How and Why to Memorise |2| INSANITY BEGINS

Last time I talked a little about the structure of Deutschland; how each verse works, what the rhyming scheme is, why the rhyming scheme is. This second installment is about everything else that isn’t rhyme, but does make the poem special.

INSANITY BEGINS: RHYME IS NOT ENOUGH, SOUND AS FLAVOUR.

So. The poem has a rhyming scheme. But rhyme is only the beginning of what GMH does with sound. He piles rhyme upon alliteration upon assonance until describing the result with any one of those names seems inadequate, and calling it by all of them is cumbersome.

Below are three short examples. These are moments which make me light up every single time I say them, with a completed-crossword-y and Radiohead-ish kind of feeling: everything is in its right place.

I dare you to speak those four lines without enjoying it. If you managed (which I don’t believe you did), try these ones:

In the first two lines, take a look at all those ‘ck’ sounds in the middle of words, some of which also alliterate. Then notice how that ‘ck’ sound moves to the start of each word with the repetitions of “Christ” and ‘christens’ in the latter two lines.

And, finally in every sense, there’s the final four lines of the entire poem:

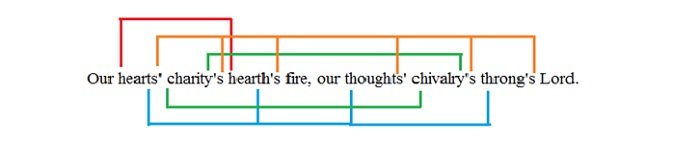

As for the last line, I felt moved to diagram all the different repetitions of sounds:

This is all very technical, so I’ll note that the content of the poem is really something too. I was raised secularly, but Deutschland made me feel like there was a beauty in the ideas of Christianity (if not the institutions of Christianity. I live in Ireland, like.)

More interesting than a glimpse of the world through Christian eyes, for me, was the way learning the poem offered me an immediate experience of my own body and the physicality of speech. Repeating such an exhaustive and exhausting array of tongue-twisters makes you very conscious that speech is a type of exertion, a type of movement. Talking is something we do all the time, for pleasure or to make people give us coffee. We can talk faster than we can think, sometimes, as you will know if you’ve ever found yourself saying something like this:

-Yeah and then I thinged it with the stuff, y’know, the stuff, it’s that colour that you like and were wearing that time when we saw yer man

We are always talking. And so we can forget that it takes a physical effort.

Every T is a flick of the tongue against the teeth. Every TH is a pressing together of the two so that air can be pushed through them; fluid-dynamically speaking, it’s exactly like letting water run through your cupped hands. Every F works the same way, but the teeth rest on the lower lip like you’re an American frat boy looking at a bum. [pullquote] What do you call this similarity? It could justifiably be called texture, boringly called quality, pretentiously called qualia, or druggily called flavour, harmony, or colour. Or we could look at them as places, and through that lens any act of speech is also a journey. [/pullquote]Each of these sounds is distinct, but created at the front of the mouth; after a while, they start to feel similar to one another in a way that the sounds made at the back of the mouth, the Ks and the Gs, aren’t.

Speaking Deutschland out loud, feeling the different parts of my mouth permute the positions they’re capable of, I feel a sense of wonder at this faculty we possess. So many squishy body parts have to perform as precisely as a Korean girl-band to make meanings by making sounds. And they do. Over and over. Isn’t that wonderful? I think so, and every time I speak the words of the Deutschland I think so all over again.