or floods were divine punishment on them for tolerating these “infidels” in their midst. Far from being discouraged, this was actively encouraged both by a church seeking to establish itself as the sole arbiter of truth and by rulers who desired to take the riches of these “infidels” for themselves. When Gracia Mendes Nasi, a young Jewish widow, became the head of one of the richest families in Europe then it seemed like a foregone conclusion to those rulers that one or the other of them would claim that fortune “for Christendom”. But they hadn’t reckoned with Gracia having different ideas.

Gracia was born in Portugal in 1510 as Beatriz de Luna, or at least that’s what the world thought. The real name her parents gave her was Hannah, but her parents lived a secret double life. They were “Conversos” – Jews who had been forcibly converted to Christianity by royal decree, or who had publicly converted in order to try to avoid the deadly prejudice of their neighbours. The plague in Lisbon in 1506, for example, had been blamed by religious fanatics on “Jews poisoning wells” and so a mob led by Dominican friars murdered nearly two thousand Jews over the course of a few days. In that case, Conversos were not exempt from the slaughter. Many suspected that their conversion was only a public affair, and that they still secretly practiced their Judaism. And in many cases, including that of the Luna/Nasi family, they were right.

It was a dangerous thing to be a “crypto-Jew” of that sort. The majority of the Conversos abandoned their old religion, but they were still the primary target of the Spanish Inquisition which tortured many of them, and burned at the stake any they found still practicing Hebrew traditions. Those secret Jews they found only fueled their paranoia and hateful faith, leading to even more persecution. When Gracia [1] was born the Inquisition hadn’t yet come to Portugal, but her family would still have been murdered by the state if their secret Judaism had been found out. So she grew up with two names, and held the real one inside her heart.

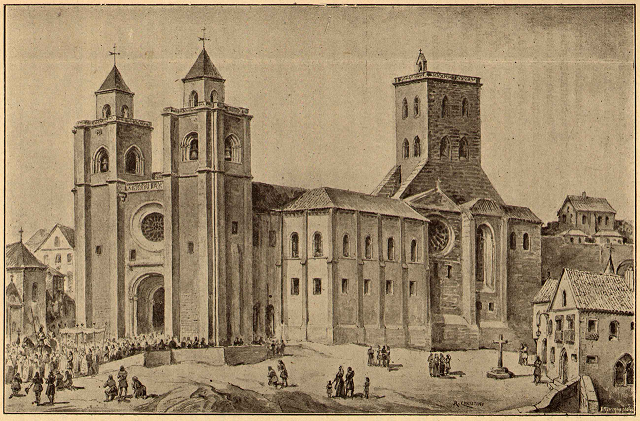

Gracia had “married well”. The Luna family were one of the richest families in Lisbon, but the Mendes family were one of the richest in Europe. Originally a banking family, they had helped finance the expeditions that had gone round the Cape of Good Hope and found a sea route to India. This put them in control of the emerging spice trade, a role that earned them the title of “the kings of black pepper”. It was to grow this trade that Francisco sent his brother Diogo to Antwerp in the 1530s in order to set up a business centre there. Officially part of the Spanish Empire but exempt from the rigors of the Inquisition, Antwerp (in the heart of modern Belgium) had taken advantage of its “free city” status to become the trading capital of Europe. It was the logical place for the House of Mendes to plant their flag.

There were other reasons for the establishment of an outpost in Antwerp, though. In 1536 the Pope had ordered the King of Portugal to establish an Inquisition, and it was clear that Lisbon was becoming less safe. Francisco and Gracia had recently had their first child, a daughter named Reyna (with the public name of “Ana”), and they were clearly preparing to move their family to a more secure location. When Francisco died in 1538 Gracia did not let this derail their plans. She got on a boat along with her younger sister Brianda de Luna and baby Reyna. (The baby was actually named after Brianda, “Reina” was her true name.) They went first to England (which was under Cromwell’s rule at the time), and from there on to Antwerp.

Fernando’s will left control of the company divided between Gracia and his brother Diogo. Diogo was just as financially gifted as Fernando was, and in fact when there were rumours of him being arrested as a heretic in Antwerp the city’s financial leaders banded together and told the authorities that arresting Diogo would utterly destroy the city’s economy. Part of the acumen was the ability to recognise and respect talent, and he was well aware that Gracia had been running the Lisbon end of the operation for quite some time during his brother’s illness. So he gave her that share of control without griping, and to seal the deal their families were once again reunited in marriage. Some Hebrew traditions would have obligated Diogo to marry his brother’s widow, but Catholic traditions at the time would have regarded that as incest unless Gracia’s previous marriage was annulled. So instead Diogo married Brianda, who soon gave birth to a daughter. Like Gracia’s daughter, she was named after her aunt – Beatriz to the world, and Hannah to her family.

Sadly, this amity between the sisters wasn’t going to last. Diogo died in 1542, and his will not only confirmed that Gracia owned half of the family fortune but also left her as the executor of the other half of the estate on behalf of Diogo’s widow and daughter. The official guardian of the infant Beatriz was also Gracia and not Brianda. Clearly Diogo regarded Gracia as a suitable person to lead the House of Mendes. However it was a serious snub to Brianda and led to a rift between the sisters at a seriously inconvenient time. Because the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, was about to try to take away everything they had.

In 1540, while Diogo was still alive, the Emperor had ordered the magistrates of Antwerp to begin investigating “suspected Jews”. This was not an Inquisition; this was a shakedown. Charles hoped to reap a rich harvest of bribes from the merchants in order to exempt them from the investigation. (This was also around the time he was persecuting Lutherans, so there were plenty of examples to show how badly such investigations could go for you.) As a result, many merchants decided to move to Venice. The family may have been planning this before Diogo’s death disrupted things. And with a woman now heading up the family, unscrupulous men soon began to move in. An elderly Spaniard named Don Fernando de Aragon, for example, made a plan to marry the infant Reina and so seize control as the sole male member of the family. He recruited the Emperor to press his suit with the promise of a substantial percentage of the Mendes fortune.

Charles and his sister Mary (governess of the Netherlands, and so in charge of Antwerp at the time) invited Gracia to visit them; a common tactic used by the royal families of Europe to then effectively imprison and then coerce people. Naturally part of the tactic was that it was considered “impolite” to refuse such an invitation, but Gracia was wise to them and faked an illness. They continued to press Don Fernando’s suit, but that wasn’t their only plan. Gracia soon found out that they were also planning to posthumously convict Diogo of heresy and use this as a pretext to seize the Mendes fortune. Convinced they were in imminent peril the women took all the valuables they could and went on “holiday” to the town of Aachen. From there they surreptitiously fled to Venice. It was six months before the people of Antwerp realised that the Mendes sisters had ghosted them.

Left behind to manage their business and face the emperor’s wrath was their most capable lieutenant, João Miques. Like them, “João” was a secret Jew with the real name of Joseph. He may have been related to the Mendes family. If he wasn’t then his father was a good family friend of theirs, and when he died shortly after Joseph was born then the Mendes family supported him growing up. Joseph was only twenty years old at this time, and had graduated from the University of Louvain a couple of years earlier. While he was studying he had become friends with a younger student named Maximilian, who just so happened to be the son and heir of Emperor Charles V. That might be why Joseph was permitted to leave Antwerp with orders for the two woman to return and face trial as heretics. Of course they wanted to confiscate the Mendes fortune, but they couldn’t do so without charging the two women. Gracia’s defense (passed through Joseph) was that they were Portuguese subjects and so not subject to these charges. He offered an extremely large interest-free loan to Charles as a bribe. Facing pressure from the merchants of Antwerp, Charles agreed to drop the charges.

Gracia and Brianda reached Venice in 1546, where they had already established a trading business. Despite their safe conduct to the city, things were still tense. “New Christians” such as they were still socially segregated and faced a constant suspicion of still heretically practicing Judaism. Venice had an inquisition, and a cardinal not averse to denouncing members of the “New Christian” community by name. The Mendes family needed to stick together in this hostile environment. Which is why it wasn’t really a good thing that Brianda decided to sue her sister.

Brianda had never gotten over her sister being assigned guardianship of Beatriz, and officially that’s what her lawsuit was about. The real reason may have been because of Gracia’s most secret plan: to move the family to the Ottoman Empire where they could openly practice their Jewish faith and live without fear. Brianda had a comfortable life in Venice and hoped to keep it. She overplayed her hand when she revealed Gracia’s secret plan to the authorities though. Rather than withdraw Gracia’s passport (as they normally would have), the Venetian authorities arrested her. They also forcibly took both Reina and Beatriz and placed them in a convent. Once again, the state was conspiring to steal the Mendes family fortune; and the foolish Brianda had given them a pretext to do it. She tried to move her own money out of Venice, but her agent turned against her and she too was denounced and her assets seized. It was a dark time for the family.

The case went to trial in 1547, but dragged on until 1548. Gracia, unsurprisingly, lost the case. Equally unsurprisingly the court did not give control over Beatriz’ half of the family fortune to Brianda but instead ordered that it be paid into the Venetian treasury to be “held in trust” until she turned eighteen. By the time the verdict was announced Gracia had been released from arrest, retrieved her daughter and secretly moved to Ferrera which was much more openly hospitable to Jews. Hospitable enough, in fact, that she was able to abandon her false name of Beatrice and for the first time publicly declare herself “Donna Gracia Nasi”; or in other words “Lady Hannah the Prince”.

Following the trial Gracia (who was still relying on her Portuguese citizenship to shield her from local charges) had been continuing secret negotiations with the Ottoman empire to become Turkish subjects; entitled to trade in Italy by treaty but exempt from heresy charges. This became somewhat less secret in 1552 when a Turkish envoy arrived in Italy to facilitate their move to Istanbul. He negotiated a settlement where Brianda received enough money to enable her to live in comfort, if not the fortune she had hoped for. That fortune went to Beatriz, indirectly. Gracia paid a hundred thousand golden ducats into the Venetian treasury to be held in trust until her 18th birthday. With that all settled Gracia and her daughter Reina (who had abandoned the false name “Ana”) swiftly departed for Istanbul. With them went her share of the Mendes fortune.

The hundred thousand ducats sitting in Venice made the thirteen year old Gracia la Chica (as Beatriz now called herself) one of the most eligible young women in Europe. The nobles of Venice immediately began negotiating over which of their heirs would be married off to her to gain the fortune. The House of Mendes were unwilling to give up on either Gracia la Chica or her dowry, and did their best to persuade Brianda to take her daughter and move to Turkey. When she declined, they took more direct action. With the assistance of his brother Bernardo [4] and the cooperation of Gracia la Chica (who didn’t want to marry the man the Venetians had chosen for her) Joseph Micas “kidnapped” her and eloped.

The couple hoped to make it to Ferrara, where they would hopefully be safe. To get there they had to cross the Papal States, and while doing so they were arrested in the town of Faenza. At the nearby city of Ravenna there was a hearing where Joseph declared that he and Gracia la Chica were married, and that the marriage had been consummated. (The first was probably true, and the second was probably a lie intended to stop the marriage being annulled.) While his wife was held under armed guard in Ravenna, Joseph fled the city and made his way to Rome to plead his case. Meanwhile the Council of Venice sentenced him, Bernardo and the others involved in the affair to banishment and death if they returned. They also levied huge fines on them, which they gleefully appropriated from the Mendes holdings in the city.

Joseph was unsuccessful in getting Rome to recognise his marriage, and while he was doing so Gracia la Chica and Brianda were facing a new peril back in Venice. The Inquisition had taken advantage of the confusion and recrimination over the “kidnapping” to begin investigating suspected “Judaizers”. In the course of the investigation, both Brianda and Gracia la Chica came under suspicion. First the two woman declared their Christianity to the Inquisition (with Gracia la Chica saying that she wanted to be a nun), then they declared their Judaism to the Council of Venice. The Council decided to expel them from Venice, and they moved to Ferrara. Brianda died shortly after they arrived there, her ill-health not being up to the disruption of the move. Since Gracia la Chica’s marriage had been anulled, after a year of mourning she was free to remarry to the man of her choice; which turned out to be the other man who had “kidnapped” her, Bernardo.

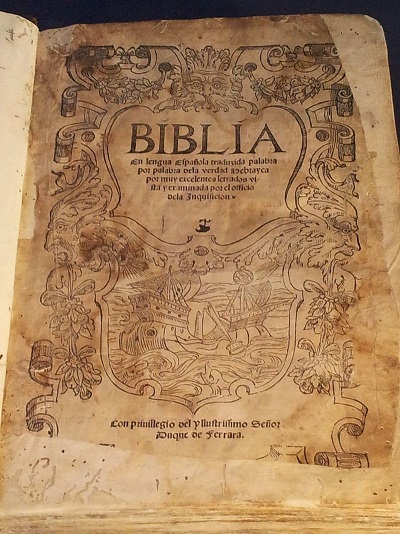

Bernardo and Gracia la Chica remained in Ferrara, which was one of the few places in Italy that was openly (and legally) tolerant of Jews. Though Gracia the elder (known now as Gracia Nasi) was not in Ferrara at this time, she remained active in supporting this island of freedom. This was most evident in her sponsorship of the “Ferrara Bible”. The Ferrara Bible was a unique work designed to illustrate the connection between the Jewish and Christian faiths, a retranslation of the Hebrew canon of books known as the Tanakh that is almost (but not quite) equivalent to the Old Testament. The book was published in both a “Christian” and a “Jewish” version, though the main difference was in the dedication. The Christian version was dedicated to the ruler of Ferrara, Duke Ercole. The Jewish one was dedicated to “Donna Gracia Nasi”. Sadly throughout the 1550s the growing “Counter-Reformation” tendencies of the Popes led to all religious tolerance being forced down, and Bernardo and Gracia la Chica decided to follow their aunt to Istanbul. Given the fortune attached to them this proved controversial, and it wasn’t until 1558 that they were able to negotiate their passage to Istanbul.

Gracia Mendes Nasi’s connections and wealth made her an immediate force to be reckoned with in the Ottoman Empire. In Istanbul she swiftly became a leader of the local Jewish community, financing the building of several synagogues. Under the Imperial regime Jews were classified as “non-Muslim subjects”, which basically meant that they paid some extra taxes and that was that. Unlike in Christian Europe they were free to organise their own communities and run their own affairs, as long as they respected the structure of the Ottoman bureaucracy. And paid their taxes, of course. The same was true of Christians, though the Jews had the advantage of their loyalty being considered more reliable because the Ottomans were granting them sanctuary.

Joseph Micas had followed Gracia and Reina to Istanbul in 1553, and the following year (having failed to stop his marriage to Gracia la Chica being annulled) he married Reina Mendes. This cemented his position as Gracia’s heir while also providing a great social occasion for Gracia to show off her wealth and impress the people of Istanbul. She made the politically astute move of cultivating Prince Selim, the heir apparent to Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. Though there was a lot of intrigue and conflict over who would succeed the Sultan, Selim would eventually win out and take the throne in 1566. When he did, he remembered who his friends had been back when things were uncertain.

Gracia continued to exert influence back in Europe, of course, as the spice trade was still dominated by the House of Mendes. This influence was needed, as dark times were coming for Jews in Christendom. Pope Paul IV, who ascended in 1555, was a notorious anti-Semite. He issued a Papal Bull which, among other things, ordered that the Jewish community were only allowed one synagogue per city. This led to seven being demolished in Rome alone. He forced Jews to wear yellow hats to mark them out when they left their ghettos, and they were severely restricted in the matters of trade and residence. He also established a ghetto in Rome for the first time in its history, one that would remain until near the end of the 19th century.

This prejudice fell on the Conversos as well, of course. Even those who had fully converted to Christianity were still considered effectively Jewish because of their ancestry, and they were subjected to the same restrictions. (Unsurprisingly this did then drive many of them back to their Jewish faith.) The restrictions hit the Mediterranean traders hard, as many cities which had prospered through religious tolerance suddenly began to crack down on them. The biggest impact was the trading city of Ancona, which had offered a sanctuary for Conversos for the last twenty years or so. There were mass arrests and twenty-four people were burned at the stake, with many others being imprisoned or made into galley-slaves. Among those executed was Jacob Mosso, Gracia’s agent in the city, and this was part of why she led a boycott of Ancona to try to get those imprisoned freed. The boycott was controversial, with many fearing it would imperil the Jews remaining in Ancona. As a result it eventually collapsed.

Gracia did her bit for the refugees from Europe as well by ensuring that Istanbul was a welcoming place by ensuring that both synagogues and employment were available for them. Her daughter Reina became involved in publishing, along with Abraham Usque (the translator of the “Ferrara Bible”) who had moved to Istanbul. Part of Gracia’s efforts to resettle these refugees involved getting permission from Sultan Suleyman to resettle the ancient Jewish cities of Safed and Tiberias. (This effort has led to Gracia being considered a fore-runner of the Zionist movement.) Both Gracia and Joseph were involved in this project, with Joseph attempting to establish Safed as a silk production centre to rival those of Italy. This was a mixed success at best, with local Muslims resisting (sometimes violently) attempts to rebuild the city. They were also in a part of the Ottoman Empire that was the site of ongoing rebellions by the Druze, [5] who would demolish the city in the 17th century.

By the late 1560s Gracia Mendes Nasi had retired from public life, and control of the House of Mendes had passed to her son-in-law and heir Joseph Nasi. In that role Joseph negotiated court life, leveraging his old friendship with Maximillian (now Holy Roman Emperor) to negotiate a peace between the Empire and the Ottomans as well as provoking a war with his old enemies Venice that ended with Cyprus in Turkish hands. When Gracia passed away in 1569, she must have been confident that she had left her legacy in good hands. Unfortunately Joseph proved less adept without Gracia’s advice, and over the next few years his fortunes waned. The death of Selim II in 1574 was the end of his influence in the Ottoman court, and his attempts to rebuild bridges in Europe came to nothing. He died in 1579, ten years after Gracia, leaving no heir behind him. With his death the House of Mendes, once the Pepper Kings of Europe, fade from the pages of history.

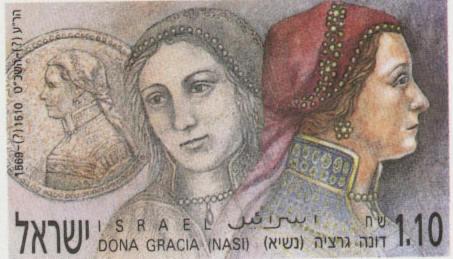

While Joseph Nasi remained a solid footnote in the history of Ottoman/European relations, Gracia Mendes Nasi was almost immediately scrubbed from the historical record. This was less due to any directed malice and more a result of historical misogyny and anti-semitism. Immediately after her death she was eulogised and commemorated by the Jewish community, but by the 20th century she was almost forgotten. Gradually though she emerged into the light through the joint efforts of Jewish and feminist historians. The story of Dona Gracia Mendes by Bea Stadtler in 1969 was a seminal work in bringing Gracia back into the view of historians, while Marianna Birnbaum’s 2001 book The Long Journey of Gracia Mendes re-established her on a solid academic footing. In the 21st century Gracia has enjoyed somewhat of a renaissance, with a museum dedicated to her life opening in Tiberias and with the Turkish government sponsoring events to honour her as a historical symbol of the sanctuary offered by the Ottomans. Both New York City and Philadelphia have declared days in her honour, and she’s even appeared as a major character in a popular Turkish TV drama about the court of Suleyman the Magnificent. It may have been a long time coming, but it seems that nowadays Gracia Mendes Nasi is finally getting the recognition she deserves.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] Gracia is the literal Portuguese translation of Hannah, which means “Grace”, and it’s the name that she chose for herself when she had the freedom to choose. As such to avoid confusion it’s what will be used throughout this article. Similar cases of people with multiple names will use the name most often used to refer to them.

[2] Partially as a result of this, Antwerp would lose its position as the financial capital of Europe over the next twenty years.

[3] Though Judaism itself wasn’t considered a heresy by the Catholic church, abandoning Christianity or falsely professing it definitely were.

[4] Bernardo’s Hebrew name was Samuel, though he rarely used it.

[5] A separate religion which splintered away from Islam in the 11th century, and which is still practiced in the Levant region (especially Syria) to this day.