Riposte | Yayoi Kusama: From Here to Infinity

Each fortnight, HeadStuff brings an unadulterated critique of the global art scene. Click here for more.

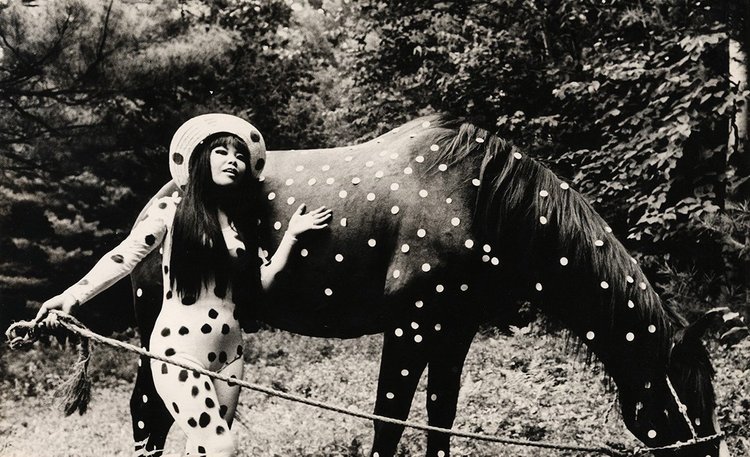

Yayoi Kusama is Japan’s – and quite possibly the world’s – most famous living artist. Born in Nagano, Japan in 1929, she moved to New York in the late 1950’s to pursue a career as an artist, and established herself as a vital part of the avant garde scene with painting, sculpture and performance works. She left New York for Tokyo in 1973, where, after taking up residence in a psychiatric facility in order to cope with her chronic mental health issues, she continued to create art and to show her work throughout Japan. In the last twenty-odd years, her work has garnered global attention, including major retrospectives, a constant slew of exhibitions and installations worldwide, and huge commercial success. She’s most well-known as the Princess – or, as she once ordained herself, the High Priestess – of Polka Dots. Intricate dotted patterns or “infinity nets” unify her body of work across mediums, from large dotted mushroom sculptures, to performance pieces with nude bodies covered in circles of coloured paint, to her contemporary “Infinity Mirror” installations, where countless LED light points are reflected into infinity on mirrored panelling.

This month sees the release of a children’s book about Kusama’s life and work,Yayoi Kusama: From Here to Infinity. Written by Sarah Suzuki and illustrated by Ellen Weinstein, the 26-page book describes the artist’s childhood in Japan, her early days in New York and her rise to global renown. Weinstein’s gorgeous, textured graphics accompanied by Suzuki’s airy narrative certainly make for a lovely book; but there are certain aspects of her life and career, namely her mental illness and her provocative early performances, that are conspicuously absent, ultimately deemed inappropriate for a book whose target audience is four- to eight-year-olds.

Yayoi Kusama: From Here to Infinity

How do you go about introducing concepts of sexual liberation, phallocentricity and mental illness into a book for children? I can support the decision not to get into her works involving nude performance, and to omit reference to the phallic implications of the “stuffed tubes” that appear in various sculpture works, as it does seem beyond the scope of a child under eight. But I query whether it isn’t a misrepresentation to produce a narrative about Kusama’s life and work without referencing her experience of mental illness, which she has repeatedly cited as the most significant influence on her artistic practice.

Kusama is outspoken about the significant link between her art and her psychological disorders. In a 1999 interview for BOMB Magazine she described her art as “a therapy for my disease”, and her obsession with mapping infinity nets in various forms stem from hallucinations that have plagued her since childhood. But in this sugarcoated children’s narrative, a creative outlet for chronic obsessive neurosis becomes a “devot[ion] to her dots”. What happens, one wonders, when a child finishes the book, and turns to the ever-more-accessible internet to learn more about Kusama? Even a cursory Google search will throw up articles and interviews which reference her experience of mental illness. Does the book’s avoidance of this subject not imply that it is something that should not be discussed? It may not be an easy topic to explain to a child, but failing to mention it at all here feeds into the stigma that persists in discourse surrounding mental illness in general.

It’s also pertinent to note how representation of Kusama’s identity as a female artist comes into play. Her use of colour and patterns lead some to dub her as an eccentric, a strain of rhetoric which can extend to a decidedly patronising, dismissive treatment of her work, such as Steven Heller’s piece in The Atlantic from 2012 in which he refers to her as an “orange-wigged living doll” and to her controversial performance works of the late ‘60s as “hijinx”. Suzuki’s text too participates in this narrative, making of her a fairy-like figure, with a paintbrush in lieu of a wand which she uses it to cover the world in dots.

The idea behind such a book as this is to provide an entry point for young children into a particular artist’s work; it must necessarily exclude layers of complexity which can be accumulated as a child matures. But is this sanitizing of Kusama, in a beautifully illustrated but highly selective telling of her life story, and a complete elision of her experience of mental illness, a stretch too far? The colourful “Princess of Polka Dots” is a palatable image, but it’s a rather partial one.