Wallada bint al-Mustakfi, Poetic Princess

Wallada was born in 1001, the daughter of a noble in the Andalusian city of Córdoba. In 711 an army of Moors coming up from Africa had conquered the city for the Umayyad Caliphate, along with most of modern Spain. Córdoba became the capital of this province on the edge of their empire. Fifty years later, after the Umayyads had been deposed, a prince of their line named Abd al-Rahman fled to Córdoba. Several of the locals had taken advantage of the chaos to declare independence, and he conquered them and welded them together into the independent Emirate of Córdoba. By the time Wallada was born his descendents had declared themselves Caliphs, [1] and Córdoba was a city of half a million people – one of the most advanced cities in Europe.

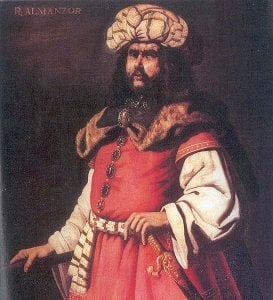

Unfortunately for the Córdobans, however, by this time the Umayyads had definitely begun to lose their grip on their caliphate. In 976 a ten year old boy named Hisham had succeeded to the throne. In the grand tradition of child rulers throughout history, fierce competition immediately started over the regency (and thus effective control of the caliphate). The eventual winner in this was al-Mansur Ibn Abi Amir, a powerful leader whose victories against the Christian kingdoms clinging to the northern part of Spain earned him infamy as “Almanzor”. He died in 1002, with his son succeeding to the regency.

Sadly the son was not the equal of the father, and Wallada grew up in a city rocked by civil strife. In the sixteen years after Hisham’s death in 1008, a dozen men ruled Córdoba. In December of 1023, a cousin of her father named Abd ar-Rahman was declared Caliph. A month later her father led the mob that murdered the new caliph, and declared himself Caliph Muhammed III. Suddenly Wallada was a princess. Her father was not very popular, however, and a year later he was forced to abdicate and leave the city. Wallada inherited his house, and his fortune.

Though Wallada was (through her father) a direct descendant of Abd al-Rahman, she would not have fit any stereotypical idea of a “Moorish princess”. In fact, the rulers’ habit of populating their harems with local women and slaves meant that the royal family were perhaps the least “Moorish” of anyone in the city. Wallada was noted for her fair skin, blue eyes and blonde (or possibly red) hair – beauty she became notorious for, as she was famous for going out in public without a veil, and for wearing the more revealing transparent fabrics that were popular in Arabia at the time. Traditionally this is supposed to have led to condemnation from the more conservative Córdoban religious scholars, though the city’s tradition of religious freedom meant that they could not force her to conform. In defiance of them, Wallada is said to have had her verses embroidered on her tunic. Translations vary, but one is:

I am fit for high positions by God and am going my way with pride.

I allow my lover to touch my cheek and bestow my kiss on him who craves it.

Poetry was a hugely important part of Córdoban culture at the time, and members of the upper classes were expected to be able to express themselves in verse. With her wealth, Wallada set up a poetry school for women in her father’s house. Her free teachings helped many from the middle classes to elevate themselves, and made her very popular in the city. She also competed in the city’s poetry competitions against male poets, where they would each provide an ending to an unfinished poem. The one whose poetry was judged the better fit was declared the winner. It was at these competitions that she met Ibn Zaydun.

Between you and me (if you wished) there could exist

What cannot be lost: a secret undivulged

– “To Wallada”, by Ibn Zaydun.

Abu al-Waleed Ahmad Ibn Zaydun was, like Wallada, a member of the noble classes. His family had been political opponents of hers. It’s unclear when the two began their affair, though it seems to have been after 1031. That was the year the Caliphate of Córdoba finally collapsed, breaking apart into several smaller independent principalities (known as taifas). The last caliph fled the city, and rulership of the taifa of Córdoba fell to the leader of the city’s most powerful family – Abu ‘l Hazm of the Banu Jawahr. Abu ‘l Hazm established a Roman-style republic (though he was still the “Custodian” of the city), with a council of ministers (called wazirs) to advise him. A court like that gives a smart young man plenty of room for advancement, and Ibn Zaydun was just such a man.

In the eyes of the people, then, Wallada represented the glories of the past while Ibn Zaydun was the face of the future. Their romance was scandalous, and at first they tried to keep it hidden. They wrote each other poems of passion, though they lamented their need to be circumspect. Wallada wrote:

How can I bear this being cut off from you, alone?

Yes, Fate did hasten what I had been afraid of!

Time passes, yet I see no end to your long absence,

Nor does patience free me from the bondage of yearning!

The two wrote poems back and forth, and the entire court was soon buzzing with gossip about the affair between the dashing young wazir and the beautiful princess. And then, it all began to go sour. Quite what it was that drove them apart is impossible to say. Some point to Ibn Zaydun’s criticism of her poetry, which he would include in his poems to her. Another cause often given is that Wallada found Ibn Zaydun making love to one of her slaves, an African girl. It is this that gave rise to one of her most famous poems, rebuking him:

If you did justice to our love, you would not desire nor prefer my slave girl.

Nor would you forsake a fertile branch, in its beauty, and turn to a branch devoid of fruit.You know that I am the Moon in the sky, but burn, to my chagrin, for Jupiter. [3]

Ibn Zaydun wrote back in response:

You compelled me to commit the sin which I had committed,

You were right, but pardon me, oh sinner!

Needless to say, Wallada was less than impressed by this non-apology. Ibn Zaydun’s other appeals (in which he declares that he has remained faithful, though she did not deserve it) were equally ineffective. Into this breach between the two stepped Ibn Abdus, another one of the ruler’s wazirs. Little is known of him outside of his history with the two, but we know that he was in love with Wallada, and jealous of Ibn Zaydun. In fact, some stories even have it that he contrived to ensure that Wallada would catch Ibn Zaydun with the African slave. In any case he was quick to make his move. Ibn Zaydun was quick to take umbrage at how Wallada had moved on. He wrote a poem and sent it to Ibn Abdus:

You were for me nothing but a sweetmeat that I took a bite of and then tossed away the crust, leaving it to be gnawed on by a rat.

The rat, of course, was Ibn Abdus. Popular legend gives him a rat-like appearance, to make the satire bite deeper. He was able to turn this verse back on Ibn Zaydun, by making it known that he had referred to the popular princess Wallada as a crust. Wallada herself was enraged by the verse, and turned the full force of her ire upon Ibn Zaydun. There were rumours that he had homosexual relationships, though whether this would have been a crime in Córdoba at the time is unclear. In fact, Wallada herself has been rumoured to have had a relationship with one of her pupils, a girl named Muhya bint al-Tayani. [2] Still, Wallada made it clear that in her opinion the reason why Ibn Zaydun had abandoned her was because of his preference for his own gender. The most erudite of her poems attacking him is:

Because of his love for the rods in the trousers, Ibn Zaydun,

In spite of his excellence,

If he would see a penis in a palm tree,

He would turn into a woodpecker. [4]

The feud between the two ended when Ibn Zaydun was imprisoned by Córdoba’s ruler, and then exiled. Whether this was because of Ibn Abdus, or because of Wallada’s accusations, or because of his own failed political machinations, is unclear. He moved to Seville, a taifa which had been one of the first to declare its independence from the Caliphate. There he wrote the poetry for which he is truly remembered – the poetry in which he laments the loss of his city, and the loss of his princess, in terms that often blur the lines between the two.

With passion from this place

I remember you.

Horizon clear, limpidThe face of earth, and wind,

Come twilight, desists,

A tenderness sweeps meWhen I see the silver.

Coiling waterways

Like necklaces detachedFrom throats. Delicious those

Days we spent while fate

Slept. There was peace, I mean,And us, thieves of pleasure.

Now only flowers

With frost bent stems I see.

In 1070 Córdoba fell under the control of Seville, and Ibn Zaydun was able to return briefly to the city of his youth. He was sixty-seven, and Wallada was sixty-nine, and their youthful passions had cooled. Legend has it that they were reconciled, before he left the city once more. He died in Seville the following year. Wallada lived for another twenty years, continuing to run her school until she died in 1091 – the same year that Córdoba was conquered by invaders from far-off Marrakesh. City and princess, they fell the same day.

Wallada’s poetry found little favour in the centuries after her death. Both Catholic and Islamic scholars had little time for a woman so assertive, and so unwilling to show proper virtue. In fact, it is only thanks to her role as Ibn Zaydun’s muse that any of her works survives – eight of the nine poem she wrote that we have were addressed to him, whether in love or in hate. The pair remain a proud legend of modern Cordova – the fiery passion of their poems expressing the Spanish ideals of romance. In 1971 a monument was erected to them – the “Monument of the Lovers”. A poem by each decorate the sides, while on top two hands reach out – touching, but not quite able to grasp. Doubtless there was more to the Princess of Córdoba than this one romance – in her ninety year life as an independent woman in a male-dominated society, so many tales must be untold. All we have is a narrow window, but what we see through that is magnificent.

Images via wikimedia except where stated.

[1] An Emir is a purely earthly ruler like a king. A Caliph is also laying claim to religious authority.

[2] Sadly few of Muhya’s poems seem to have survived – possibly due to their reportedly lurid content. This is a shame, as she is reported to have been Wallada’s greatest student.

[3] “Jupiter” here is a pun, as the Arabic name for the planet (“al-Mus?h?tar?”) is the same as “to buy”. Wallada is using it to refer to “someone that she bought”, a slave. (Thanks to commentator Greta for pointing that pun out to me.)

[4] The “penis in a palm tree” is less random than it might seem. A popular book at the time in Córdoba was Ibn Sina’s Hayy ibn Yaqzan, which contained a description of the popular sailors fantasy of the magical Island of al-Waqwaq. On this misogynistic utopia, naked women grew on trees like fruit and could be cut down by sailors who could then have sex with them. The island was named for the cries of these unfortunate women-fruits who could only exclaim “waqwaq” (the Persian for “help”) before they died. Wallada’s commandeering of this dehumanizing image of consumable femininity is counterpointed by her deliberately depriving Ibn Zaydun of his humanity, by turning him into a woodpecker.