I want you to picture a simple Venn diagram. Just two little circles, no more, no less. In one circle, we have a neat little collection of the world’s most famous comedians. In the other, the nation of Ireland and the Irish people. And there in the overlapping space between the two circles, you’ll find all sorts of interesting stories – tales of our unexpected connections with some of the funniest people who ever lived. Of course, our own mischievous sense of humour is well-known by all. And we have certainly had our own fair share of stand-ups and comic actors. So perhaps it’s only natural that our finest cultural and political ambassadors have brushed shoulders with the most comical minds of the show business realm.

These performers are the modern pioneers who gave comedy its legitimacy from the dawn of the twentieth century to the present day. Each of them expressed themselves to their fullest capabilities – whether that meant delivering a finely-tuned monologue or falling backwards on their arses without breaking their necks. And if comedy is a low art, then so be it. Let us revel in its lowness. Let us celebrate the things it does best, the things no other artform can do. Throw down your banana peels, jot down your wittiest remarks, and prepare for the hecklers. Here are Ireland’s craziest comedy connections…

Big Jim Larkin and the Little Tramp

In November 1919 Irish union leader Jim Larkin was arrested in New York City on a charge of criminal anarchy. He had spent the previous few years promoting socialist causes in the United States and now found himself a target of the anti-communist establishment. Larkin was found guilty in a court of law and sentenced to serve between five and ten years in the infamous Sing Sing prison. It was there that he received an unexpected visit from a figure familiar to millions of people all across the world. The great public speaker suddenly found himself face to face with the most famous silent movie star of the day – Charlie Chaplin.

Chaplin had decided to join his friend Frank Harris on an impromptu visit to Sing Sing to meet the famous labour organiser. Under the watchful eyes of nearby guards the three men talked briefly about current affairs and about the poor conditions in the prison. However their conversation came to a quick end when Larkin politely insisted he receive no special treatment that his fellow prisoners would not be entitled to. Their meeting was over just as soon as it had begun but Larkin had left a meaningful impression on the comedian. Chaplin would even write about the encounter in his autobiography decades later.

Socialists like Larkin had a big influence on Chaplin’s politics and on the content of his films. The comedian’s film Modern Times (1936) told the story of a downtrodden worker in an industrial society. In one prophetic scene Chaplin’s character is mistaken as the leader of a Communist demonstration and arrested. In the 1940s and 1950s he would face similar political persecution himself, just as Larkin had before him. He was effectively exiled from America during the Red Scare amid the controversial HUAC hearings. He would not return there again until he was awarded an honorary Oscar in 1972.

In the meantime, Chaplin became a frequent visitor to Ireland. Between 1959 and 1971 the silent film star came to Waterville in Kerry with his family for a yearly holiday. Staying in the Butler Arms hotel, he enjoyed fishing on Lough Currane and walking the local beaches. But his love affair with Ireland would end in turmoil when The Troubles reached their height and the British born comedian began to fear for his safety. He would never return to Kerry again, dying six years later at home in Switzerland.

In 1998 a statue was unveiled in Waterville to commemorate the Hollywood icon’s special relationship to the town. A local film festival was also held yearly in his honour from 2011 onwards until the COVID-19 pandemic brought an end to the event in 2020.

George Carlin’s Irish Souvenir

George Carlin visited his ancestral homeland of Ireland in 1980. The controversial stand-up had always felt a strong connection to his Irish roots. He felt his love of rhetoric and language was genetic, pointing to his father’s success as a public speaker and his maternal grandfather’s love of Shakespeare. Plus, his mother had instilled in him from an early age a keen interest in all the great literature that the Irish people had produced.

Carlin had previously explored his Irish-Catholic upbringing to great comic effect on his record Class Clown (1972) – generating much controversy with his Seven Dirty Words routine, later the subject of a landmark Supreme Court obscenity trial.

As he travelled through Ireland for the first time, Carlin instinctively recognised the faces he saw. He felt at home with his tribe. Near the end of his trip, he travelled to the West of Ireland. Near the lakes of Killarney, he dug up a big clump of dirt to bring home with him. The comedian later planted the soil in his garden back in Los Angeles.

Slapstick x Absurdism

Long before he had his first Hollywood success, silent film star Buster Keaton spent his childhood touring the USA and performing with his parents in a family vaudeville act. Like a lot of comedians of the era, their routines were based around broad ethnic humour. Though not of Irish descent themselves, The Three Keatons would perform on stage as a rough-and-tumble Irish family. This particular brand of stage Irish was a common sight in early 20th century show business. Dressed up with a false beard and makeup, Buster Keaton would be tossed around the stage by his father in mock fights and arguments.

Acts like this came at a time when Catholic Irish were still considered second class citizens in parts of the country dominated by WASP elites. Such Paddywhackery reinforced negative stereotypes of Irish people as drunk and violent religious extremists. Naturally, it’s important to note that these stereotypes were much less harmful than those targeting African Americans, who faced incomparable systemic prejudice on a day-to-day basis.

Later in life, Keaton collaborated with Samuel Beckett on the playwright’s sole cinematic project, the aptly-titled Film (1965). Beckett had always populated his work with clown-like characters, like the bickering tramps in Waiting For Godot, or the title character in Krapp’s Last Tape, who at one point slips on a banana peel in an overt homage to classic slapstick comedy. Beckett was actually a fan of Keaton’s and he had previously offered him a role in the first American production of Godot but the film star had turned down that particular opportunity.

Film was an absurdist short with no real story, a mediation of sorts on the camera’s relationship to the human eye — an abstract examination of perception in all its forms. Beckett was satisfied with Keaton’s performance, though the comedian reportedly had some misgivings about the project. Indeed, critical reception to the film has been mixed since its initial release. And sadly, Keaton passed away just months after filming had finished.

The Quare Fellow and the Clown

Before making the leap to Broadway theatre and Hollywood films, the Marx Brothers toured the vaudeville circuits of the USA for decades. And like many of their contemporaries, they portrayed broad ethnic characters for humorous effect. By the time they reached the highest heights of international stardom, only Chico retained these characteristics with his fake Italian dialect and trademark wordplay. But did you know that his scene-partner Harpo originally played a wild drunken red-headed Irishman? Eventually, the comedian dropped this character in favour of his childlike silent pantomime trickster. Nevertheless, he continued to wear the red wig for the rest of his career, though it appeared blonde in the team’s black and white films.

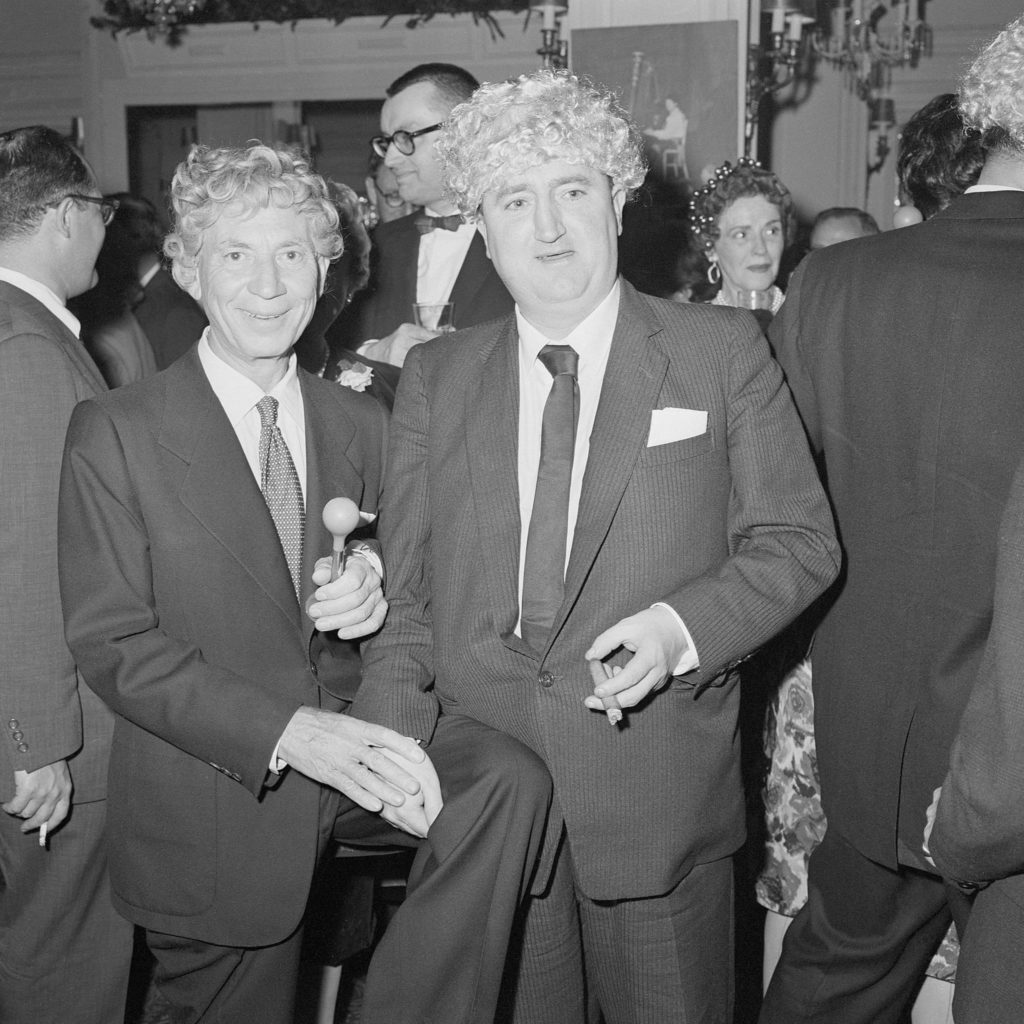

In something of a full circle moment, Harpo’s wig was later donned by none other than Brendan Behan – who dressed up and posed for the cameras right alongside the genuine article in a series of bizarre photos at the launch of the comedian’s autobiography in New York. These pictures can still be found online to this day.

An Invitation From Éamon de Valera

When Jack Benny appeared on David Frost’s chat show in the late nineteen-sixties, he pointed to his then-recent appearances in Dublin’s Gaiety Theatre as a highlight of his career. He was completely enamoured with the enthusiastic Irish audiences who gave him a fantastic reception. He recalled that when he returned to the Gresham Hotel on his final night in the city, there was a message waiting for him there inviting him to Áras an Uachtaráin on behalf of President Éamon de Valera.

Benny and his wife went straight away to meet the elderly politician. After fifteen minutes of polite conversation, de Valera’s telephone rang. He answered it and spoke a few words to the person on the other end of the line, then tried to hang up – but his bad eyesight prevented him from doing so. He fumbled with the phone for a moment or two before Benny finally intervened and helped to place it down in its cradle. De Valera thanked the comedian for his assistance and remarked that although he couldn’t see too well, he got along pretty well regardless. However, he also admitted that he often tripped and fell over a chair about once every four days, a fact that Benny found hilarious.

Laurel and Hardy’s Last Hurrah

Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy were travelling from New York across the Atlantic for a tour of the UK and Ireland in late 1953. Their stardom had waned in Hollywood since their heyday in the 1930s. Their final film Atoll K (1951) had been released to critical and commercial failure. The duo were now forced to return to performing live to support their wives and maintain their comfortable lifestyles.

Just the previous year, they had embarked on a similar tour and played the Gaiety theatre in Dublin and the Belfast Opera House. Now, as the SS America ocean liner entered Cobh harbour, Laurel and Hardy were surprised to find throngs of adoring Irish fans waiting for them there. Tears began to fill their eyes as the bells of Saint Colman’s Cathedral rang out to the melody of their theme tune, The Cuckoo’s Song. After they had docked and stepped onto dry land, the pair insisted on personally thanking the carillonneur in the bell tower.

Ultimately, Laurel and Hardy appeared for a month at the Olympia Theatre in Dublin. They stayed in nearby Dún Laoghaire in the beautiful Marine Hotel. The bar in the hotel would later be renamed in Hardy’s honour.

As an old man, Stan Laurel would fondly recall the reception he and his friend had received upon their arrival Cobh…

“Maybe people loved us and our pictures because we put so much love in them, I don’t know. I’ll never forget that day. Never.”