Mental Illness & The Secret Wish-Fulfilment of Crazy Ex-Girlfriend

“The situation’s a lot more nuanced than that.”

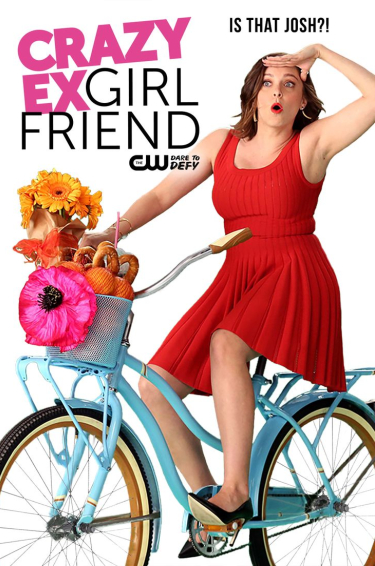

From the very beginning of Crazy Ex-Girlfriend in October 2015 we knew we were getting something different to the usual depiction of women scorned or abandoned; we sensed that it would be a tongue-in-cheek yet all-too-relatable account of how even the very smartest and most accomplished of women can believe that their chances at happiness are linked to the love of good men.

Men who label their ex-girlfriends “crazy” (often to their current girlfriends) are a familiar feature of real-life relationships. Part a way of dismissing their own role in a break-up and part a method of controlling future girlfriends’ behaviour, it’s a tactic so woven into contemporary culture that it’s employed not just deliberately by creeps but invoked unintentionally, unthinkingly, by well-intentioned men. Even one of the most beloved of rom-coms, 1989’s When Harry Met Sally, re-enforced a cliché that leads directly to the ‘crazy’ idea – the division of girlfriends into ‘high maintenance’ and ‘low maintenance’.

Crazy Ex-Girlfriend immediately drew attention to the way ‘crazy’ is used in these circumstances – as ‘high maintenance’, as ‘too much work’, as ‘too demanding/needy/emotional’ – by giving us a genuinely mentally-ill character in protagonist Rebecca Bunch, played with aplomb by show co-creator Rachel Bloom. In season 1 we learn that she has been medicated for anxiety and depression – even though her rejection of those pills might lead us to believe that she’s simply one of those over-stressed, over-worked individuals in a dark capitalist society who’s been persuaded to drug herself into a functional, even Aldous-Huxley-esque state rather than address deeper issues in her life. Her motivations for moving from the pressurised world of Manhattan to a small Californian town may be wobbly, but surely the act itself has the potential to ‘fix’ her and give her what she’s been looking for?

“I’m just a girl in love,” the second season theme song tells us, even though we know by now not to entirely trust it – the situation’s a lot more nuanced than that, we remember. We’re encouraged to focus on the ‘girlfriend’ part of the title, to pay attention to Rebecca’s relationships with sarcastic alcoholic Greg (who leaves early in the season) and teenage sweetheart Josh (who she’s set to marry by the end of the season). The season finale offers up a dark reprise of the song when we see a flashback to Rebecca in her early 20s, and realise that this is not the first time she’s been ‘a crazy ex-girlfriend’ – her law school professor broke her heart and prompted both an arson attempt and Rebecca’s institutionalisation.

By this stage, though, we know that the greatest love story is between Rebecca and her friends, an unlikely band of allies including her co-worker Paula, former romantic rival Valencia, and perpetual student Heather. The end of Season 2 sees a jilted Rebecca, still in her wedding dress, surrounded by these three strong women; early in Season 3 we witness these group of friends complain – in song – about men (acknowledging the gross generalisations they make as they go). And the theme song is about being ‘crazy’ – not so much about love at all.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lu3FE7BswYI

This is reinforced in the penultimate episode of 2017, ‘Josh Is Irrelevant’ (the last to include Josh’s name in the title). Josh – who on the one hand did little initially to invite Rebecca’s romantic interest and on the other did even less to explain why he left her at the altar – makes things about him, but Rebecca admits she’s hardly thought of him.

So, this is not a cute wish-fulfilment rom-com. This is not even about obsessive love and how ‘crazy’ women can get in relationships, or even at the prospect of one. It’s about what it means to be mentally ill and searching for a fix, a cure – something made painfully obvious in the optimistic song ‘Diagnosis’, in which the prospect of a label that will finally fit (and thus be something understandable and mean she’s not alone, not ‘broken’) appeals to, rather than scares, Rebecca.

But where the show does swoop towards cute wish-fulfilment territory it is how her friends and co-workers respond to Rebecca – someone who has not only insulted many of them personally but also caused them great stress with a suicide attempt. In an ideal world, of course, we would all respond this way – with kindness and empathy and swallowing down our own feelings and anxieties about whether or not that heat-of-the-moment outburst revealed a greater underlying truth.

“We are not easy to be around,” the late Sally Brampton acknowledges in her memoir of depression, Shoot The Damn Dog, one of the few memoirs to admit this unpalatable fact. Mental illness – like physical illness – can leave one cranky, unpleasant and difficult to be a good friend to. Undiagnosed mental illness – which is the case for Rebecca – increases the likelihood of it creating problems in interpersonal relationships; if you’re not sure what the problem is, how do you begin to (try to) fix it?

Every single one of Rebecca’s friends, regardless of what’s going on in their own lives, shows up for her. Valencia is the only one to ask for a promise that she’ll never attempt suicide again – a promise Rebecca knows, in a marvellously realistic move, she can’t make – but even then there is sorrow rather than rage. Compassion and worry rather than frustration and anger.

It is a lovely, lovely idea. It is also as much of a fantasy as the idea that moving to California will solve all of Rebecca’s problems, or that her romance with Josh could ever work out. The truth is that some people do not react with such grace and concern when someone in their life is in trouble, even as obviously as Rebecca is, post-suicide-attempt. Don’t we all have problems of our own, after all? And isn’t it selfish/attention-seeking etc? And even if there is worry in the moment, once the crisis has passed, life goes on.

There is a slight allusion to the intensity and possible unhealthiness of Paula’s half-mother, half-BFF relationship with Rebecca but aside from that it is to be expected that these three women – along with, adorably, the earnest Darryl who leaves a vacation early to make sure she’s okay – will take time off work and put the rest of their lives on hold in order to make sure that their friend is doing okay. Given that ‘fear of abandonment’ (whether grounded in realism or merely perceived) is among one of the criteria for Rebecca’s newfound diagnosis of Borderline Personality Disorder, and that her mother has been revealed as a manipulative (if well-meaning) fiend, it would be impossibly cruel to put her through more trauma at this time.

And yet more trauma does often come at this time for those dealing with mental illnesses, for those who are “not easy to be around” or to help. Not everyone will be sympathetic. Not everyone will understand. Some friendships, some romances, some relationships – they may fall apart under the strain of illness, of being a difficult person.

But who on earth needs to hear that when they’re looking to reach out for help? Who at their most vulnerable doesn’t need to believe in friends who will forgive angry outbursts prompted by internal panic and fear and maybe even ‘crazy’, who will understand and offer kindness and caring? Because the truth is that even if only one or two people can fulfil that role, it matters, and seeking help is always more constructive than swallowing down the feelings, the trauma, and waiting for it to destroy you.

It somehow seems a more ethical wish-fulfilment scenario than the standard rom-com we thought the show might be at first. Not so much that you will find Mr Right and he will solve all your problems, but that you will have friends who will care about you, no matter what.