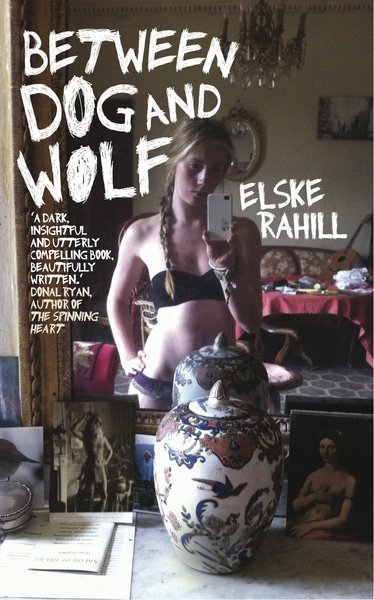

Between Dog and Wolf | Elske Rahill interview

Stephen Totterdell interviewed Elske Rahill following the release of her novel Between Dog and Wolf.

Stephen Totterdell interviewed Elske Rahill following the release of her novel Between Dog and Wolf.

The book persuades the reader to feel physical discomfort. Through its frequent “close-readings” of the body, the text causes the reader to feel self-conscious, fully aware of their own body. Could you talk a little about what you were aiming for with this technique, and do you think it achieves a different effect in different kinds of readers?

I am interested in how the body informs the rest of us; how the skin we are in can alter our perceptions of each other and of the world; how we can objectify our own bodies as both men and women and how this shapes the inner and outer world for us.

I never really chose this approach as a technique, or at least I didn’t think of it like that. It was simply my way of understanding or creating the characters. I tried to literally get under their skin and understand their world starting with the physical sensations of being them.

Some readers found it pretty repulsive, which is fair enough. If you are squeamish about the body it might be unpleasant to wriggle around in someone else’s skin like that. I suppose gender might play a role in what effect these scenes have on people; whether they identify with the looker or the looked at… and age, I suppose. There are periods in life when the body seems central, and other times when that kind of experience seems foreign and might be hard to identify with.

I do try to focus on communicating when I write, but at a certain point you have to stop wondering about the reactions of readers. I have no way of really knowing what effect this kind of writing has on the readers, except to ask, and all reactions have been different so far. The only thing I found pretty shocking and, I have to admit, it upset me and made me feel that I really had failed as a writer, was when the writing was described as ‘sexy.’ What can you say to that? It made me despair.

Would you call yourself a political writer, or beyond that: do you agree with the distinction between “political writer” and “writer”?

I am about to say I don’t agree with the distinction, but what other way can you describe what you mean? The distinction is necessary, but of course I think all writing is political, none more so than the kind of writing that is apparently politically unaware. Work that reiterates its culture, like a lot of chic lit, teen romances etc., are probably all the more insidious for their apparent innocence.

I think I am a feminist writer, and therefore political. Being aware of this can thwart my writing sometimes I think, because, much as I may talk the Marxist talk, I do believe that there is a sort of artistic force, or spirit, that is not conscious or political except in so far as the existence of all art is a sort of human assertion. So when I write I am torn between a will to write for reasons I don’t understand, and a constant critique of what I write as reiterating or subverting systems I do or don’t condone. Once you are aware in this way it becomes impossible to simply write as the impulse takes you, to be an unfettered ‘artist’ type being. The only way I can find to straddle these two horses is to ignore the internal critique while I write a first draft. Then, when this draft is done. I can read it and try to understand what it was I was unconsciously trying to do, or why I needed to write this. Then there is room for a more politically conscious redrafting and redrafting, but I have to obey the impulse first, and wonder about it afterwards.

I don’t exactly set out to be a political writer, but it is impossible not to be, and much worse to pretend not to be.

The use of the second-person perspective for Helen is unusual. Why did you go with this?

It seemed impossible to write Helen in the first person – her own self identity was so caught up in an objectified version of herself. Hers is a world of mirrors and the only way to really write her seemed to be in the second person.

The minute changes to our identity that come about when we move city, go to college, enter a new relationship, socialise with a different group and so on are all articulated really well – do you think there is a growing knowledge in society of this kind of social performance?

I don’t know. I certainly think a lot of gender theory has been barking that idea up for some time, but whether there is a growing awareness of it I don’t feel qualified to say… I am a bit of a hermit these days and no expert on social or cultural trends. But I will try to answer:

When you look at the music videos about; there must be something bubbling up through the cultural psyche that is increasingly aware of identity as performance. And technology changes things a lot. There is something very comforting about essentialist readings of the body, but when the conscious being makes choices that alter the body radically, that position is thrown into orbit and we are forced to face the far more complicated reality of social performance, culture, the body etc.

The notion of attending college and becoming alienated from your family and friends through education is an interesting one. I read an article by an academic recently, in which she talks about coming from an underprivileged family and becoming a professor. Many of her points of reference have changed so that it is difficult for her to go home; she feels that she doesn’t quite fit in anymore. It does challenge the essentialist idea that there is a “self”, and I think the book breaks this idea down quite articulately. Do you have one or two major identity or gender theorists you feel have influenced your work?

The notion of attending college and becoming alienated from your family and friends through education is an interesting one. I read an article by an academic recently, in which she talks about coming from an underprivileged family and becoming a professor. Many of her points of reference have changed so that it is difficult for her to go home; she feels that she doesn’t quite fit in anymore. It does challenge the essentialist idea that there is a “self”, and I think the book breaks this idea down quite articulately. Do you have one or two major identity or gender theorists you feel have influenced your work?

Not really. I wrote the first draft of this book as a lazy undergraduate. With all the ideas knocking about the arts block I’m sure a lot of it made its way into the book, but not in any conscious way. At that time I couldn’t have linked ideas to names of theorists. Much of my thinking came from other fiction.

Then again I am fascinated with Ettinger’s work; with the possibilities outside our cultural idea of subjectivity and Rupert Sheldrake’s notions of morphic resonance… all of these current ideas that open up identity in a terrifying and potentially revolutionary way.

I like the idea that you can live in France and write. Do you find that your environment has an effect on your writing, or your view of literature?

Definitely. I have literally no literary frame of reference here. It means I can really focus in on whatever I am writing and become submerged in the characters and their world. I have a terrible tendency to see literary works in isolation. I pick up Annie Proulx or Philip Roth without really placing them within a context of other work or how they relate to one another. It is sort of childish and unacademic. This is certainly worsened by being quite isolated from an literary culture. I live in a tiny village. There isn’t much hanging about cafes talking about poetry…

Can you talk a little about some of your favourite European novels?

I’ve just finished reading Suite Francaise. I could not separate it from the writer and her life and I was simply awed by her human capacity to understand the other at a time when dehumanisation was the overriding force. It reminded me of one of the fundamentals of writing, which is empathy. It’s something that is easy to forget when you get caught in all the political implications; yet here is a deeply political book that is not political at all; an intensely humane portrait of people caught up in horrendous forces. The book was raw and unpolished, which made it all the more intimate. The experience of reading it felt half voyeuristic and half ennobling. It left me really humbled, not as a writer but as a person witnessing the immense human capacity of another.

Does living in France then cause certain social performances, both in France and in Ireland? When I lived in Germany a lot of people associated me with “Ireland”, and I felt a certain pressure to represent the country that I had never felt before.

I live in a tiny village with an aging population and a very patriarchal culture. I am known as my partner’s ‘femme’ and my children’s ‘mere.’ I have a circle of friends with whom this is not the case, and amongst them I don’t really feel like the ‘Irish woman,’ though I am told the villagers call our family ‘Les Irlandais’ and I am supposed to be offended by this, but I really don’t mind. Somehow, not being from here, none of this bothers me much. I am content to have a few close friendships and to be perceived through this terribly patriarchal gaze. I feel an almost documentarian detachment from it. If anything, being Irish in France allows a certain freedom. I excuse everything by being Irish. In Ireland we do not mop the floor twice a day or iron our husband’s shirts; in Ireland men share the housework, in Ireland we all have dishwashers… and so on. It is not terribly responsible of me but it makes life much easier.

Do you consider yourself part of a new wave of Irish writing that has certain points of reference in common? What are those points of reference?

God no. I don’t. I’m sure from an aerial view my work has a context with other similar work but no, I really can’t see it that way. This is partly because I am totally out of touch with the ‘scene.’

Can you compare and contrast attitudes towards the arts in Ireland and France?

My experience of France is quite limited to a tiny country village. It is true that, in the absence of any art scene, being a writer neither carries the pressure nor the shame that it does in a more cosmopolitan setting. There is no theatre here, no art gallery, nothing, so the only frame of reference I have is the attitude to my own occupation. There is a really down to earth attitude here; you grow food and work to clothe your children so whatever you do is seen in that context. So I think it makes sense to people that I work as a copy editor, and my other writing is sort of met with a bewildered ‘Oh right…?’

But there isn’t that awful interrogation you get at home. ‘You’re a writer are you? What have you published? How did it do? What’s it about? Does it make money? My cousin wrote a novel…can you get it published for him?’

The book leaves out or rejects, much like Rob Doyle’s Here are the Young Men, “boring expositional detail” – which many readers expect from novels. Rather it reads very vividly. Can you talk a bit about “the state of literature” or what you would like to achieve with it in the future?

Thanks. I think I am too expositional so that is a very flattering comment! I think literature has to be different now, because there are so many new forms of communication. The pace has changed, the language has changed, and in a way you have to keep up with that. It is a wonderful thing, really, all this connectedness, but literature can be left floundering a bit. I think it needs to get a foothold in all this and really, I don’t know how it will do that, but I’m sure it will.

Without giving anything away, there is a scene in which a character accepts a beating by a group of lads for gender-related issues. He knows how the gender hierarchy works and he accepts his lot in this situation. Do you think that with the trans* movement and genderqueer characters coming to the fore, we are becoming more aware of how we can maneouvre through this hierarchy, or how we can change it?

I think we are still quite lost, I really do, but the degree to which gender is performance opens up such potential that it will have to change, simply through awareness.

You used to act, and this novel is very visual. Even its cover is obsessed with mirrors and cameras – has cinema or theatre influenced your writing or thinking at all?

I think so. More from the perspective of understanding the superficiality of identity and the effect that constant objectification and image-saturation has on identity.

Final question: what would you like to write next?

I’m almost finished my next novel. It’s about a family fighting over inheritance, but really it is about what the inheritance represents. I suppose it’s about parenthood – why we do it and what we reap for the labour; and about art, the opposite and parallel sort of lovelabour. It’s about the nature of sacrifice and love, maybe. I am terrible at talking about my own work, specially while I’m still writing it. Sorry.