Honour and Madness | The Bridge on the River Kwai Turns 60

For film goers of my vintage (mid 30’s), mention of Alec Guinness will conjure only one image, namely that of a cloaked, grey bearded old man known as Obi Wan Kenobi. For me (oddly enough, considering I am a Star Wars fan) any mention of Alec Guinness and I recall a much younger man, po-faced and skinny, dressed in Army khaki, namely Col. Nicholson from David Lean’s 1957 masterpiece The Bridge on the River Kwai. It isn’t a favouritism thing, it’s simply due to the fact that I saw The Bridge on the River Kwai before Star Wars. I think I was closer to 10 years old when I sat down one rainy Saturday afternoon to watch David Lean’s WWII epic. Although being over 2 and half hours long it held me in awe as I watched it that first time, and though this phrase is bandied about more often than it should be, I think it is safe to say on this occasion that it is one of the greatest (war) films ever made.

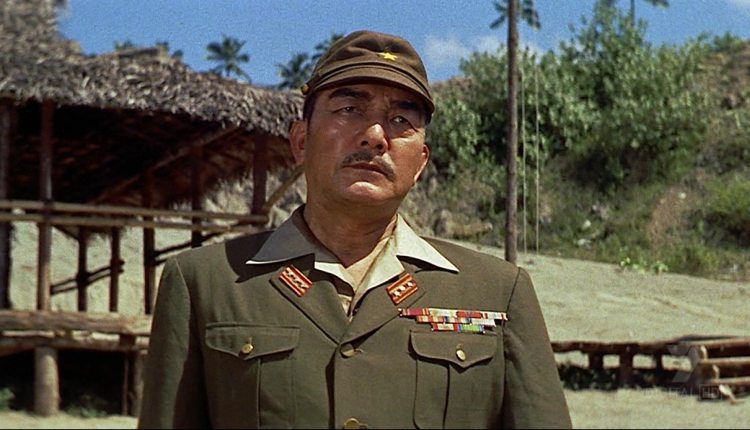

On this, its 60th birthday, The Bridge on the River Kwai has lost none of its majesty. It is as beautiful a film to watch today as it was in 1957, proudly boasting the Cinemascope format that was used to photograph the wilds of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) which stood in for the film’s actual setting of Burma. While the scenery and shooting are stunning, The Bridge on the River Kwai is held together by two fantastic central performances. Both William Holden as the American Major Shears (the box office draw of the film) and Jack Hawkins as the British Major Warden are both strong, but Alec Guinness as Col. Nicholson and Sessue Hayawaka as Col. Saito are flawless. Guinness went on to deservedly scoop the Best Actor Oscar for his performance and Sessue a nomination for Best Supporting Actor. Guinness’ stoic turn as the stiff upper lipped English officer is mesmerising, a career best, especially for those who may only be familiar with his legendary Ealing comedies or the already mentioned Star Wars films. Having carved out a niche for himself in those goofy comedy roles, to create such a visceral and strong character as Nicholson is astounding. His character is counterbalanced by the equally brilliant Col. Saito. Sessue Hayawaka, a star of the silent era who struggled to make the transition to talkies in the 1930’s, is remarkable in the role that he himself described as the greatest of his career, and it’s not hard to see why. Inept and cruel in equal measure, Saito realises that he needs Nicholson to get the bridge built and how he handles his pain, his struggle is absolutely absorbing.

Directed by David Lean, the undisputed master of the sweeping epic (Doctor Zhivago, Lawrence of Arabia, Great Expectations, Ryan’s Daughter, Passage to India), The Bridge on the River Kwai is built on a series of iconic moments and images, maybe none more powerful than the opening sequence. Birds of prey circle overhead as the railroad tracks, shot just above the angles of the bamboo crosses hammered into the soil by the track’s edge, stretch out in the distance, highlighting just how many died building the railroad. As Col. Saito prepares for the arrival of his latest batch of captured prisoners a strange sound is heard… whistling. Col. Nicholson, baton tucked neatly under one arm, marches his men into the camp whistling Col. Bogey’s March and carefully has his officers line up the men in ranks. Nicholson notices his men, some have boots, some have bare feet but still they march. This is a proud man, proud of his unflinching troops and he makes them march on the spot a little longer than necessary to show the assembled Japanese captors and Col. Saito that they are not for bowing.

This scene captures perfectly the attitude that Nicholson has towards his men, though he does verbalise it later in the film, “we are soldiers, not prisoners.” Col. Saito then highlights how completely opposite he is to Nicholson in telling the assembled men the contrary, that they are no longer soldiers, but prisoners. Saito intends to break these men and immediately Nicholson bristles. A standoff ensues between both when Saito insists that all officers must perform manual labour, something forbidden by the Geneva Convention. This is the crux of the film, the stumbling block that illustrates just how straight-laced Nicholson is, how dedicated he is to principle. He will not allow his officers work as manual labour on the construction of the bridge fording the river Kwai. The Japanese try to break him by locking him and his officers in the “oven”, a galvanised structure, 3 feet by 3 feet square, baking in the sun. Nicholson will not bend. Pulled out after several days, Nicholson is a shell of a man, pale and drawn and weak but one of the best sequences in the film, and surely something that swayed the Academy, was his hitch-stepped march from the oven to Col. Saito’s office. On the point of collapse, Nicholson holds his head up and meets his gaoler as an equal and not a sub-ordinate. Saito relents and Nicholson is heralded as a hero. What is amazing about this scene, as Nicholson is held aloft by his men for making their captors stand down, the final shot shows Col. Saito crying in his billet, banging his closed fists against his forehead. He has been shamed, he has brought dishonour upon himself. It is a heart breaking and telling moment, one that captures perfectly the Japanese concept of honour and one of those absorbing moments from one of the most talented actors of the silent era of film.

Honour is a massive part of The Bridge on the River Kwai. The Japanese must maintain their honour by having the bridge built and on time – Col. Saito is honour bound to commit hari-kari if it is not ready on time. The English must retain their honour by remaining soldiers and not prisoners, they must retain their dignity and must be seen as an example of ingenuity and endeavour. This sense of honour also ties in with the other key theme of the film – madness. The madness of war, the madness of Col.Nicholson and Col. Saito as they butt heads and the terrified madness of Major Shears as he returns to the prisoner camp to help destroy the bridge are some of the most prominent features in the film, so much so that the final word spoken in the film is “madness”, by Major Clipton as he watches the bridge be destroyed after the deaths of Nicholson, Saito, Major Shears and Lt. Joyce. Honour and duty drove both Nicholson and Saito to madness, Saito realising that his honour has been destroyed as Nicholson nails a wooden plaque to the bridge stating that it was built by the English, and Nicholson realising the folly of his ways in that amazing final scene. The look of shock in Nicholson’s face as a realisation dawns on him – he has built a bridge that will not stand as a monument to British endeavour but to the fact that they practically colluded with the enemy – is quite arresting. Nicholson only ever wanted his men to be the very best, to be an example to the Japanese of how a soldier should be. He threw them into the building of the bridge with gusto, showing the pluck and dint of the British soldier, to prove to their captors that they cannot and will not be broken. Nicholson was blinded by this, building a bridge that is far superior to anything the Japanese could have built themselves. It is only at the very end, as the bombing mission is on the verge of collapse that he realises his folly, a simple but stunning dawning, Guinness mining a deep vein of pathos; the horror in his eyes as he steps forward, pushing his cap back saying, “What have I done?” is heart breaking.

That final scene is a joy to behold, an example of how tension should be portrayed on screen (SPOILER ALERT – don’t read on if you haven’t seen the film). After a midnight mission to plant the charges at the base of the bridge Major Shears and Major Warden realise that the water level has dropped over night – the charges are visible. As the opening of the bridge looms closer, Nicholson takes one last walk along his creation and spies something amiss. He finds the explosives and traces the wires back along the river bed to the hiding Lt. Joyce, the young officer tasked with blowing up the bridge. All the while the chug of the train is heard in the distance growing louder as it draws closer and closer. The sounding of its shrill whistle cuts through the jungle, ratcheting up the tension. In a struggle with Joyce the young officer is killed and Nicholson tries to cut the cord, to stop the bombing as the remaining members of the bombing team try to stop him before he realises what he is doing. It is a truly amazing piece of filmmaking from one of the great masters of the art.

The Bridge on the River Kwai is David Lean’s masterpiece; while the films he made before and after it are stunning, Lawrence of Arabia in particular, none equal the power of this, his 1957 multi Oscar winning epic.