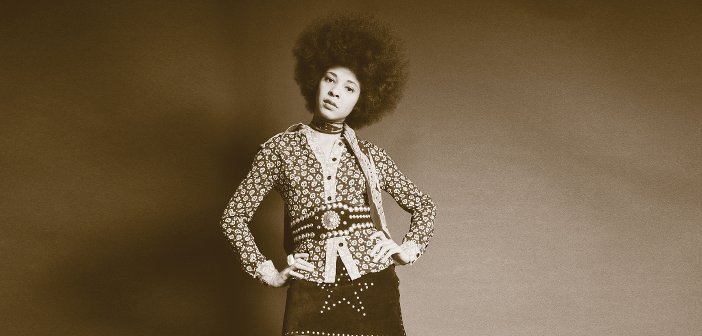

Ready, Willing & Able: Betty Davis’ Columbia Sessions

This planet wasn’t set for Betty Davis. It wasn’t ready in 1969, when she walked into Columbia’s 52nd Street Studios, New York with husband Miles to lay the funky foundations of both their future work. Maybe it’s never been ready. Connect the dots from James Brown’s jelly-hipped dynamism to purple deity Prince and you’ll draw a line straight through Betty’s compact discography. Her name is too often left out of the conversation.

Davis cut three albums in the ‘70s, plus a fourth that wouldn’t see release until 2009. It’s music as smoldering as the white-hot embers of a funk-rock bonfire. This was an artist who turned away Berry Gordy’s advances, and scoffed at Eric Clapton’s offer to produce her music, seeing Cream’s ace guitarist as too banal. Betty’s music wasn’t cut for the white room. It transported you to an acid-laced Technicolor alcazar of dizzying strobe lights and psychedelic drapes.

By the 1980s, though, Davis had left the music industry. Record buyers never took to her lust-charged wig outs. Maybe the sound of a woman wielding her own sexuality with two clenched fists was too decadent, too dangerous, even in the era of badass rock queens Labelle and Tina Turner. But her short career saw Davis start down a path later tread not just by Prince, but Rick James, Erykah Badu, Outkast, Missy Elliott and a dozen other hard-nosed artists who’ve pioneered their own brand of diamond-edged freak-outs.

Before all that solo stardust, there was Betty Mabry, a promising and respected young singer who grew up in Pennsylvania and North Carolina before making her way through the countercultures of NYC’s Greenwich Village as a model, DJ and songwriter for hire. In ’68, she married Miles Davis, a visionary trumpeter who at 42 years of age was already one of the greatest jazz musicians to ever put his mouth to a trumpet.

Before all that solo stardust, there was Betty Mabry, a promising and respected young singer who grew up in Pennsylvania and North Carolina before making her way through the countercultures of NYC’s Greenwich Village as a model, DJ and songwriter for hire. In ’68, she married Miles Davis, a visionary trumpeter who at 42 years of age was already one of the greatest jazz musicians to ever put his mouth to a trumpet.

Miles was determined to make his 23-year-old wife a star. In turn, Betty left her handprints all over his subsequent output. Her image is draped across the cover of 1968 album Filles de Kilimanjaro, which included the tender tribute ‘Mademoiselle Mabry (Miss Mabry)’. Betty introduced her husband to sounds of Sly Stone and Jimi Hendrix. His taste in fashion went from dapper jazz club formal to more colourful, glitzy gear. And her carnal style inspired his crucial 1970 electric-swathed jazz album Bitches Brew. “The marriage only lasted about a year,” Miles would write in his autobiography years later, “but that year was full of new things and surprises and helped point the way I was to go, both in my music and, in some ways, my lifestyle.”

The coming together of Betty and Miles altered musical history forever. It skewed us into an alternate reality of rock and jazz fusions and lecherous funk struts. The proof is in their post-nuptials output. But for almost half a century, a key piece of evidence has been missing. The couple’s sessions at Columbia Studios have been among the most sought-after lost recordings in history – the stuff of rock‘n’roll folklore. Well, those tapes have finally been unearthed and, with Betty’s approval, released as The Columbia Years 1968-1969. Turns out, we should have been believers all along.

A seasoned studio vet, Miles structured the sessions in advance. His impossibly gruff voice weaves in an out of the recordings, directing proceedings from behind the boards. The couple’s sway helped assemble a group of musicians that included Harvey Brooks, Billy Cox of Band of Gypsys, Herbie Hancock and Mitch Mitchell of The Jimi Hendrix Experience. But this was Betty’s platform, and she was low-key calling the plays.

A seasoned studio vet, Miles structured the sessions in advance. His impossibly gruff voice weaves in an out of the recordings, directing proceedings from behind the boards. The couple’s sway helped assemble a group of musicians that included Harvey Brooks, Billy Cox of Band of Gypsys, Herbie Hancock and Mitch Mitchell of The Jimi Hendrix Experience. But this was Betty’s platform, and she was low-key calling the plays.

“She ran the session through Miles,” said bass player Brooks in a new interview included in the release’s liner notes. “I don’t think she was comfortable enough to walk out on the floor and just really take control. Which, you know, very few… you really gotta be an established artist to do that. But she was very present.”

The Columbia Years are demos, not meant to sit side-by-side with Davis’ immovable discography. But that doesn’t mean the tracks don’t knock hard. The rickety guitars and organ on ‘I’m Ready, Willing & Able’ provide the backdrop to an early declaration of Betty’s sexually-saturated swank. Snappy block party jam ‘Hangin’ Out’ and sweet ballad ‘Live, Love, Learn’ hint at the pop star she would later suppress.

Elsewhere, the sneering cover of Cream’s ‘Politician’ (renamed ‘Politician Man’) doesn’t quite smash the pavement with the same force as, say, 1973’s ‘If I’m In Luck I Might Get Picked’, but you can hear the inception of a frontwoman who could snatch the life right out of you.

Betty would ultimately nail down her sound away from of her husband’s gaze. During a session for ‘Politician Man’, she is said to have sneered “Get in the backseat” – a declaration of artistic liberation. The marriage was over after just a year, but the line tugged at Miles’ heels for over a decade. The obsession eventually surfaced as song ‘Back Seat Betty’ from 1981 album The Man With The Horn.

[youtube id=”eMw16adjL8k”]

“After my marriage to Miles broke up, I was living in California, and I received a call at about four o’clock in the morning and this song just started playing,” revealed Betty in a rare interview, also included in the liner notes. “And I said, ‘This has to be Miles…’ And he got on the phone and he says, ‘I’m namin’ that song ‘Back Seat Betty’.’ And it came from my saying, ‘Get in the backseat’ on ‘Politician’. It really affected him, you know what I mean?”

Miles was a genius, but he wasn’t a nice dude. He is believed to have a brutal propensity for violence against women, and his attitude to Betty seemed far from healthy, going as far as tossing the Columbia recordings to stifle his young wife’s ambitions.

“He told me later on that if he would’ve had them release my music, he was afraid I’d become a big star and leave him,” Betty said. “Now those were his exact words. So he stopped it. He just thought I would leave him if I became famous. But I never needed his fame. I was just married to him, as his wife. I was shocked that he would think that. I thought he knew me better than that. I wasn’t interested in becoming famous. That was Miles.”

Miles Davis died in 1991, his legacy long-cemented thanks, in part, to the revolutionary Bitches Brew. Even those who couldn’t separate a trumpet from any other piece of brass know the name to be that of a musical grandmaster.

Betty’s seventies albums became iconic to the skeezers and weirdos who worshipped at her altar. 2007 reissues of her catalogue drafted in a new generation of fans, and now we have The Columbia Years to complete the historical text. It’s the sound of a young renegade’s genesis. The origin story that blossomed into one of funk’s most scintillating chronicles.

Photos by Baron Wolman and courtesy of Iconic Images via Light In The Attic Records

[youtube id=”fxKBnR_8LIM”]