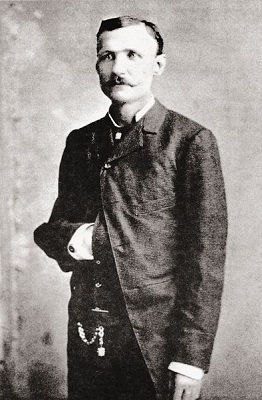

Luke Short, Gunfighting Gambler

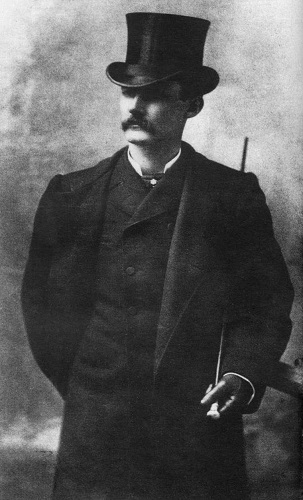

During his lifetime, many men underestimated or ignored Luke Short. He stood less than 5’6” tall and seemed like a natural target for the type of bully that frequented the American “Wild West” period. But those who tried to take advantage of Luke soon learned their mistake, sometimes fatally. Though he was only ever in a handful of gunfights, he gained a reputation as a deadly man to cross.

Luke Short was born in 1854 in Polk County, Arkansas. He was part of a large family, right in the middle of nine children born to Hetty and Josiah Washington Short. When he was five years old his family moved to Texas, where Josiah purchased a large amount of land relatively cheaply in order to raise cattle there. Part of the reason why the land was so cheap was because this was still “unpacified” territory, and when the local militia headed off to fight in the US Civil War then raids by Native Americans on the ranches became more common. In 1862 the eight-year old Luke saw his father nearly killed in a raid, though his elder brother managed to drive them off with a rifle Luke brought him.

Luke never had any real formal schooling, being expected to work on the ranch from a young age. In 1869 he officially began working as a cowboy, at the age of fifteen. Over the next six years he made several cattle drives from Texas to Kansas, and like a lot of those on these trips he took the opportunity to make some money for himself outside of his wages. He did this both by buying cattle that were included in the drive and by taking trade goods (like cotton) with him on the trip. And it was in the town at the end of that trip, Abilene, where Luke Short first began to make a name for himself as a gambling man.

Luke moved to Kansas for a year in 1873 before returning to Texas. In 1876 he headed to the Black Hills in Nebraska, which at the time was in the middle of a gold rush. Luke didn’t have the temperament for mining but he seems to have found work as a hired gun. There was plenty of work to be had, though whether Luke earned his money defending against bandits or by being a bandit is a matter of debate. There are stories that he was arrested by the army for selling whiskey to Native Americans and escaped, but these seem to be based entirely on a story of dubious veracity written by Bat Masterson over thirty years later. In fact Luke’s main involvement with the army during those years was not being arrested by them, but working for them.

In later years Luke was dubbed “the bravest scout in the US Army”, but in fact his military career lasted less than two weeks in October of 1878. He was employed to deliver a message to Major Thomas Tipton Thornburgh, who was tracking down a group of Cheyenne who had gone “off reservation”. His arrival was credited with saving the Major’s company of 500 men, as his own scouts didn’t know the territory and the Major didn’t know he was probably walking into an ambush. Luke stayed with the Major until he had recaptured and re-imprisoned the Cheyenne on the reservation, and then he quit the army having had enough of it to last him a lifetime.

In 1879 Luke made his way to the town of Leadville in Colorado, a mining town where there was a lot of money from silver mining changing hands. Once again Luke had no interest in mining though. He first came to town as a hired gun but soon decided that becoming a professional gambler was more to his taste. “Faro” was the game of choice at the time, rather than poker. (Faro essentially involved drawing through a deck of cards and wagering whether each card would be higher or lower than the first one drawn.) And it was over a game of faro that Luke got into his first recorded gunfight, when another player tried to claim a bet that Luke had placed. The nameless cheat (at least, according to Luke) had some reputation as a gunslinger, but Luke drew faster and shot him in the face. The bullet only wounded him in the cheek, but it was enough to cement Luke Short’s reputation as a man not to be crossed.

There are darker rumours involved with Jim’s time in Leadville, including stories that he robbed some stagecoaches to supplement his income. Whatever he was up to though, Luke left it out of his entry on the 1880 census forms. He recorded his job simply as “clerk”. Shortly after that he returned to Kansas where he was arrested for swindling a man at cards but released without charge. Then in late 1880 he made his way to a town that remains synonymous with stories of the Old West: Tombstone, Arizona.

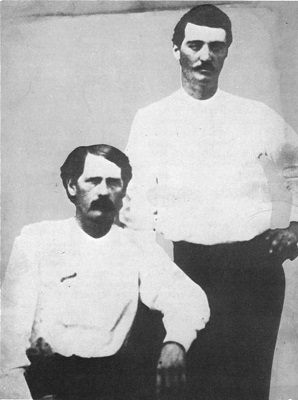

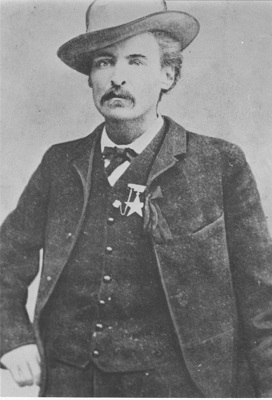

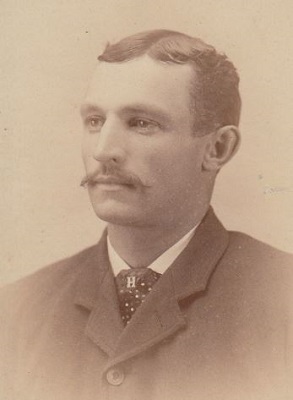

Tombstone was another silver mining town, and it was where Luke met and made friends with three other professional gamblers; Wyatt Earp, William H Harris, and Bartholomew “Bat” Masterson. Earp, of course, is well-known nowadays for his exploits as a lawman, though most of his reputation is based on a posthumous biography that played fast and loose with the truth. Bat Masterson was prepared to play fast and loose with the truth on his own account; he became a writer in 1902 and wrote stories both of himself and of the gunfighters he had known (including Luke). This of course cemented Bat’s own reputation as a Western legend. Harris is the least famous of the group, though that might be because he was the most successful of them (and so least needed to inflate his reputation).

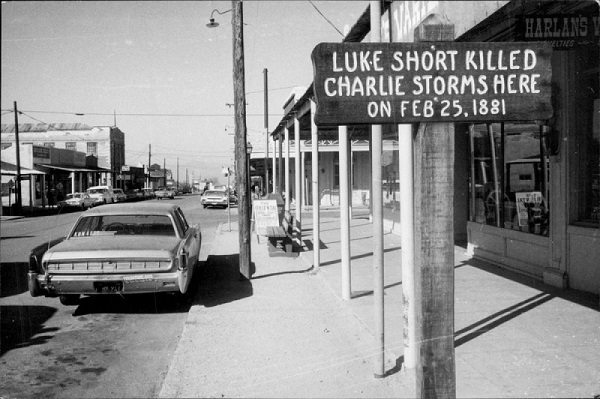

Harris was one of the manager/owners of the Oriental Saloon in Tombstone, and he persuaded his partners to hire his friend Wyatt as a faro dealer. Luke got a job at the Oriental as a “lookout”, keeping an eye out for cheats. (Nowadays this job is called “pit boss”.) Bat Masterson had the same job, which was how the men all met. Another friend of Bat’s was a gambler called Charlie Storms, who was well-known as a gambler and a gunfighter. Charlie was also a drinker, and so when Luke took him to task for his behaviour in the Oriental he didn’t respond well. A lot of the trouble Luke ran into was down to his height; he was only five and half feet tall and slimly built. He didn’t look like a fighter, so men like Charlie Storms assumed they could push him around. Luke Short was not a man to take that type of treatment well, as Charlie found out. Accounts vary how it happened, but the argument ended with the two men in the street in front of the saloon. Charlie was the first to go for his gun, but Luke was the first to fire. Charlie Storms was shot through the heart and died. The coroner cleared Luke on grounds of self defence. And Tombstone learned a lesson: don’t mess with Luke Short.

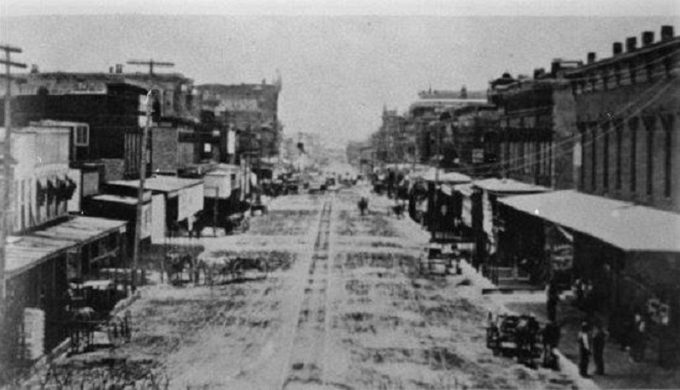

After the Storms affair Luke decided to leave Tombstone and move to the unofficial capital of the western frontier: Dodge City. He took a job as a faro dealer at the Long Branch Saloon, which was owned by William H Harris. By now Harris was one of the richest men in Dodge City; rich enough to be one of the co-founders of the Bank of Dodge City. Luke did well himself, though not as well as Harris. He prospered enough that when Harris’s partner Chalk Beeson sold his share in the Long Branch then Luke was the one who bought it. This gave him some responsibility, as Harris was about to get busy with politics and run for mayor of Dodge.

The reason for Harris’ sudden interest in politics was down to the man running against him: Lawrence Deger. Larry Deger had been Dodge City’s first marshal and had a reputation for upholding the law despite opposition. At one point he had arrested a friend of the mayor at the time, and the mayor had tried to fire him. Larry responded by charging the mayor with obstruction of justice. It took the city council’s intervention to bring peace between the two, and Larry stayed on as marshal. Unsurprisingly he was running for mayor on a “reform” platform; to clean up Dodge City. Luke and Harris liked Dodge City just as dirty as it was, which was why Harris ran against him. Unfortunately for the two saloon-owners, they lost the election. Larry Deger became mayor in April 1883.

Within weeks of becoming mayor Larry took aim at the Long Branch Saloon. Two ordinances were passed, one for the “suppression of vice and immorality” and another to “define and punish vagrancy”. Based on this three women working at the Long Branch were arrested. Luke claimed they were singers, while the lawmen claimed they were prostitutes. Whatever their profession, it was notable that no other saloon was raided. Also notable was later that evening when Luke met a policeman named Louis Hartman. The two exchanged heated words, followed by hot lead. Neither was injured but Luke was arrested. Five other professional gamblers were swept up in the following days.

Rather than being put on trial, Luke and the other gamblers were simply taken to the train station and ordered to leave town. [1] This extra-legal punishment lends credence to tales of other excesses of Deger’s “vigilance committee”; including threatening a lawyer who tried to represent one of the men with a shotgun and ordering the local correspondents of national newspapers like the Chicago Times not to cover the story. As a result of this Luke had a lot of sympathy in Kansas City, and he also had plenty of friends. One was another former marshall of Dodge, Charlie Basset. Another was William Petillon, a county clerk. Petillon helped Luke present a petition to Governor George Glick. This led the governor to carry out his own investigation, and he wasn’t happy with Deger overstepping his authority. In his eyes it was simply a war between rival saloons where political office was being abused.

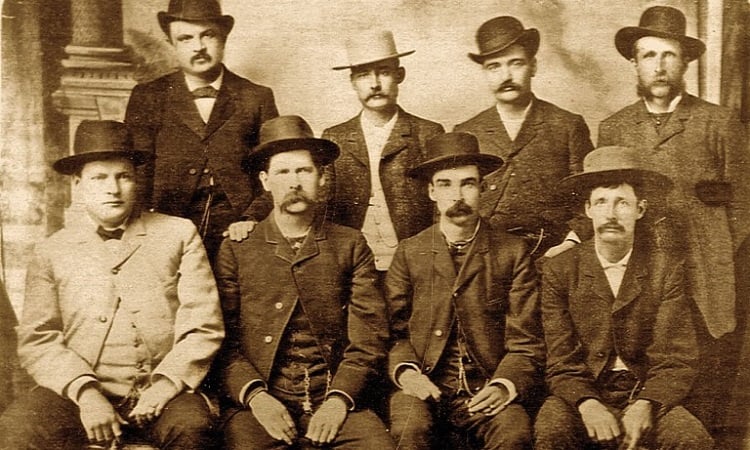

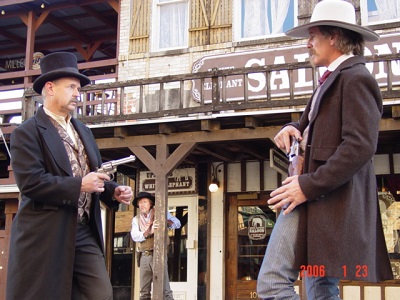

In addition to his legal actions, Luke began to gather his friends about him. Bat Masterson and Wyatt Earp rallied to their friend’s side, of course. And Wyatt brought his friend Doc Holliday along too, of course. By now the papers were calling this the “Dodge City War”. When Luke returned to Dodge with these friends, people expected shots to start flying. But the governor exerted his influence, as did someone equally powerful: the president of the Santa Fe railroad. With a militia company on hand to enforce the peace, the two sides met and agreed to drop the matter. The following day Luke and his friends posed for one of the most famous photos of the old West, one which has become known as “the Dodge City Peace Commission.”

Despite having settled matters, Luke didn’t really feel welcome in Dodge any more. The old wild days were beginning to fade and Kansas was starting to get more civilised than Luke preferred. He and William Harris began to investigate moving to Texas, and in November of 1883 they sold the Long Branch saloon. Less than six months after he had fought a bloodless war to get back into Dodge City, Luke Short left of his own free will.

Luke’s new home was Fort Worth, a town at the terminus of the railway lines that was the main destination for Texas cattle drives. This made Fort Worth one of the biggest towns in Texas. It was the home of “Hell’s Half-Acre”; twenty-two thousand square feet of saloons, cathouses, hotels and gambling dens. One of the most famous was the White Elephant saloon. It opened originally as a small restaurant in early 1884 and quickly failed. The building was bought by three Jewish businessmen who opened it as a saloon, but the prejudice they faced in the local community made them realise they would never be allowed to make a success of it. So they sold it to a partnership consisting of James A Reddick, Jake Johnson and Luke Short.

The new ownership took over the two adjoining businesses to expand, making the White Elephant one of the largest saloons in Texas. Luke was brought on as a partner because of his knowledge of gambling, and he was given full control over that side of the business. He quickly made the White Elephant one of the most respectable gambling establishments in the city. Of course, gambling was illegal in Texas. But like most establishments the White Elephant simply paid its annual fine as if it was a license fee, and no further action was ever taken.

Another partner was Jake Johnson, a former cattleman who now lived off his investments and his stable of prize racehorses. He introduced Luke to turf betting, which led to Luke partnering in a racecourse in Fort Worth. Luke also got into boxing, thanks to his friend Bat Masterson. That led to a bit of a personal disaster, after he was asked to referee a fight between “Kid Bridges and the “St Joe Kid”. Kid Bridges knocked the St Joe Kid out, at which point his second (assuming the match was over) ran into the ring. Since time had not been called this was a foul and technically the St Joe Kid won the match. Tempers were high, and whatever decision Luke made would have been the wrong one. He sided with the St Joe Kid, and was dogged by rumours afterwards that it was a crooked call.

1887 was a significant year in Luke’s life for many different reasons. The first was his brother Henry, who shot and killed a man in the town of San Angelo. Most of Luke’s family lived in the town, and there were suggestions the killing was over a rivalry between two meat markets. Henry fled town after the killing, heading to the only man he knew who could help him: his big brother Luke. Unfortunately Luke was short of cash at the time. (He was also facing serious fines for trying to run a gambling ring at the annual Dallas fair the year before.) So he was forced to sell his share of the White Elephant, though this was intended to be a temporary thing. In fact he was still the gambling manager of the saloon, which was what brought him into conflict with Jim Courtright.

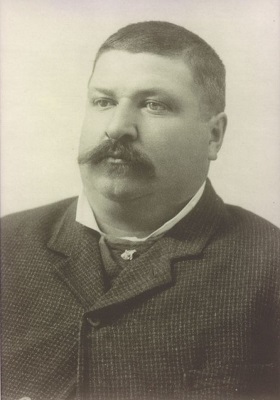

Jim Courtright had been the city marshal of Fort Worth ten years ago, when he gained a reputation for dispensing law right from the barrel of his gun and managed to cut the murder rate of the town by half. He didn’t just kill criminals, though. Rumour had it that several of the “criminals” he killed in “self defence” were business owners who refused to pay their protection money. After he lost the 1879 election he left town and moved to New Mexico, where he was hired by the American Valley Cattle Company. He was one of six men who murdered a pair of ranchers that refused to sell the company their land, after which he fled back to Texas. By 1887 he had returned to Fort Worth, where he was running a “detective agency” and trying to re-establish his old protection racket. Of course, this new “biggest saloon in Texas” was a prime target for a shakedown. Or so he thought.

Jim began doing the rounds of the various saloons, offering to have his agency act as “security” for them in exchange for a percentage of the profits. Some of the smaller ones gave in, but Luke refused. He did offer to pay Jim a flat fee to stay away, but Jim wasn’t willing to do that. Aside from everything else, he knew having his men publicly guarding the White Elephant would boost his protection racket while letting Luke get away with defying him would hurt it. That was what led to Jim standing outside of the White Elephant wearing two pistols and calling for Luke Short to come out.

Jake Johnson was in the saloon at the time, and he was an old friend of Jim. He managed to calm him down before Luke came out. The two men exchanged words, but matters were tense. Suddenly Jim thought that Luke was drawing on him, and went for his gun. Luke claimed that he’d been adjusting his clothes and Jim had made a mistake. Whether that was true or not, Luke was the first to fire. One of his bullets struck Jim in the hand, which might be why he never got a shot off. Another went into Jim’s shoulder. The third struck him in the heart. By the time the local policemen made it to the scene, he was dying and he died soon after.

The inquest was held the next day, and stands as a testament to the problem with eyewitnesses. One said that Luke shot Jim five times, another said four. Neither was consistent with the medical evidence or the number of bullets fired by Luke’s gun. There was evidence given that Jim had told multiple people that he planned to kill Luke Short that night. The only uninvolved eye witness was Jake Johnson, who was friendly with both men, and he backed up Luke’s story that Jim went for his gun first. Based off this the state decided that the case for self-defence was strong enough that they never brought the case to trial.

Luke’s brother Henry also avoided having his case go to trial, though the reason for that isn’t recorded anywhere. Regardless, Luke decided not to buy his stake in the White Elephant back. Jake sold it instead to the Ward brothers, who had already bought Reddick’s stake and Jake’s original stake. With that the original White Elephant company was dissolved. Luke had other things on his mind, anyway. In March of 1887, just over a month after Jim Courtright was shot, Luke headed to the town of Oswego where he got married.

Harriet Beatrice “Hattie” Buck was a 23 year old beauty from the town of Emporio in Kansas. Some contemporary accounts described her as “the daughter of a banker”, but her father (who was dead by 1887) had actually been a carpenter. She met Luke under “romantic circumstances”, though the details were not recorded. After the wedding Hattie and Luke made a brief stop in Fort Worth before heading on to Hot Springs, a city in Arkansas. As the name suggests this was a popular health destination, and the fact that the couple stayed there for two months is sometimes taken to mean that Luke was beginning to have health problems.

By the time they left he was apparently recovered though, and after traveling to a few more destinations the couple headed to New York State to attend another wedding. Luke’s old business partner and friend William Harris was also getting married, and after the wedding he took Luke and Hattie to tour the racing circuits of New Jersey and New York. They continued their travels through the summer, and returned home to Fort Worth at in September.

There was trouble waiting for Luke back in Fort Worth, though. He was still the gambling manager at the White Elephant, but he had aroused resentment among the other gambling houses by switching from Faro to a newer game called Keno. (Keno is a game like a cross between bingo and a lottery, where players mark numbers on a card and then win based on how many of those numbers are drawn.) The game cut the faro dealers out of the equation, which didn’t sit well with them. The reformer Sheriff also tried to ban it. It seemed like in Dodge City, the writing was on the wall for Fort Worth as a wild town.

Luke was unhappy when the owners of the White Elephant decided to close down their gambling operation rather than continue to face the legal heat, and on December 12th he got drunk and angry. Angry enough to pull a pistol out of his pocket and fire it at the floor. That got him arrested and up on charges for carrying a gun. Luke’s defense was that he had received multiple letters threatening his life for running a keno game, which got him cleared on appeal. After that he decided it was probably time to get out of the saloon business.

In 1889 Luke Short started spending more time north, in the city of Chicago. He still owned a house in Texas and none in Chicago, but the Leland Hotel became his home away from home. He was a “silent partner” in several business ventures, but publicly his main concern was horse racing. He tried to break into the boxing promotion game, setting up a fight back in Fort Worth, but then one of his fighters was arrested. He’d been participating in a “take on all comers” challenge in Dallas and had accidentally killed one of his opponents. Though he was acquitted, it derailed Luke’s plans to the extent that he never managed to arrange the heavyweight championship fight he wanted.

During this time Luke took a trip with Jake Johnson to visit a stud farm in Tennessee. While they were there they took a trip to Memphis to play some cards in the gambling houses with a few friends. Luke and company won big, and walked away with several thousand dollars. Charles Wright was given the money to look after, but didn’t bother putting it in the hotel safe. Naturally he was robbed of every cent. The other gamblers blamed him for the loss and he was forced by a court to pay them back the missing money. Given how much Wright hated him after this it seems likely that Luke was the one who insisted he pay the money.

Wright definitely seems to have harbored a grudge out of proportion to the incident. He was arrested in Fort Worth for threatening one of the other players (a man named Bud Fagg) with a pistol. Luke was more concerned with his boxing promotions though. There was a chance that boxing might be outlawed in California, which would drive the sport mainly into Texas and give Luke a shot at arranging the big title fight he’d always wanted to run. He’d never get that break, though.

Exactly what went on between Luke Short and Charles Wright over the course of 1890 isn’t clear, but by the 23rd of December matters had clearly reached breaking point. Around half past nine Luke arrived at the Bank Saloon in Fort Worth, which was run by Charles Wright. He grabbed a waiter and used him as a human shield when he burst into the gambling room with his pistol drawn. When he ordered all the gamblers to leave they obeyed, and he let the waiter go with them.

Charles Wright was in a storeroom down the hall, and as Luke headed towards it a friend of his named Louis de Mouche came up the stairs and asked him to leave off before he was hurt. Before Luke could answer Charles Wright stuck a hand holding a pistol out of his door and fired. He missed, but Luke didn’t. He struck Charles in the wrist and moved to take advantage of it. As he went down the corridor Charles fired a shotgun through the door. Alternatively, the shotgun blast came first and Luke fired after he was struck. Either way, Luke was badly injured and fled the scene.

The police arrived while Luke was being treated. He’d been injured in the left leg and hand. His thumb was gone, and two of his fingers were likely to follow it. The muscles on his leg were also badly injured. Wright was found back at the scene, and taken to a different doctor for treatment. He was well enough to be taken down to the county jail. Luke was too badly injured and was guarded at the doctor. Both men were bailed for $1,000.

Luke was bedbound for months, as his injuries were severe. In part this was also due to ongoing health problems, as he’d been suffering from fatigue for the last few years. Still, papers reported his wound as “near-fatal”, and in that pre-antibiotic age if he had got an infection they probably would have been. He was well enough by May to head north to Chicago for the races. There he was a subject of curiosity as the famed Western gunslinger, with tall tales aplenty about his proficiency with a pistol.

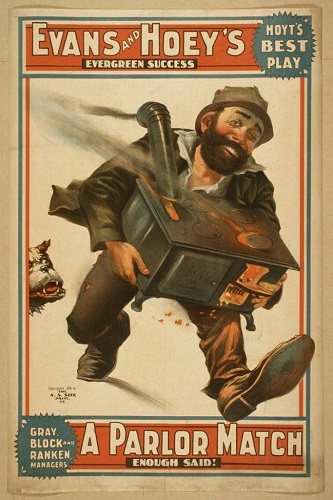

Luke didn’t match the tales in appearance, though, which once again nearly had fatal consequences. A man named Singleton got into an argument over a girl and lost, then decided that the short guy at the hotel bar was someone he could insult to make himself feel better. Luke knocked him down, kicked him several times and then threw him out into the street. Then he went upstairs to get his gun in case Singleton came back. As he was descending the stairs a comedian named William Hoey, who had the same cut of beard as Singleton, was coming in the door. Luke charged the man but a brave hotel clerk managed to get in the way and explain. Luke apologised and the two men retired back to the bar, where the comedian forgave him over a few drinks.

Luke’s trial for the attempted murder of Charles Wright took place over a year after the incident, on the memorable date of February 29th 1892. Though Luke had been the one to incite the incident, there was no proof that he had fired before he was hit by the shotgun blast. (The prosecution claimed he had, but could not prove it.) As a result he was convicted only of “aggravated assault”, and fined $150. Wright’s court case had a similar conclusion.

By the beginning of 1893 it was becoming more clear to everyone that Luke Short was seriously ill. The doctors of the day diagnosed him with “Bright’s Disease”, which isn’t actually a disease. It was how the 19th century categorised the effects of kidney failure. We don’t know why Luke’s kidneys were failing, but it was the beginning of an inevitable end. High blood pressure was one of the symptoms, which the doctors tried to treat with blood-letting. That simply weakened him, of course. In September he and Hattie went on a trip to Geuda Springs in Kansas hoping that the waters might effect a miracle cure. They did not. Luke died on the eighth of September at the age of 39.

The Texas newspapers covered Luke’s death, but its unspectacular nature meant that it was largely ignored by papers outside the state. Unlike many of his contemporaries he never really became a “legend of the West”. The closest he came was as the cause of the “Dodge City War”, and even then that was only because of the the involvement of Bat Masterson and Wyatt Earp. In fact his only TV show portrayals come in episodes of shows about the two more famous men. If he had lived, perhaps he would have found a way to turn his reputation into fame just as Bat did. As it is, he’s faded away into relative obscurity.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] This may be the origin of the phrase “get out of Dodge”, though it was popularised by the 20th century TV show Gunsmoke.